On Friday 16 October, History of the Book students were treated to a workshop at the Bibliographical Press in the Schola Musicae of the Old Bodleian Library.

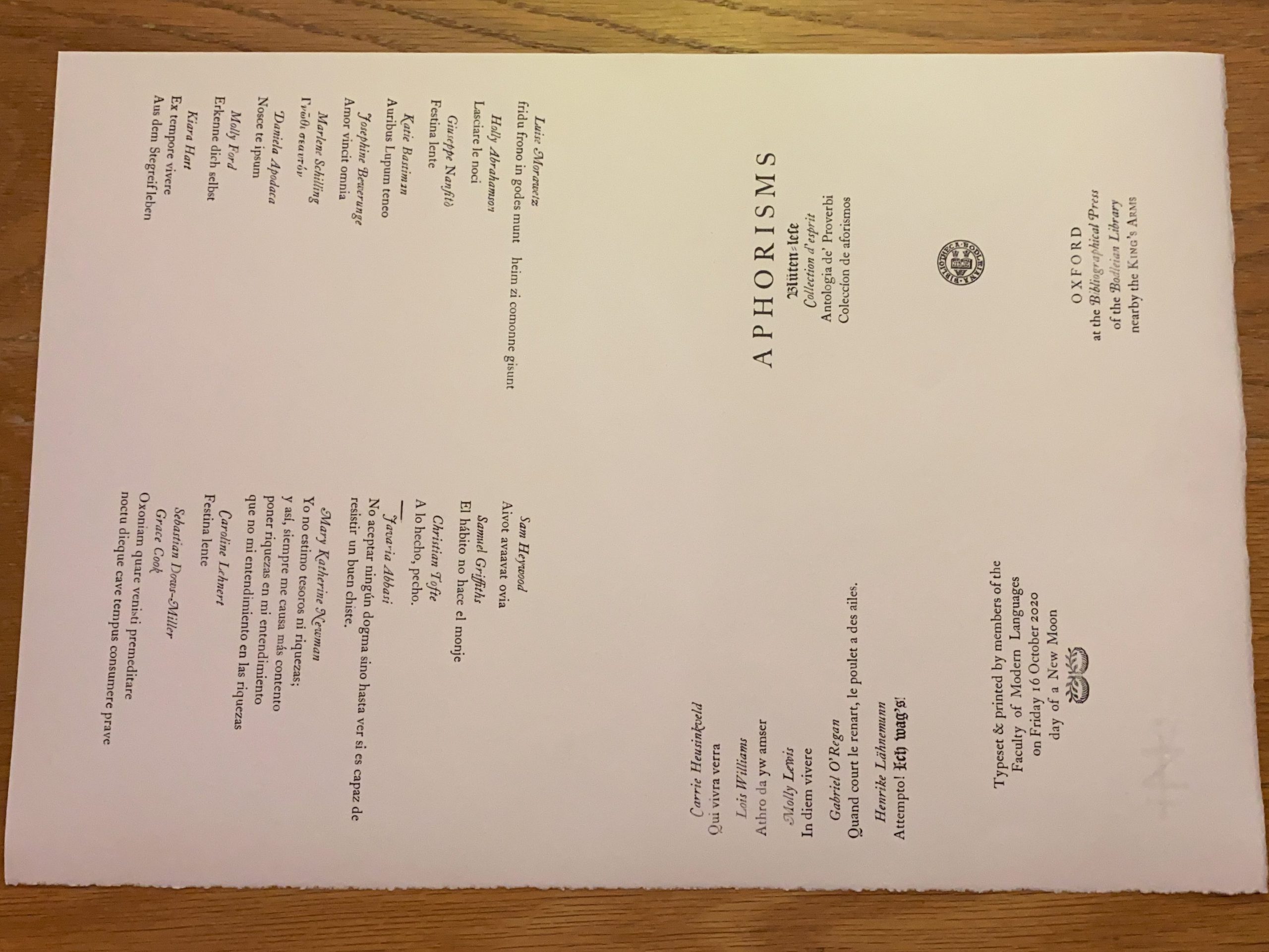

The group was introduced to the fundamentals of typesetting and letterpress-working by Richard Lawrence and Henrike Lähnemann, before typesetting a chosen aphorism, and later printing the collective effort onto a single sheet, which when folded forms a quarto booklet.

Printing was carried out on one of the Press’ four Albion Presses, the 1877 Harrild & Sons press with a platen of 11” x 16”, formerly owned by Leonard Baskin (1922-2000) and acquired by the Bodleian as part of the Gehenna Press archives in 2009.

Learning about the printing process in a hands-on way was a hugely valuable experience, not least because it revealed that while the advent of printing enabled the proliferation of greater quantities of written material at lower cost than in the earlier manuscript tradition, the printing process was still much slower and more costly than it is today, which explains the status of books as luxury objects right through into the 19th century and beyond.

In her recent history of Merton College Library (2020, the Bodleian Library), Julia C. Walworth, the college’s fellow librarian, notes for example that in the period between 1754 and 1756, the college spent £31 19s. 6d., approximately £7300 in today’s money, on just eleven printed books, including Dr Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary. I can now see how these books could be so expensive, given the manual effort required in both type-setting and printing them.

The perils of typesetting were also laid bare by the presence of what is now called a ‘typo’ in early impressions of our booklet. Never again shall I think ill of the typesetter who correctly set all but a handful of letters in a book, now that I have encountered for myself the difficulties of distinguishing between ‘p’, ‘q’, ‘d’, and ‘b’, when the types are themselves inverted and there is little to prevent a beginner typesetter from inserting a character upside down!

I continue my studies on the History of the Book with a newfound appreciation for the craftsmanship and labours of those who created these wonderful artefacts.

Sebastian Dows-Miller