Following our foray into textual encoding last week, Dr Giles Bergel joined us from the Visual Geometry Group (https://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~vgg/) to talk about book-historical uses of computer vision. Originally trained as a book historian, Dr Bergel gave us an overview of the theory behind it, how it has been used in humanities projects, and what computer vision can teach us about the material objects in front of our own human eyes.

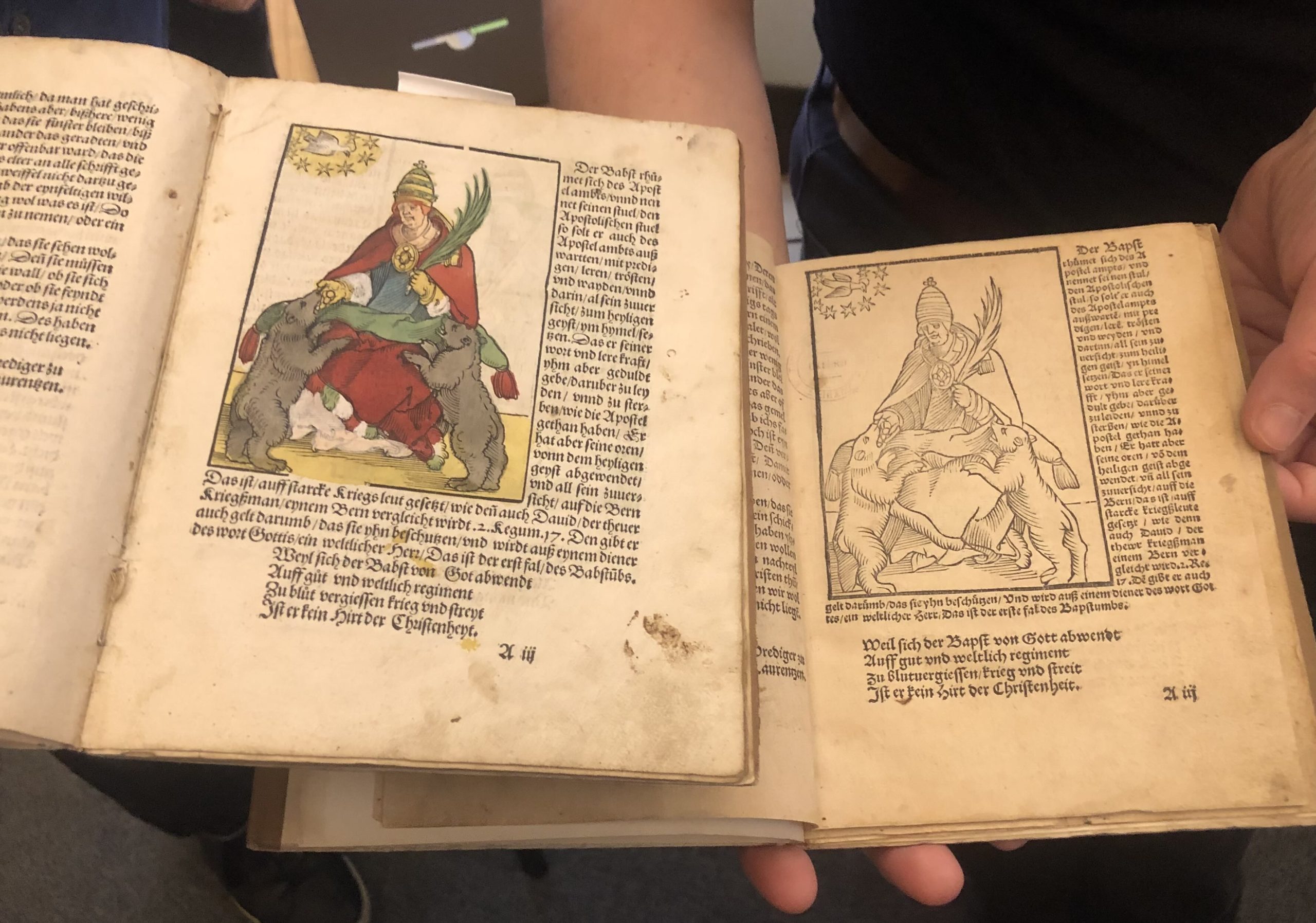

Dr Bergel opened the session by outlining the broader picture of computer vision: recent projects have used it to track and record live sign language and even recognise individual animals such as chimpanzees in the wild. For literary texts, computer vision has been used to track and compare illustrations and their layout on a page. However, whilst this may sound like a simple game of ‘spot the difference’, working with a large set of images with minute differences makes a computer far more adept at this task.

One example which Dr Bergel showed us was the project 1516 : A Visually Searchable Database of Printed Illustration from the 15th and 16th centuries. Deriving from earlier work on Scottish chapbooks, this database allows users to search for images both in the metadata or by uploading an image. Much like Google Images, the computer’s algorithm is able to pinpoint certain ‘keypoints’ or features to compare within the dataset.

This, for instance, can reveal the story of how one block (here Block 7: Man, full length) deteriorated over time as woodworms burrowed into it and re-emerged, leaving circular gaps in the woodcut. To find out which other woodcuts were a woodworm’s favourite and more, see the Bodleian Ballads blogpost about this. Thus, this example demonstrated how computer vision highlights the material history of literary production as woodcut blocks are passed down through families, sold to other workshops, and worn away over time.

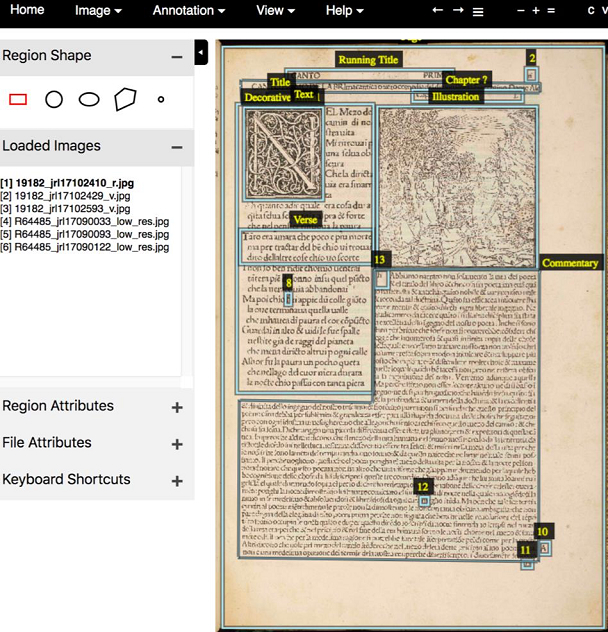

When we moved away from the illustrations themselves to considering the page layout as a whole, it raised the interesting question of where does the page end. It is easy to forget the impact of the typesetter’s composing stick on the page as text and image are forced around each other in whatever way possible. Dr Bergel illustrated this through the ‘Envisioning Dante, c. 1472-c. 1630′ project (ENVDANTE) where Professor Guyda Armstrong, Dr Rebecca Bowen and himself explore how page design shaped Dante’s print reception. Moreover, as a computer deals only with single pages, we can neglect seeing the double page spread as a unit of its own where the two individual pages interact with each other.

Hence, we are once again brought back to how important and revealing materiality can be. Through these AI-assisted tools, there is much that researchers can learn about their own objects at hand, especially that which the human eye cannot see. Tracing histories of workshops and woodcuts and re-thinking how we engage with books, computer vision is truly visionary to its core.

By Lucian Shepherd, MSt Modern Languages 2024/25

Featured Image Credit: Figure 10 taken from: Chapter 30 ‘The Use and Reuse of Printed Illustrations in 15th-Century Venetian Editions’ by Cristina Dondi, Abhishek Dutta, Matilde Malaspina, Andrew Zisserman. DOI: 10.30687/978-88-6969-332-8/030