This article was originally posted on the Taylor Reformation blog which has now become part of the Taylor Editions website with a dedicated Reformation Pamphlets series.

Dr Susanne Herrmann-Sinai

Luther’s On the Freedom of a Christian might leave the reader a bit perplexed. There is hardly any mention of free choice and the free will – at least not center stage as in his polemical exchange with Erasmus of Rotterdam about the topic. The text claims a Christian person is free insofar as he is a Christian, and therefore a “free lord” (freyer herr) above all things. However, no living person can only be such a free lord. Everyone, even someone with a Christian faith, is also a “servant” (dienstpar knecht) and therefore not free. The question of the freedom of a Christian man – a human being of flesh and bone who is a Christian (as in the German Christenmensch) – has steered itself into an internally split subject. What Luther seems to raise in this pamphlet is more a variation of the mind-body problem – the problem how a mental act eventuates in a physical act in the world – than a discussion of free choice.

What will bridge the split according to Luther, is not just predestination – the idea that only God knows which deeds (Werke) are truly good because they are done by a true Christian. As he argues, this idea alone would lead into fatalism (19.) – instead he combines it with an act of faith with which the Christian subject must meet this divine knowledge halfway (24.). Still, the notion of freedom contained in Luther’s overall argument – a freedom understood as responsibility and self-determination rather than mere choice – has been highly influential. This article aims to set out one example of the influence of Luther’s idea.

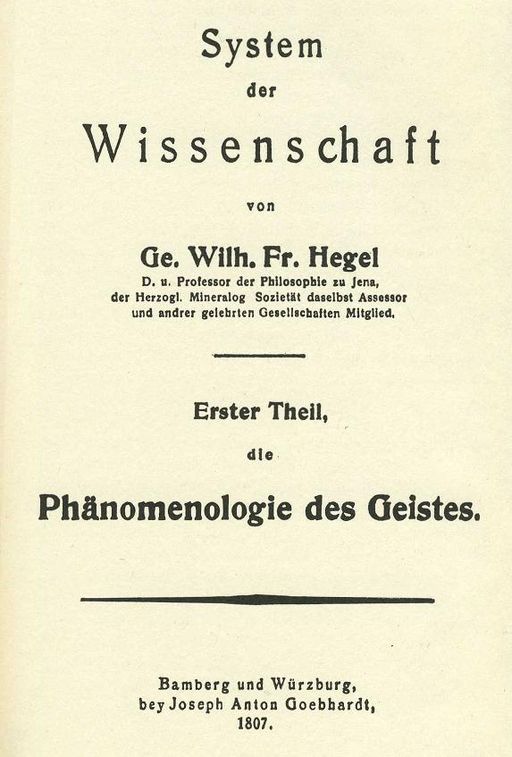

One of the most notorious passages in the work of the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel is a section with the title “Lordship and Bondage” (Herrschaft und Knechtschaft) which describes a dialectic interchange between a figurative ‘master’ (Herr) and a ‘servant’ (Knecht). Their relationship is the result of a struggle over life and death. It is a central passage in the Phenomenology of Spirit, probably Hegel’s most famous work even though written early in his career (in 1807), and finished in haste just before Napoleon entered the city of Jena where Hegel held a position as a Privatdozent (unsalaried lecturer). But the story appears again in a later publication, the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences III (published in three editions between 1817 and 1830) and it has developed its own life within Hegel’s readership and among various schools of interpretation.

While the most dominant reading takes the master and the servant to be two distinct persons who engage in a fight or struggle with each other, and allows political, sociological, or psychological interpretation, I shall argue here that Hegel is referring to the terminology, and the spirit, of Luther’s On the Freedom of a Christian, without referencing it explicitly. This means that the master-servant dialectic is an internal struggle of self-consciousness (as such) that initially appears to be a struggle between freedom and unfreedom, but ultimately challenges the notion of freedom presupposed. To do this I first sketch Hegel’s myth and then, second, argue that we have legitimate reason to establish a link and influence of Luther on Hegel. Thirdly, I provide a sketch what this influence means for Hegel’s argument – without going into too much philosophical detail.

The constellation between a master and a servant is the result of a struggle “over life and death” (PS §188) at the end of which one succumbs to the position of the servant.1 Once the two roles are established, a dialectic unfolds, where the master seeks recognition from the servant. He soon realizes, however, that being recognized from someone inferior like his bondsman does not offer the recognition he is seeking. In turn, the servant has the freedom to recognize the master despite his own bondage, which ironically makes the servant more free than the master. On top of it, the servant can realize how much the master depends on him. While the master can will things, the servant is needed to do the work and to execute that will. Therefore, the master remains in the dependence on the servant’s existence and work and thus of his own bondage to the servant. He is ultimately less free than his servant.

One of the most dominant interpretations dates back to the Russian émigré and philosopher Alexandre Kojève, who lectured on Hegel’s Phenomenology in Paris in the 1930s.2 Influenced by the philosophy of Karl Marx, he used this background to make sense of Hegel’s work. In his reading, the master and the servant are taken to be literally two persons in a relationship of serfdom. With his Marxist background however, it is not a huge step to read the two roles as a symbol for class struggle. Members of Kojève’s audience making their own uses of his interpretation of Hegel included Maurice Merleau-Ponty and it influenced Jacques Lacan and Simone de Beauvoir amongst others. The latter read the master-slave dialectic as a metaphor for gender relation in The Second Sex.3 In all these interpretations, however, the master and the servant are quite literally taken as two distinct and different entities (persons, classes, genders). Although the claim that a person can only be a free person with others might not be entirely wrong, and at the end of my article I briefly return to this, there are at least two objections to this line of interpretation.

The first objection relates to the contextualization of this passage within Hegel’s terminology of the Phenomenology, which is not straightforwardly to be interpreted in social terms. The Phenomenology is concerned with the development of self-consciousness, but it is not until much later sections of the book that Hegel deals with the relationship of individuals with each other (in a family and a state, for example). The section when Hegel introduces his master/servant myth, however, appears in the earlier sections which are concerned with the development of consciousness towards self-consciousness and the dynamic formation (Bildung) of self-consciousness. In simple terms the question Hegel is tackling here is whether we are conscious of ourselves as a person or someone else as a person much the same way as we are conscious of objects in the world, such as tables and chairs. There is no mention of a society, or a multiplicity of individuals or persons, engaging in an argument, struggle, or fight. As much sense as the above-mentioned Kojèvian interpretations might make on their own, what remains unclear, and uncommented-on, is how these terms of “master” and “servant” stand in the context of Hegel’s own systematic language, which revolves around the relationship of subject and object, rather than the relationship of person to person. With Hegel himself, we are not yet at this later, social, stage of consciousness.

The second objection is to anachronism. Reading the philosophy of Hegel through the lens of Marx as one of his intellectual descendants, or through the later reception of his work in social philosophy, is not obviously an appropriate avenue for understanding the original line of his thought. Although retrospection can illuminate, a more promising beginning is to read him from his own tradition and his own framework of scholarly and intellectual reference.

I turn now to my second contention, the likelihood that there was an intellectual connection between Hegel, and the work of Luther. When Hegel was 18 years old, he enrolled at the Tübingen Seminary (Tübinger Stift) in Würtemberg. Between 1788 and 1793 he first read two years Philosophy followed by a three year course in (protestant) Theology. The Duchy of Würtemberg followed the Lutheran branch of the evangelical church, not the reformed one. Although there is little written evidence, we can assume that Hegel’s study involved reading at least some of the key texts by Luther, the theological force of whose thought was still felt 300 years on.4 Indeed it could have been that given Luther’s place in protestant theology his writings were so well known that they hardly needed a reference and that metaphors, allusions and stories from his writing almost served like a lingua franca among students. One source for these would be the theological pamphlet addressing the idea of freedom, especially when freedom became ideologically resurgent in the French Revolution which was so enthusiastically discussed by Hegel and his room-mates Friedrich Hölderlin and Friedrich Wilhelm Schelling.

The Seminary also provided another link to the work of Luther in the figure of Friedrich Niethammer, a few years older than Hegel. They belonged to the same discussion circles and Niethammer became a lifelong friend and associate not only of Hegel but also of Johann Gottlieb Fichte and other key philosophers of this time. Of interest here is the fact that Niethammer, who later in life became an editor of Martin Luther’s sermons, assisted Hegel with the manuscript of the Phenomenology of Spirit.5 Here, we have a figure central to Hegel’s life and thinking, who was himself travelling the disciplines between philosophy and theology and who knew Luther comprehensively.All in all, the link between Hegel and Luther was obvious enough for Heinrich Heine, concluding his Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland with an extended discussion of Hegel’s influence and importance, to have originally given its original (1834) publication in French the title De L’Allemagne depuis Luther.

If given this context we assume that Hegel’s terminology of Herr and Knecht goes back to Luther, how should we now understand Luther’s thought about this matter, in relation to the interpretations of Hegel’s master-servant dialectic that I outlined earlier? Establishing the link between Luther and Hegel does not mean, that Luther himself already used or implied the notion of mutual social recognition. If this were the case, such a reading would have to look for ways of interpreting the master and servant metaphor in Luther as two persons or even to think of the relationship between men and God as one of Herr and Knecht.6 Luther’s text, however, provides no evidence for this reading.

Instead, he makes it thoroughly clear, that master and servant are inner divisions within one person, i.e. within a Christian. Together with the antonym of master and servant, Luther uses the pairs of spiritual and carnal (geystlich / leyplich), the distinction of St Paul between new and old (new / allt), as well as inner and outer (ynnerlich / eußerlich) to emphasize the same division within man’s nature. Moreover, Luther quite plainly does not speak about two people, one Christian and one non-Christian. Instead, he speaks of the very same person under two perspectives or conditions: firstly, insofar as he is with God (Herr), and secondly, insofar as he has to live on Earth and has to interact with other people there (Knecht). In this earthly condition of interaction man inhabits his servant nature, as explored in the following passage:

“nonetheless in this physical life they still dwell on earth and must govern their own bodies and deal with people.” (20. b4r)

(„So bleybt er doch noch ynn dißem leyplichen lebenn auff erdenn / und muß seynen eygen leyp regiern und mit leuthen umbgahen.“ (20. b4r))

Finally in my third exploratory step, with this reading of Luther’s text in mind we may return to Hegel and the question of what this relation of influence might mean for Hegel’s own thought. There are some interpretations of Lordship and Bondage, which address it as an intra-subjective struggle rather than an inter-subjective one.7 In these, the servant symbolizes the empirically constrained, living body without which the pure will (master) remains unable to exercise what it chooses and commands. Hegel thus begins with Luther’s distinction, but at the same time develops his own narrative in which the self-consciousness strives to overcome the split self though Bildung (the servant develops skills that enable him to leave his position). These are certainly readings which do not only appear to be more sensitive to Hegel’s own text, but also in line with the tradition of thought stemming from Luther within which, I have suggested, we can place Hegel.

Reading the master-servant passage in Hegel as an intra-subjective struggle in line with Luther does not mean, however, that there is no place for inter-subjective recognition between different persons in Hegel. Indeed, it could be argued that this idea also has links to Luther On the Freedom of a Christian. Towards the end (27.) and most prominently in the concluding paragraph (30.) Luther summarizes the two principles of Christian life as a free life lived in faith and love of one’s neighbours. While Luther’s notion of “faith” deserves its own discussion, the address of “neighbours” in a Christian’s life lifts other persons to a level beyond the simple “to deal with people” (20.). Instead, people as neighbours become a crucial part of what freedom must mean according to Luther. Here, he articulates the idea of other persons or a community between Christians as essential for the freedom of a Christenmensch. Whereas Luther’s text began with a split subject within which only one part (master) seemed to be free,8 it ends with these two principles which taken together constitute the freedom of a Christian made of flesh and bone and thus of the way he sees the gap caused by the internal division of a person to be bridged.

Two important conclusions spring from here: Firstly, from this perspective, a Hegelian idea of mutual social recognition is the secularized sister of the Christian “love thy neighbour”. And secondly, in the tradition springing from Luther and spanning to the philosophers of German Idealism, freedom is not reducible to mere freedom of individual choice, but involves the idea of this individual being part of a social realm, such that one is not free alone but becomes free with others.9

Susanne Herrmann-Sinai holds a PhD on the philosophy of G.W.F. Hegel by the University of Leipzig and is currently an Associate Faculty Member at the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Oxford. Her interests are the philosophy of German Idealism, particularly Kant and Hegel and specifically Hegel’s notion of ‘spirit’ and she has published articles and volumes in these areas.

susanne.herrmann-sinai@philosophy.ox.ac.uk

Notes

The passages that use the words Herr and Knecht in Hegel have been translated in a variety of options. James Baillie uses ‘master’/‘lord’ and ‘bondsman’ (1910) and Arnold Miller (1977) and Michael Inwood (2018) follow him there. However, an English translation of the French philosopher’s Alexandre Kojève influential lectures on Hegel uses ‘Master’ and ‘Slave’ (James Nichols 1969) and Terry Pinkard chose ‘master’ and ‘servant’ for his 2018 translation of the Phenomenology. I am following the translation of the edition to which this article is linked with ‘master’ and ‘servant’, because a servant has a will, whereas a ‘slave’ less so.

2.

Later publishes as Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit, 1947 (engl. transl. by James H. Nichols, 1969 Basic Books)

3.

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, transl. by Contance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevalier, London: Vintage Books 2011, p. 73.

4.

What we do know is that Hegel must have studied with Gottlob Christian Storr, who discussed Kant’s philosophy (Walter Jaeschke, Hegel-Handbuch. Leben – Werk – Schule, Metzler 2010, p. 5.) – Because the philosophy of Kant frequently serves as a background for Hegel’s arguments, it can be argued, that Hegel was addressing Kant through the concepts offered by Luther.

5.

Entry: „Niethammer, Friedrich Immanuel (1766–1848)“, in: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers, edited by Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn, Continuum 2010.

6.

Cf. Robert Stern, „Luther’s Influence on Philosophy”, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/luther-influence/index.html (accessed 9th November 2020).

7.

Among those cf. Pirmin Stekeler-Weithofer, Philosophie des Selbstbewußtseins. Hegels System als Formanalyse von Wissen und Autonomie. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp 2005 and John McDowell, Having the World in View. Cambridge, Mass./London: Harvard University Press 2009. Markus Gabriel stresses the mismatch of the orthodox readings with Hegel’s own passages (“A Very Heterodox Reading of the Lord-Servant-Allegory in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit”, in: German Idealism Today, edited by M. Gabriel, and Anders Moe Rasmussen, De Gruyter 2017). One of the clearest accounts of the master-servant passage in terms of physus and logos can be found in John Russon, The Self and its Body in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, Toronto: University of Toronto Press 1997, ch. 3, p. 53ff.

8.

And some stress primarily the impact this division had on the philosophy after him: Thomas Wendt, „Kritische Philosophie, philosophische Kritik. Bemerkungen zur Gegenwartskrise der liberalen Kultur und ihrer Denkungsart“, in: Philosophie und Epochenbewusstsein. Untersuchungen zur Reichweite philosophischer Zeitdiagnostik, hg. v. Matthias Janson, Florian König, Thomas Wendt, Würzburg: Könighausen&Neumann 2020, S. 29–66.

9.

My thanks goes to Louise Braddock, David Merrill, Filip Niklas, and Robert Stern for reading versions of this paper.