Clara Busch, MSt. Modern Languages 2023-24

It is Monday, January 8th, and a small group of students and scholars gather it the Weston Library to have first look at what is to become the focus of our History of the Book project: Kafka’s Hebrew notebooks. 2024 marks the centenary of the death of Franz Kafka and all of Oxford is excitedly metamorphing into a collective celebration of Kafka’s work and legacy. The Archive of Franz Kafka is among the holy grails of the Bodleian Library and manuscripts are only to be handled by experts and with utmost care. It is therefore even more exciting that two of us HoB students got to work with the Hebrew notebooks this year, testing our knowledge of digital scholarship methods and learning about Kafka’s endeavours to study Hebrew.

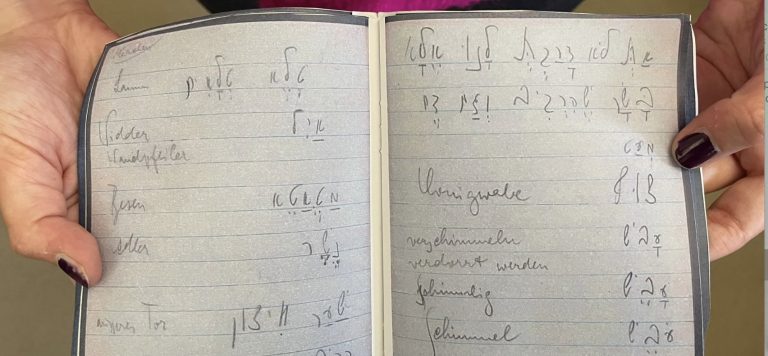

From five Hebrew notebooks available in the Bodleian, we focussed on MS Kafka 33 which contains German-Hebrew exercises, small fragments, and a list of books and readings. Among the other Kafka notebooks and manuscripts held at Oxford, the Hebrew notebooks are dated closest to his death in 1924, a time where Kafka engaged more actively in learning Hebrew, both with a tutor and by his own initiative.

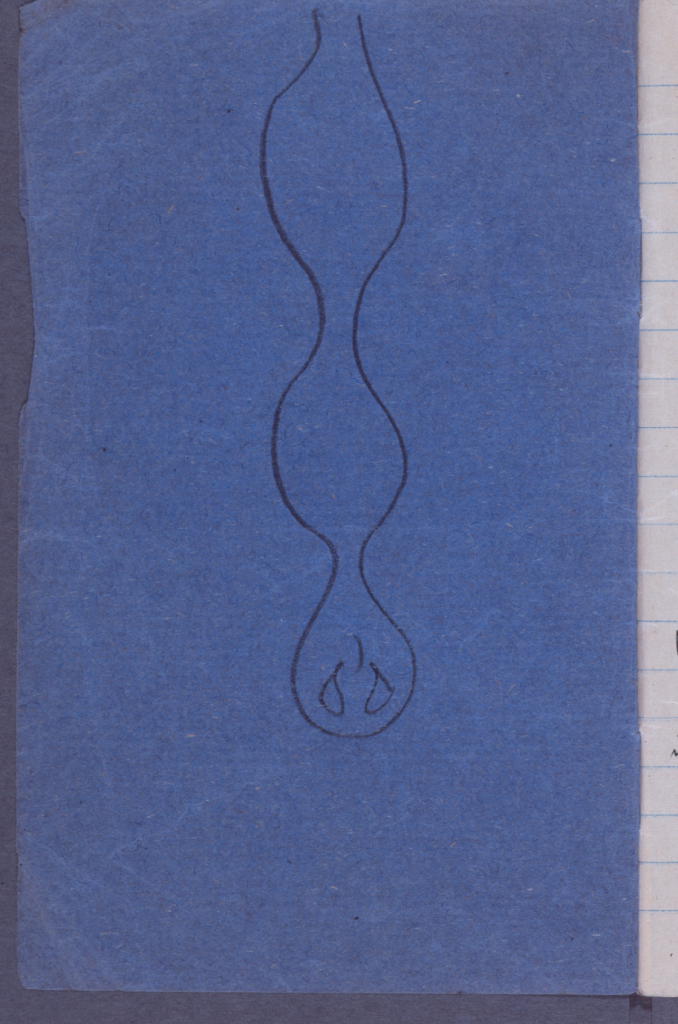

While the first three of the classic, small, blue vocab books contain blank paper, MS Kafka 33 on which Kafka wrote mainly with pencil and occasionally with black ink. Notes and writing in black ink seem to have been added at a later stage and are sometimes squeezed in-between vocabularies written in pencil and a smaller font. A special highlight in this fourth notebook is a small doodle Kafka drew on the inside of the front cover. The figure is interpreted to depict either a snake of ghostly figure, most likely as a form of (gate) keeper or guardian.

Due to the notebook’s fragility and importance, we worked with digital images which allowed us to zoom in as close as possible to decipher Kafka’s handwriting, compare different folios and even words side by side as well as screenshot and cut out individual vocabularies. Although it was obvious from the start that a fully manual transcription will be necessary, I ran some excerpts of the notebooks through Transkribus – with no success. Kafka’s 20th century cursive proves much too irregular for a text recognition software and the bidirectionality of the German and Hebrew text added to that.

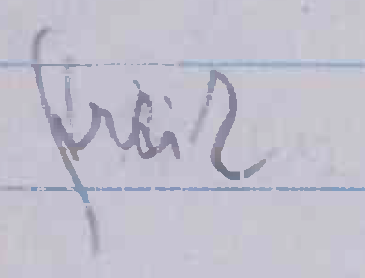

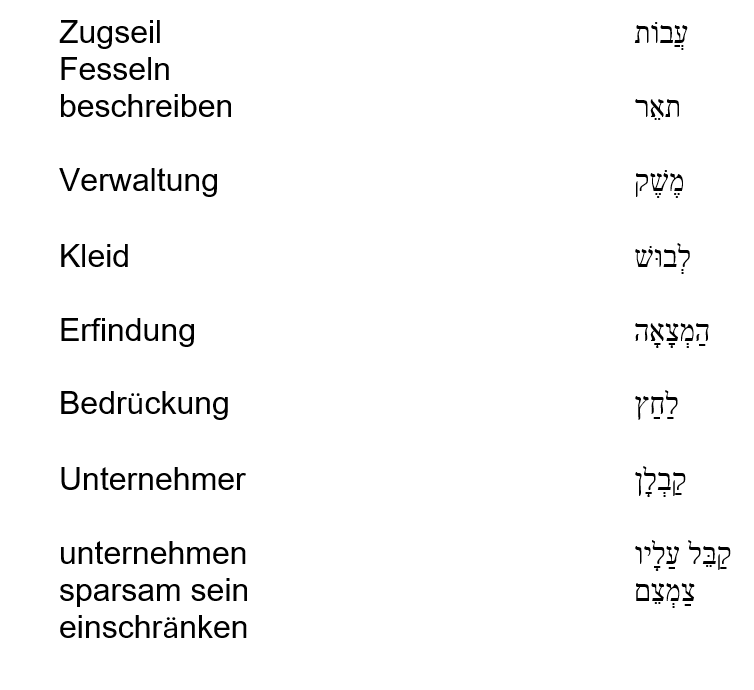

Reading Kafka’s handwriting proved difficult in the beginning but got progressively easier once the intricacies of his cursive become more familiar. For a little taste…

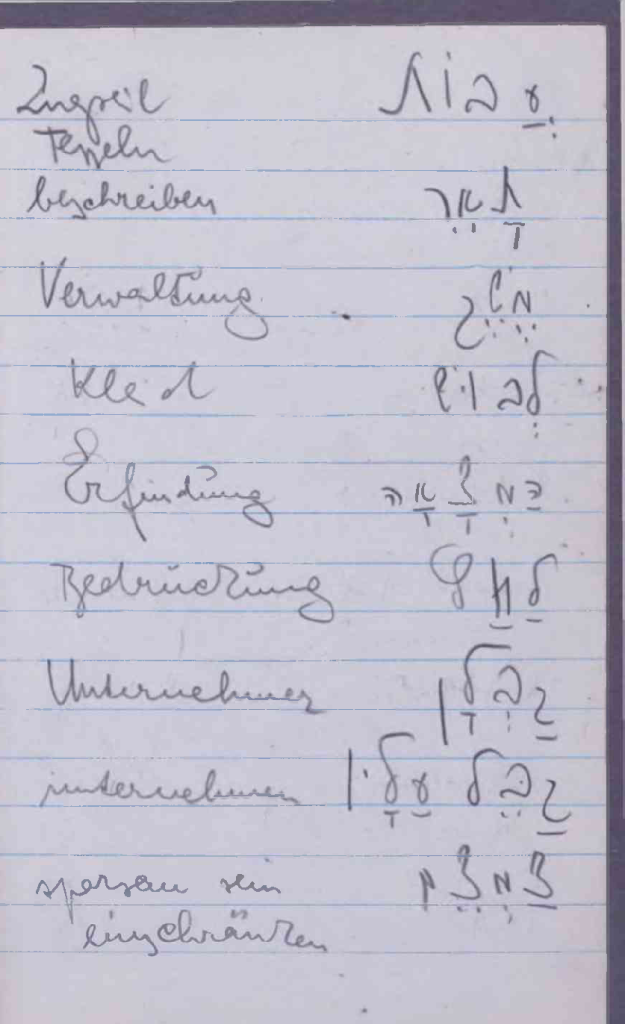

Transcribing the Notebooks

Transcription example: fol. 9v

It is striking that the word lists do not seem to follow a logical order or theme but are seemingly randomly assembled as vocabularies unrelated to one another are immediately adjacent. This obvious incoherence of the German words suggests that insight into the selection of vocabularies and linguistic context is to be found within the Hebrew. In 1923, Kafka returned to studying Hebrew after a break due to illness, under the tutoring of Puah Ben-Tovim who was born in Jerusalem and came to Prague to study mathematics. Since Kafka did not simply conduct the exercises on his own, it is likely that his tutor taught language based on the Hebrew roots which then dictates the German vocabularies.

Throughout the engagement with the notebooks and the transcription process, we stumbled over the inconsistencies in translation between the German and Hebrew, especially in their respective translation into English. Ruling out our own mistakes in reading and transcription it is possible that where the German meaning deviates from the Hebrew, Kafka – as a pupil of language – made mistakes in spelling or punctuation.

While we cannot be sure about the specific word choices or strategy behind the vocabs, each folio and list offer a glimpse into Kafka’s (and his tutor’s) approach to studying Hebrew and invite speculation as to what he was currently thinking and writing about. Why could Kleid, Erfindung, and Bedrückung (dress, invention, and depression) possibly have in common?

The exhibition ‘Kafka’s Languages‘ is now open in the Voltaire Room of the Taylor Institution Library