By Isabelle Riepe

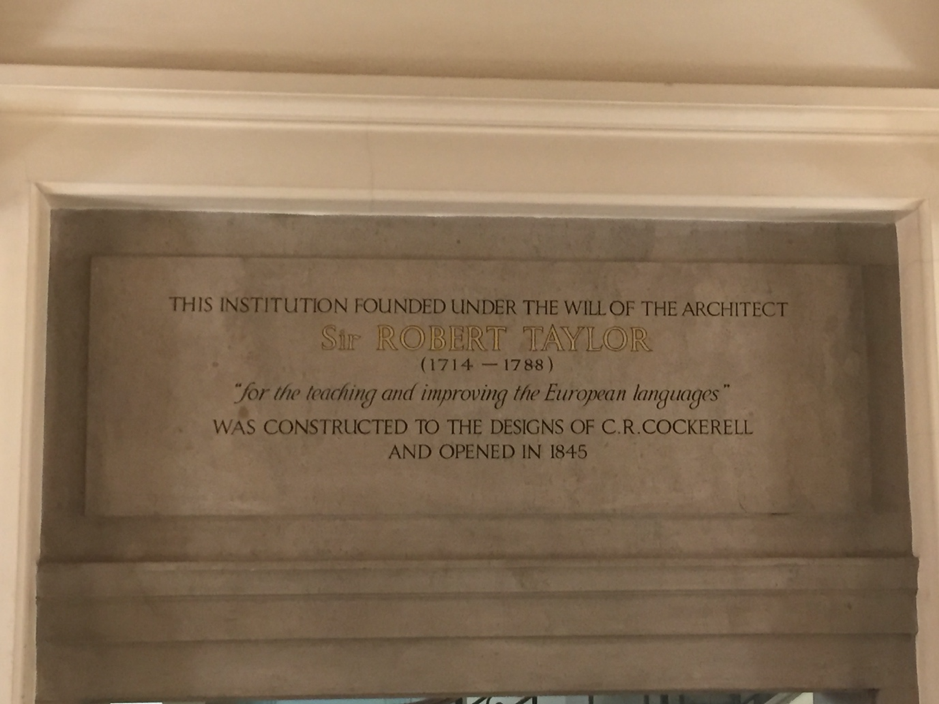

A library must not always be just books. Libraries established before the 20th century mostly originated from collections, alongside objects, like porcelain, clocks, furniture, or paintings. Sometimes those also find their way into a newly founded library of the 19th century. The Taylor Institution Library (Taylorian) opened in 1849, following the will of architect Sir Robert Taylor (1714-88), ‘for the teaching and improving of the European languages’.

Alongside the Bodleian and the Ashmolean it was then, the only site for teaching, learning and storing of collections which included non-book items like paintings, coins and other bits of decorative art. Thus the Taylorian held the Hope Collection of Entomology and naturally evolved into a cabinet of curiosities – a renaissance pastime from which libraries, museums and galleries spawned. Non-book items are instinctively occurring in libraries that have witnessed tumultuous times in history to capture memorable moments or store and preserve things safely for prosperity. Objects however are a challenge to be listed in a traditional library catalogue, which is why endeavours like ‘the treasures of the Taylorian’ are undertaken separately.

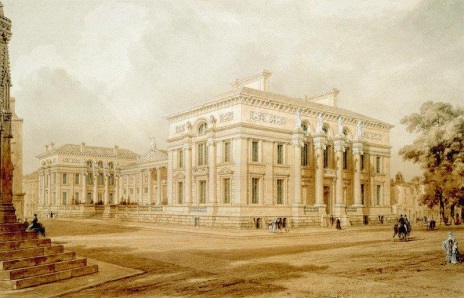

From http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2014/09/2014-09-TayBldg-C19thImate.jpg

The Taylorian’s imposing architecture and the impressive and comfy reading room on the first floor are typical for a Victorian library and render it a unique and beautiful studying spot for students today. Decorations of inner and outer façades are rich with symbolism. So much so, that it is still debated who the four female figures at the top of its outer façade actually represent. The main four European language studies (Italian, French, Spanish, German identifiable by its leading writers of that time engraved on the plinths) in the 19th century? Or actually the four daughters of curator Dr J.A. Ogle, the Regius Professor of Medicine, which some inhabitants of Oxford propositioned?

Such mysteries render the Taylorian too a treasure in and of itself. The building continues to (be) a-maze. One almost feels like walking through Crete’s labyrinth to arrive at – instead of the threatening Minotaur at its heart – the Voltaire room under the scrutinising eyes and mischievous grin of not only one but three Voltaire bust watching its readers and guarding the Taylorian’s exhibition space.

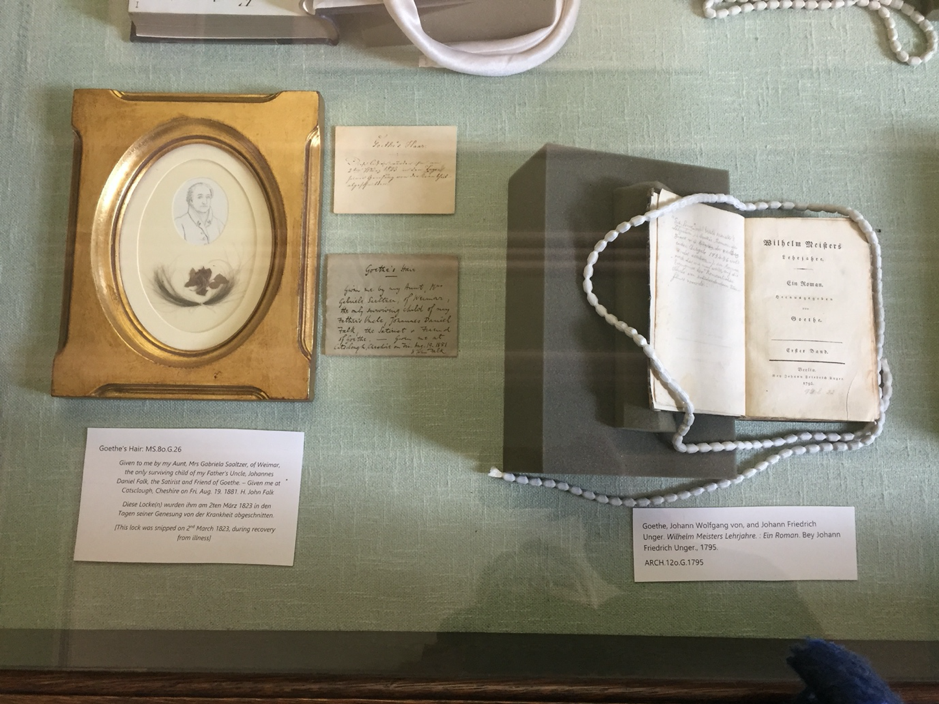

I want to focus on the Voltaire Room as a library space that is not accessible to non-Bodleian Card holders which highlights important aspects and dilemmas libraries as architectural and intellectual institutions encounter today. Stepping into the Voltaire room for the first time, I beheld a slightly adapted cabinet of curiosities. Books on all four walls maintained the Victorian library aura of the Main reading room, but busts and wall decorations as well as lighting gave it a classical but rather cold and clinical feel, only reinforced by the wooden chairs and tables provided as workspaces. The contrast however provides a stimulating alternative to the comfy earth-tones of the main reading room. It also draws your eyes to the prominent wooden exhibition cases that show temporary displays curated by the Taylorian’s librarians or students. A recent exhibition showed the German book and non-book treasures the Taylorian holds, including a lock of Goethe’s hair!

The Voltaire room is one of many rooms in the Taylorian that enable their readers to partake in books and non-book items living together, their symbiosis. Dozens of busy and stressed students, librarians and academics dip in and out, leaving their trace and thus enriching the spirit of place. This may be the sounds of typing, thumbing through pages, huffs and coughs or the stacks of books lying around on the original 19th century furniture providing welcome distractions from your own work. All is framed framed by wall-high bookshelves, paintings and busts, occasionally interrupted by the faint ticking and ringing of the French black marble clock over the unused fireplace.

All this highlights that we need patience and openness to appreciate the spaces and contents in them, only then are we receptible to them: Calm down, relax and let inspiration take you. We should also beware of the privilege of our enjoyment of such a beautiful study space, which is ironic when considering that books should be the most easily accessible item to everyone. Reading especially in a context like Oxford’s seems like second nature to us, as essential as breathing almost, which makes us forget that not every country, not every university, not every school has the means, the people and the opportunity to enable those experiences.

But not all is lost and inaccessible thanks to the world wide web! Insight into the deeper currents of the Taylorian’s book treasures provide publications entitled Treasures of the Taylorian which range from Martin Luther’s pamphlets and letters to the multilingualism of Yoko Tawada. The exhibitions, which spawned publications, are accessible online too.

As part of our History of the Book, Palaeography and Digital Humanities postgraduate module we students also learn how – and Professor Henrike Lähnemann never tires to encourage us – to share our research, our findings, impressions and thoughts online to let others partake.

We can increasingly witness how libraries have become social spaces or assist in creating alternative spaces to come together and work collaboratively – be that as a traditional working and reading space enhanced by an opportunity for curating an exhibition or discussions and images shared through social media. Oxford’s many libraries share similar approaches with varying outputs and outcomes, have a look at the Weston libraryfor example.

To close with Professor Cristina Dondi’s recent remark in one of our Wednesday afternoon sessions about 15thcentury booktrade… The book should return to our attention!

References

Giles Barber, A Continuing Tradition: Non-Book Materials in the Taylor Institution Library, The Bodleian Library Record, 17 (2002) pp.261-292

Jill Hughes, ‘History of the Taylor Institution Library and its Collections’, 13 November 2014, Taylor Institution Library <http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/2014/11/13/history-of-the-taylor-institution-library-and-its-collections/> [Last accessed: 22 November 2019]