Oxford, more than many other cities, is like a game. To merely observe is fascinating. As an Oxford intern you will get the chance to play a little yourself. You won’t have to know all the rules and moves since there’ll be lots of kind players to help you and time to learn as you go. So, here are just a few suggestions and basic rules for the future Oxford intern. To compile them, I have drawn on my own experiences during my internship with Henrike Lähnemann in Trinity term 2024.

By Philip Flacke

1 Read (oh, and watch TV)

To visit Oxford without reading is like going to the movies with a pair of diving goggles on – possibly enjoyable but bringing with it the danger of looking a little foolish and the certainty of missing out part of the fun. For the Oxford intern, this might include preparation for whatever it is they will be doing. In my case I had to read up on Homer, the Nibelungenlied, Hans Sachs and Franz Kafka, which already gave me an impression of what a wonderful place I would go to: a town where in just under three months you could engage yourself with writers and texts as far apart as these and bring them together in meaningful ways.

It may say something about the manner of going about these things in Oxford that anecdotes proved to be among the most fruitful results of this preparatory reading: The German philologist Karl Lachmann, who translated a passage of the Iliad in Middle High German Nibelungenstrophen, prompting in turn the classicist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff to translate a passage of the Nibelungenlied in Greek hexameter. Or Kafka, who together with his classmates cheated in his Greek exam. There is an Oxford counterpart to Kafka not knowing his Greek. Allegedly, the philhellene and Oxonian Oscar Wilde wouldn’t stop translating from the Passion of Christ in his viva voce examination for ‘Divvers’ even after being told it was enough, replying: ‘Oh, do let me go on. I want to see how it ends.’

Even more than other cities, Oxford is an intertextual place. The streets, parks, colleges and libraries resonate with stories and anecdotes, characters, ideas and images, many of which are connected. ‘Oxford is a fiction; the eponymous town is merely one of its suburbs’, writes Peter Sager in a book that traces some of these literary and artistic interactions (Oxford: Eine Kulturgeschichte – highly recommended to the Oxford intern). The list of pertinent novels, essays, letters, films, TV series, poems, songs and other texts is long, and reading recommendations are easy to ascertain.

2 Pack lightly

A ‘dusty, sequestered paradise’, that is how in his 1989 novel All Souls Javier Marias describes the second-hand bookshops in Oxford. For him they appear as dimly lit, labyrinthian spaces lined with fine wood shelving and crammed with rare first editions of obscure texts and writers only few aficionados have ever heard of. One of these places is the setting for a chance meeting with a mysterious stranger who recruits Marias’ protagonist for a secret society of bibliophiles.

Today’s second-hand bookshops in Oxford are neither dusty nor sequestered. Nor do they bear names like Waterfield’s and Thornton’s any more like in the 80s. Nowadays, the Oxford intern in search of used books, inexpensive clothes and mysterious secret societies is advised to turn to charities. The first Oxfam store opened its doors to Broad Street in 1947. It exists to this day as one among numerous shops of that description. The first one I entered after my arrival was the Oxfam in Turl Street. Instead of quiet browsing there was a radio playing, of all pieces, Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 4 – camp and decidedly British.

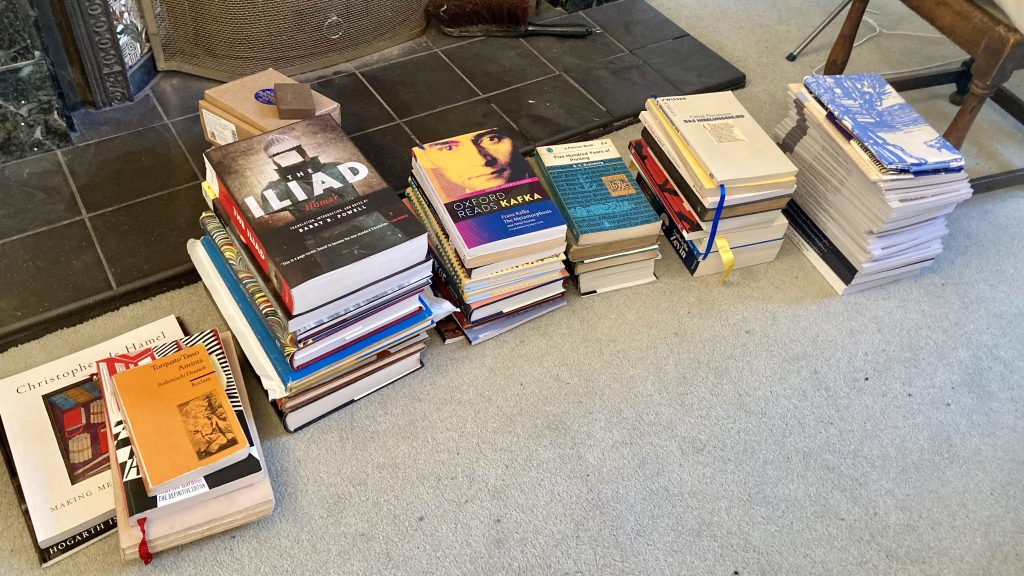

Since the UK has left the European Union, the Oxford intern is strongly discouraged from using the Royal Mail to send parcels across the channel. There is nothing left to do but to carry all the newly acquired books, clothes and secret society membership certificates in your own luggage. I have documented my last evening before leaving for Germany in these two pictures, which may illustrate the importance of packing light when coming to Oxford.

3 Don’t be afraid

The knowledge and habitus of the place, its beauty, its treasures, its table manners – all of this can be more than a little intimidating. If it is, then it helps to keep in mind that this is a shared experience. Many people feel this way, and most are very nice about it. I remember one lunch in St. Edmund Hall during which I didn’t know which bread plate to use. Was it the one on my left or the one on my right? A kind scholar sitting across the table eased the moment by telling everybody that she could never remember herself until somebody showed her a trick using both hands. Her manner was not at all patronising but kind. She then demonstrated how when the left thumb and index finger form a circle, the hand automatically appears in the shape of a lower-case ‘b’ for bread, while the right will form a ‘d’ for drinks.

Nobody expects you to know everything in Oxford, and if you don’t know something, you can almost always ask. This might be one of the most important rules. Whether I was speaking to a philologist at a conference, an academic at high table, a librarian, a bookseller, a dance partner at the Scottish Dance Society, a volunteer in a church, a hairdresser or a Grindr date, everybody had something interesting to say, and many people were generous in providing helpful or entertaining information about what they are passionate about. I am grateful to all the people inviting me to their table, into their conversations and their work.

If this assurance does not suffice to ease the Oxford intern’s mind however, they might try to cultivate just a little of the poise of Kenneth Grahame’s Mr. Toad: ‘The clever men at Oxford, / know all that there is to be knowed. / But they none of them know one half as much, / as intelligent Mr. Toad.’

4 Learn to tie a bow tie – or don’t

Before coming to Oxford, I had never even heard of a cummerband. Now I own one (£2 at Oxfam in Cowley Road). I still don’t know how to tie a proper bow tie. This ignorance can be beneficial though, as it heightens the bonding experience of getting ready together for a formal event to help each other with these things. Who needs team building in challenging surroundings like the forest when you can tie your bow ties together, instead?

5 Embrace performance

Being an Oxford intern under Henrike Lähnemann means being in the company of somebody who on a regular basis breaks into song, recites Middle High German poetry and carries a trumpet almost anywhere she goes. The love of performance however is a quality that permeates Oxford almost as a whole – dressing up in gowns, singing Evensong and Compline, entering the hall in the form of a procession. It was on May Morning, i.e. the first of May, that I understood an important rule to this theatricality. As early as 6 a.m. what feels like all of the town comes together to hear the Magdalen College Choir sing the Hymnus Eucharisticus and a saucy Renaissance madrigal from the top of Magdalen Tower. For the next few hours the streets are filled with people in costumes, dancing and music. But then people switch their ginger wine for coffee and go back to their books and talks and essays as if nothing unusual had happened. What I learned that day was that in Oxford amusement does not compromise work. If you want merrymaking, you just get up earlier.

Or, more to the point perhaps: you make it part of your day-to-day work. In Oxford theatricality and academia are deeply entwined. Numerous are the plays and performances I attended and heard of in my two and a half months there, some if not all of which were in a way connected with my study: medieval mystery plays, Seneca in – well, not Latin but a Renaissance translation –, modern takes on Kafka, an interactive performance in the Ashmolean Museum, baroque opera in the English countryside, … In a way of course, the lectures, seminars, talks, exams and conferences of academic life are forms of theatre as well. Even merely sitting in the Main Reading Room of the Taylor Institution Library by yourself, gazing at the Apollo on the portico of the Ashmolean outside, against the light of the setting sun, while searching for words to write in a second language about books you’ve only learned existed a few days ago, you cannot help but feel like you’re playing a part.

This can be a discomforting feeling, what the English call stage fright and the Germans Lampenfieber. But, as the Oxonians have showed me, it can also be great fun. Being allowed to attend the Medieval German Graduate Seminar, I was delighted to find myself every week in the midsts of a group of people who not only have insightful things to say about Middle High German courtly literature, but who also delight in taking turns reading and performing them with verve and humour. When the day of a workshop on Homer and the Nibelungenlied, which I had helped organise, came, I had to give a little performance myself, together with Mary Boyle. To add spice to it, the whole thing was of course filmed and uploaded on Youtube right away. We were amazed when after a few days, the views had skyrocketed to two thousand.

6 Remain sceptical

This is a rule for Oxford Henrike Lähnemann taught me and a small group of visitors on one of my first days. We were in the vaulted Norman crypt of St Peter-in-the-East, a church that upstairs now houses the St Edmund Hall college library. Henrike showed us a dark corner where two tombstones were leaning against the medieval walls. ‘What century, do you think?’ As we examined the stones, holding candles and looking for clues whether the carving might be Gothic or baroque, we quickly discovered the truth. The supposed gravestones were in fact painted styrofoam: a prop for an episode of Inspector Morse.

7 Go to church

Honestly, do. And everywhere else, whenever you get the opportunity. Just don’t forget to relax as well.

8 Work with objects

Oxford has wonderful objects – books, artworks and artefacts in the collections among them. When I went to a workshop called ‘Teaching the Codex’, the question being discussed was not, as you’d expect at any other university, How can we teach students about medieval manuscripts when all we have to show are digital copies?, but: How can we teach students about the incredible medieval manuscripts we have here at hand? It is an immense privilege to be able to work with what Oxford has to offer. Looking at and sometimes even touching and handling material objects can help you see things in your field of research that would otherwise have been difficult to find. I learned this on various occasions visiting the printing workshop in the Bodleian Library, working with different collections in the Ashmolean, inspecting the printing presses in the Weston Library, being shown papyri, manuscripts and printed material by experts in the weekly Coffee Mornings and other events and, last but not least, in the exhibitions where Bodleian holdings are presented to the public for free.

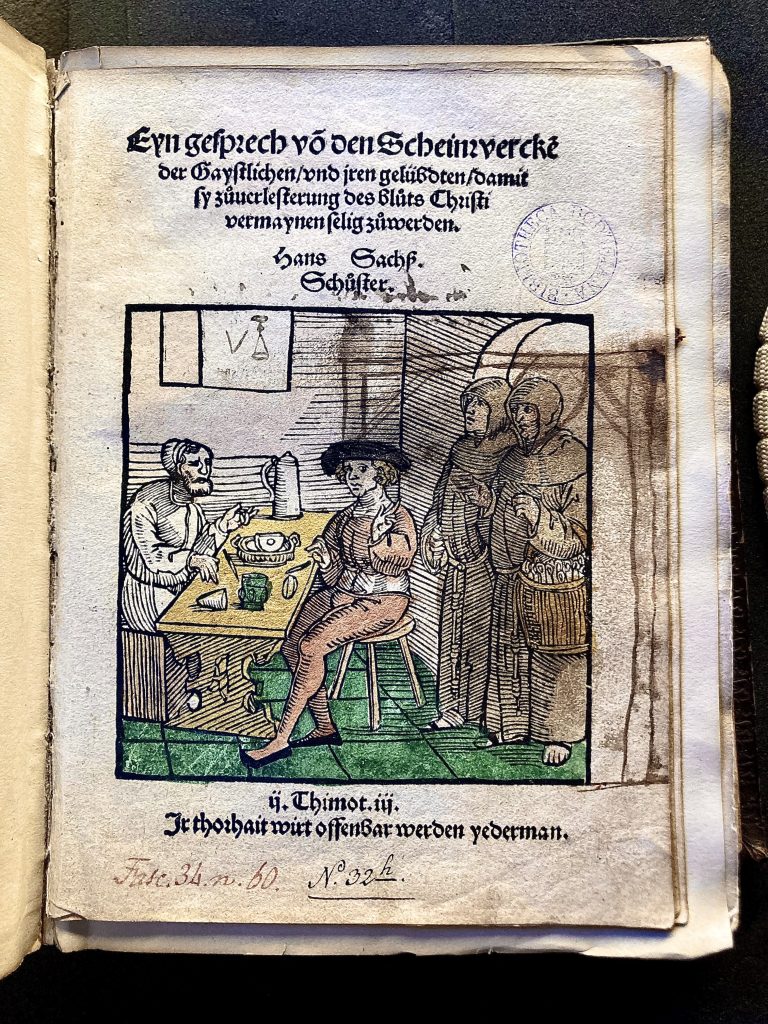

One of the projects I was involved in is an upcoming hybrid edition of the four reformation pamphlets published by the German author Hans Sachs in 1524. I spent many hours working with the thick leather tomes which are kept in the Bodleian under the shelfmark Tr. Luth. for Tractatus Lutherani. Going through the marginalia, marks and traces former readers have left in these pamphlets centuries ago, I learned more about their story, who might have owned them, how they interacted with them and how the collection ended up in Oxford. Apparently, some early reader harboured strong resentment against Catholicism. On a title page that depicts two artisans and two Franciscans, this reader drew a gallows at which they had the monks hanged by their necks. Of course, I couldn’t take the pamphlets home to work with them when I wasn’t in the library. What is the Oxford intern supposed to do in such a situation? Exactly, they print and sew their own mock-up version.

Another of the projects I was helping with was a book exhibition in the Taylor Institution Library. A photo I took during our process of putting the exhibition together may illustrate a major problem the Oxford intern might encounter when working with the collections: abundance.

9 Don’t forget when it’s time for ice cream

This is something Henrike Lähnemann said to me when we were hard at work putting together our exhibition catalogue in her office and a sentence to remember every now and then, not just in Oxford but in life: ‘And now it’s time for ice cream.’

10 The library is not for talking

‘Tread lightly, speak softly.’ When working in Duke Humphrey’s Library, I sat beneath the judging side eye of a corbel cautioning me to abide to this rule. In Oxford, as anywhere else, the library is not a place for talking. Except for when it’s half past nine in the evening and you’re wearing black tie and eating cheese and fruit in a college library, of course.

1 thought on “10 rules for an Oxford internship you’d regret not knowing”