Arnold von Harff’s travelogue travels to Oxford

by Aysha Strachan

The year is 1813. The Bodleian library acquires what is later to be known as MS Bodley 972 as part of a collection of late medieval travelogues which tell of the encounters of knights on their pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

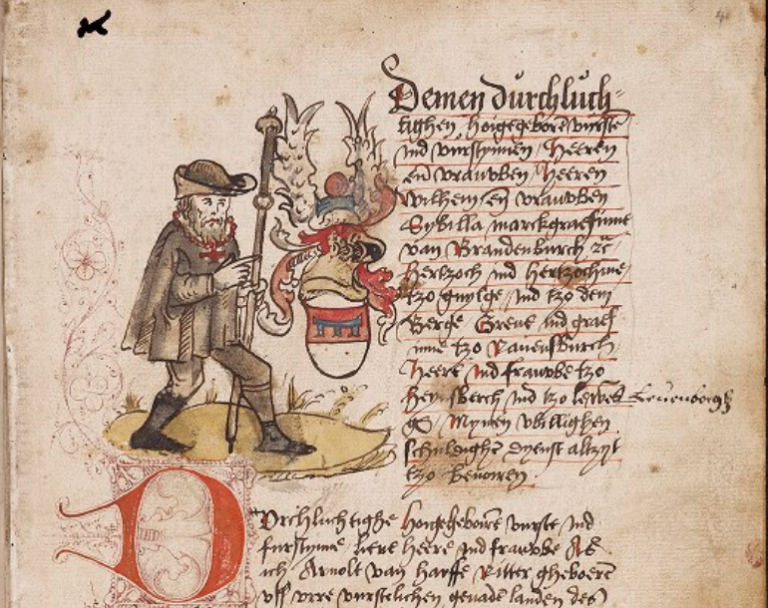

One of the most heavily illuminated of this collection is the Reisebericht (c.1554) of the knight, Arnold von Harff. The travelogue consists of Arnold’s tales of his pilgrimage to the Holy Land between the years 1496-1499. Within its 167 pages are 46 drawings, 11 of which depict a range of curious beasts (some of which we might think of as fantastical these days, but which were very real in the late medieval imagination). The illuminations take the form of pen-and-wash drawings, executed in a relatively cheap brown ink and quickly coloured with broad brush strokes. Hand-drawn images are nevertheless a nice touch in a manuscript composed some 118 years after printing began. The illuminator seems to have devoted all their care and attention to the Harff family crest, suggesting that family pride was of the utmost importance.

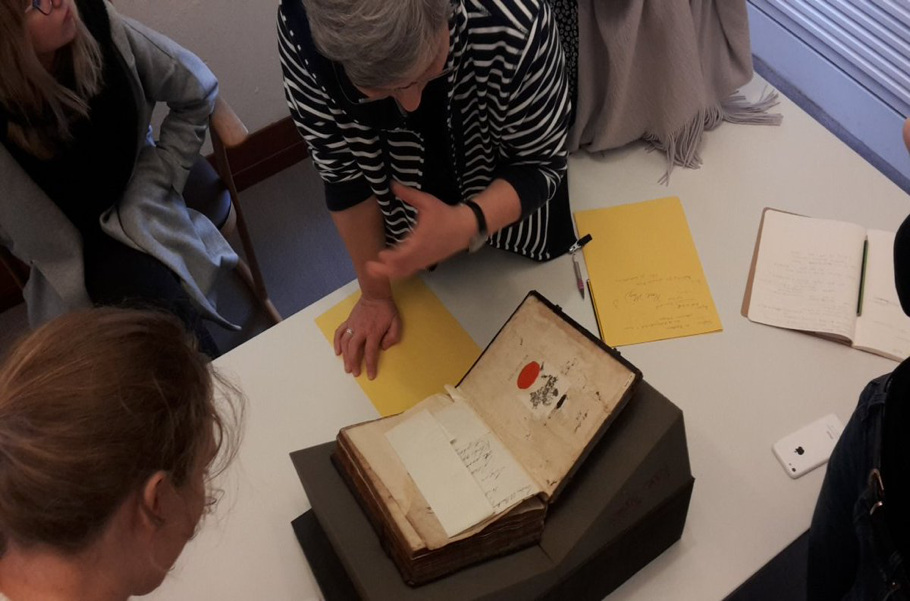

As I sit in the Weston Library in Hilary Term 2019, I open Arnold von Harff’s Reisebericht [travelogue] for the first time as part of the Palaeography, History of the Book, and Digital Humanities method option for the Master of Studies in Modern Languages.

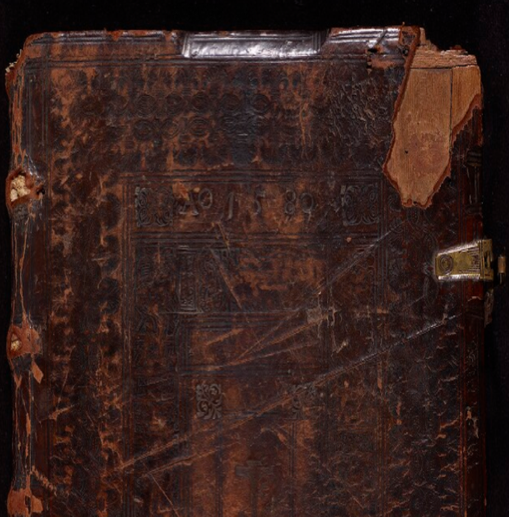

I carefully open the dark brown leather binding of the wooden boards, sealed by two ornamental metal clasps. The use of metal clasps for practical purposes is a trend which died out in the 16th and 17th centuries for all but ornamental value. It becomes clear that I am dealing with a precious collector’s item: an ornamental book that you would want to pass down the family.

Keeping it in the family

The first language I encounter is the very same Ripuarian dialect from the area in which the travelogue was written: the border region between Westphalia and the Netherlands; (Ripuarian is a low-Franconian dialect found in the West German Rhineland and gets its name from ripa: the Latin for riverbank).

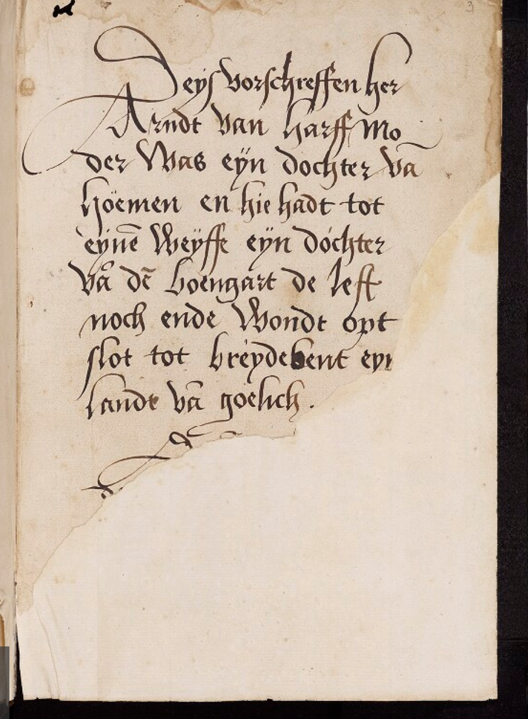

There is a flyleaf written in this Ripuarian dialect (fol. 3r) which tells of the mother of Arnold von Harff and her marriage history in a handwriting which is roughly contemporary with the manuscript. Peter Jorgensen identifies that the inscription is identical with the Munich manuscript of Arnold von Harff’s Reisebericht (München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, CGm 2213/32), only ours is written in a larger hand. It is therefore highly likely that the scribe of MS Bodley 972 has copied another manuscript.

Deys vorschreffen Her Arndt van Harff moder was eyn dochter von höemen en hie hadt tot eyne weyffe eyn dochter van dem boengart de left noch ende wondt opt slot tot Breydebent eyn landt von goelich.

[The aforementioned Lord Arnold von Harff’s mother was a daughter of the Höemen family, and he had a wife of the Von dem Bongart family who is still alive and resides in Breitenbenden castle.]

The castle could well be Schloss Eicks or Burg Satzvey, situated in Mechernich in the Rhein-Erft region which borders the Netherlands. Castle location aside, I find myself asking why this marital information was considered so important that it should find its way into the manuscript pastedown.

As it turns out, in 1675, Johann Wilhelm Mirbach was to become the new owner of the Harff family castle, having married Johann Damian von Harff’s sister, Maria Barbara. Family lineage, inheritance and marriage politics play a huge part in the Harff family, so it is fascinating to see this reflected in the details of the flyleaf: with the patriarchal line dying out, I am not surprised that the family were desperately asserting their lineage in the pages of this manuscript. The insistence on the long lineage of the Harff family supports the claim that the family wished to keep hold of as many manuscript editions as possible and that the family are proud to provide evidence of Arnold von Harff’s noble lineage- something Arnold does not stop mentioning in his account.

Alas, this travelogue did not stay in the von Harff family forever. I soon find myself on a wild-goose chase, hunting down the provenance of MS Bodley 972: who ended up owning this manuscript last before it came to Oxford?

Putting your own stamp on the binding

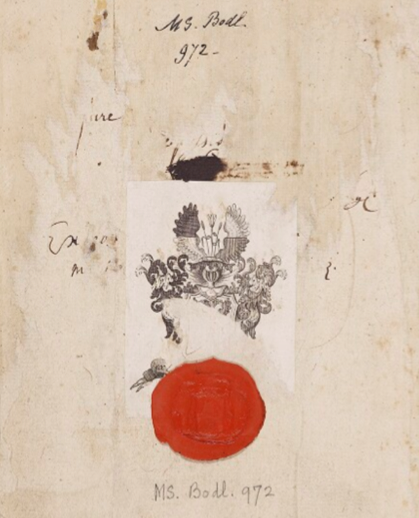

To help identify changes in provenance, I first turn to the inscription on the binding: ‘Ao 1580” and the scratched-away crest, replaced with a red seal on the inside upper board:

You can see a series of deep scratches and cuts that have penetrated the leather and in the top right-hand corner of the front cover; there has been a visible attempt at removing the leather from the wooden boards- a possible attempt to remove the binding entirely with an intention of a new binding. It is as though with each new provenance, the latest owner fights to have the final say: ‘this book belongs to me now’.

The exlibris on the inner front cover belongs to the book collector to a Mr F. W. Van Klipping, who has also written a beautiful poem on the final folio, but a considerable effort has been made by the next owner to erase the Klipping’s exlibris by using a red seal. It is possible that this example of a seal marks a new trend in exlibris, in erasing the previous provenance with a view towards quite literally ‘putting one’s own stamp’ on the book. But who might this seal belong to?

Tracing provenance: who is the mysterious Karl Etter?

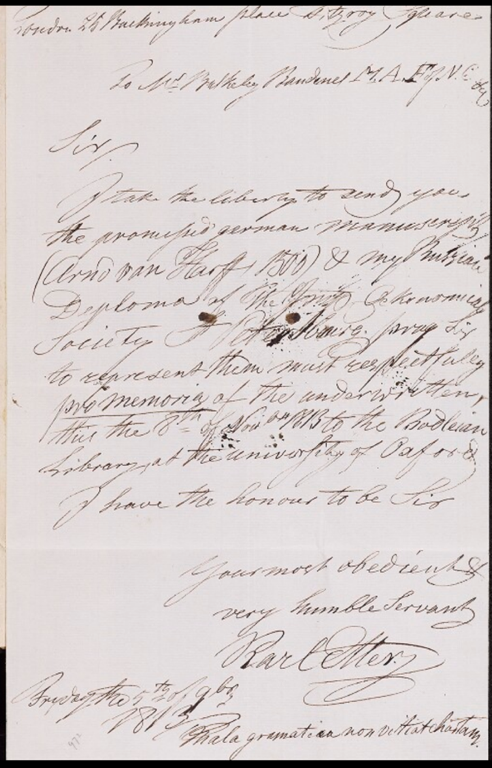

It is possible that the red seal which erases Klipping’s exlibris belongs to Mr. Karl Etter who has included a letter bestowing the book to the Bodleian library in 1813:

London, 25 Buckingham Place, Fitzroy Square

To Mr Bulkeley Bandinel, MA. F. of N C (Fellow of New College)

Sir,

I have the liberty to send you the promised German manuscript (Arnold von Harff, 1500) and my Russian Diploma of the Royal Economical Society St Petersburg proud to represent them most respectfully pro memoria of the underwritten, this the 8th of November 1813 to the Bodleian Library of the University of Oxford. I have the honour to be Sir Your most obedient and very humble servant Karl Etter

Friday the 8th November 1813

mala gramatica non vitiat chartam [bad grammar does not vitiate the deed]

I enjoy Etter’s Latin motto here: clearly a scientist, he must have been especially keen to assert his status as a learned man and scholar of repute when addressing the Oxford librarian. Nobody has yet traced a Mr Karl Etter from his letter connecting him to MS Bodley 971; the internet fails to provide much – if any – information on him, besides his involvement in the in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and his diploma is lost to the void.

In a newsletter from the year 1816, I discover news of Etter’s research into mineral composites from an annual of scientific breakthroughs. Finally, I find out that he also goes by the anglicised name of Charles Etter. He collected many curious items such as a Chinese goddess statue, of which he has produced his own drawing under which he self-declares as: Caroli Etteri mineralogi e antiquarii petropoli [Karl Etter, mineralogist and antiquarian of St Petersburg]. Etter eventually sent his drawing of the goddess and a Chinese dragon statue to Göttingen via Ritter von Struve. On this drawing we can see Etter’s signature and stamp; despite the monochrome reproduction, it is clearly a very similar – if not identical – seal to the red one we see on the inner board of MS Bodley 972.

St Petersburg societies must have been the ideal location to discuss, buy and exchange curious collectables such as our manuscript. This is just the kind of place where Etter might have come into contact with book collectors of illuminated travel manuscripts. Etter’s letter implies that he had met Bodley’s librarian and had spoken about his exciting manuscript acquisition.

The same year the Reisebericht makes its pilgrimage to Oxford, the Bodleian’s former under-librarian, Mr.Bulkeley Bandinel, takes over the position of chief librarian. The decision to address Mr Bandinel was no coincidence: he was given a grant in 1811 with which to purchase foreign manuscripts such as William Wey’s travelogue, MS Bodl. 565, and was renowned for his interest in pilgrim travelogues. The quality of his repairs to manuscripts is somewhat dubious and Bandinel has not gone down in history for his care with manuscripts; (in his edition of Wey’s Itineraries, through an insufficently careful attempt to correct the binding error in MS Bodl. 565, Bandinel does not clarify matters, but instead increases the state of disorder).

Before sending it to Oxford, it seems that Etter went to great lengths to fix some frailer parts of the manuscript. Convinced that Etter did more than merely affix a letter to the manuscript, I discover that he reinforced the torn genealogical account (fol. 3r), which can be deduced from the Britannia watermark that is consistent with his letter to the Bodleian and the pages that follow to make up the quire (fols. 1r-2v). This Britannia watermark was common for paper mills in London c.1800; I trace the nearest paper-seller to Etter’s London address that could have been a possible match. Coincidentally, the paper seller Nathaniel Rogers Hewitt’s paper business was based on the same road as Etter’s London residence, in Fitzroy Square.

All thanks to Karl Etter entrusting Arnold’s Reisebericht to Bandinel’s care at the Bodleian, I have been able to study its pages. At this point, I feel like Sherlock Holmes: I have tracked down the mysterious Karl Etter and solved his involvement in the mystery of the MS Bodley 972 provenance.

Aysha Strachan

King’s College London

Aysha is a PhD student in German at King’s College London/Humboldt University Berlin supervised by Sarah Bowden and Andreas Krass and funded by the LAHP. She completed the MSt. at Oriel College, Oxford in 2019 and took the History of the Book method option to compliment her research into the depiction of transgressive women across diverse medieval genres.

Selected Bibliography

Bulkeley Bandinel, ed. The Itineraries of William Wey, Fellow of Eton College. To Jerusalem, A.D. 1458 and A.D. 1462; and to Saint James of Compostella, A.D. 1456. From the original manuscript in the Bodleian library. Printed for the Roxburghe club, London: J.B. Nichols and sons, 1857).

Click here for Mary Boyle’s most recent blog post for Oxford Medieval Studies: Arnold von Harff: Knight, Pilgrim, Guide, and Author. 22-04-2021.

Malcolm Letts ed., trans., The Pilgrimage of Arnold von Harff, Knight from Cologne. Through Italy, Syria, Egypt, Arabia, Ethiopia, Nubia, Palestine, Turkey, France, and Spain, which he Accomplished in the years 1496-1499. Works issued by the Hakluyt Society, 2nd series, 94, electronic reproduction (Surrey: Ashgate, 2010).

Otto Pächt, Jonathan J. G. Alexander, ‘Entry no. 190: Bodley 972 (28066) 1554’, Illuminated Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, Vol. 1, German, Dutch, Flemish, French and Spanish schools. Oxford. (1966).

Peter A. Jorgensen, Die Bodleian Handschrift der Reisebeschreibung des Ritters Arnold von Harff, in: Rheinische Vierteljahresblätter 52 (1988), S. 221-225.

Peter Jorgensen, Barbara M. Ferré, ‘Die handschriftlichen Verhältnisse der spätmittelalterlichen Pilgerfahrt des Arnold von Harff‘, Zeitschrift für deutsche Philologie cx (1991).

Volker Honemann, ‘Zur Überliefung der Reisebeschriebung Arnold von Harff‘, Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur cvii:ii, (1978).

Eberhard von Groote, ed. Die Pilgerfahrt des Ritters Arnold von Harff von Cöln durch Italien, Syrien, Aegypten, Arabien, Aethiopien, Nubien, Palästina, die Türkei, Frankreich und Spanien wie er sie in den Jarhren 1496 bis 1499 vollendet, beschrieben und durch Zeichnungen erläutert hat. Nach den ältesten Handschriften und mit deren 47 Bildern in Holzschnitt. (Cologne: J. M. Herbele, 1860).

Image Permissions

Digital Bodleian (images from MS Bodl. 972: Creative Commons non-commercial license, with attribution (CC-BY-NC 4.0). Images © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

Wikimedia Commons (Photograph of Bulkeley Bandinel, died 1861, Bodley’s Librarian): Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-SA 3.0). Unknown photographer.

Other images kindly reproduced with permission from Henrike Lähnemann.

1 thought on “From the Holy Land to the Bodleian”