by Clara Busch (MSt. Modern Languages)

Once more it is the first week of Michaelmas in Oxford and a new cohort of graduate students embark on their journey through the Modern Languages and, most importantly, the History of the Book(s). On this first Wednesday of term students, scholars, librarians, and fellow Bibliophiles gathered in the Taylorian to discuss, examine, admire, and stroke – literally and figuratively – a number of books and manuscripts from the special collections. Students also brought along a book, manuscript, a picture of a book they could not fit into their suitcase when travelling to Oxford, or any other object they associate with the term “book” and hold close to heart.

Encouraged to bring a personal bookish object – the more varied and peculiar the better – to introduce ourselves in the manner of true Humanities students, it was fascinating to witness the different associations a single task can evoke. Read on to get a glimpse of what we got to marvel at during the first class of term.

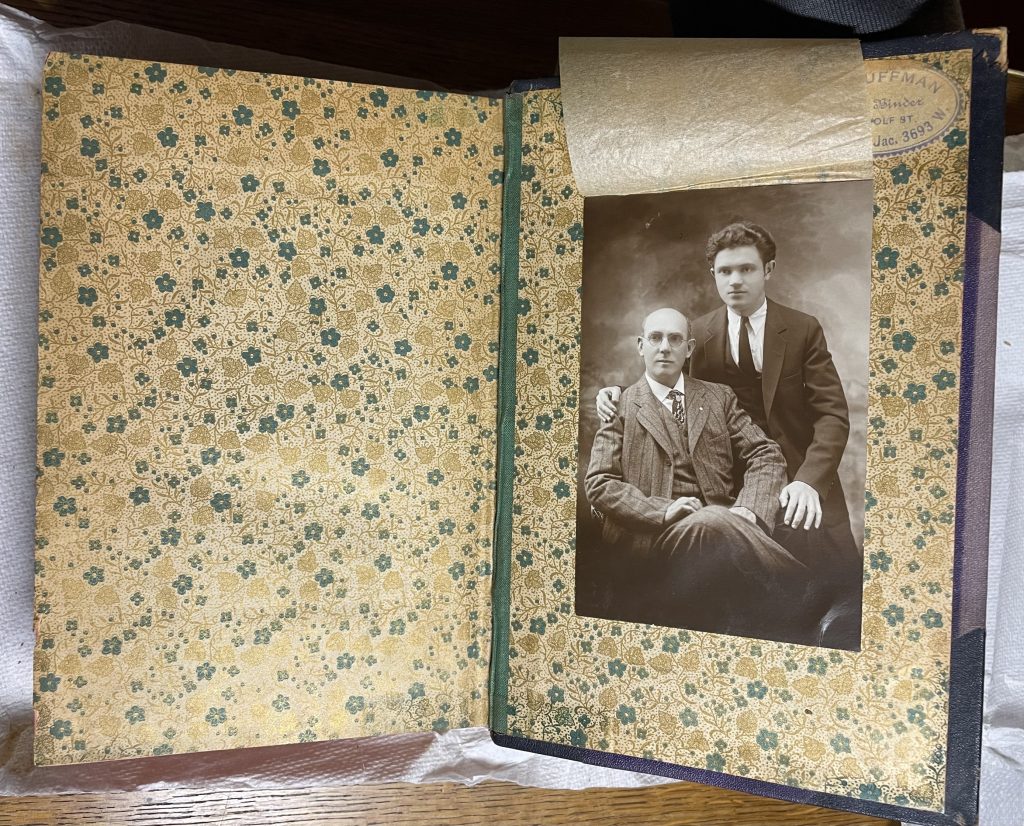

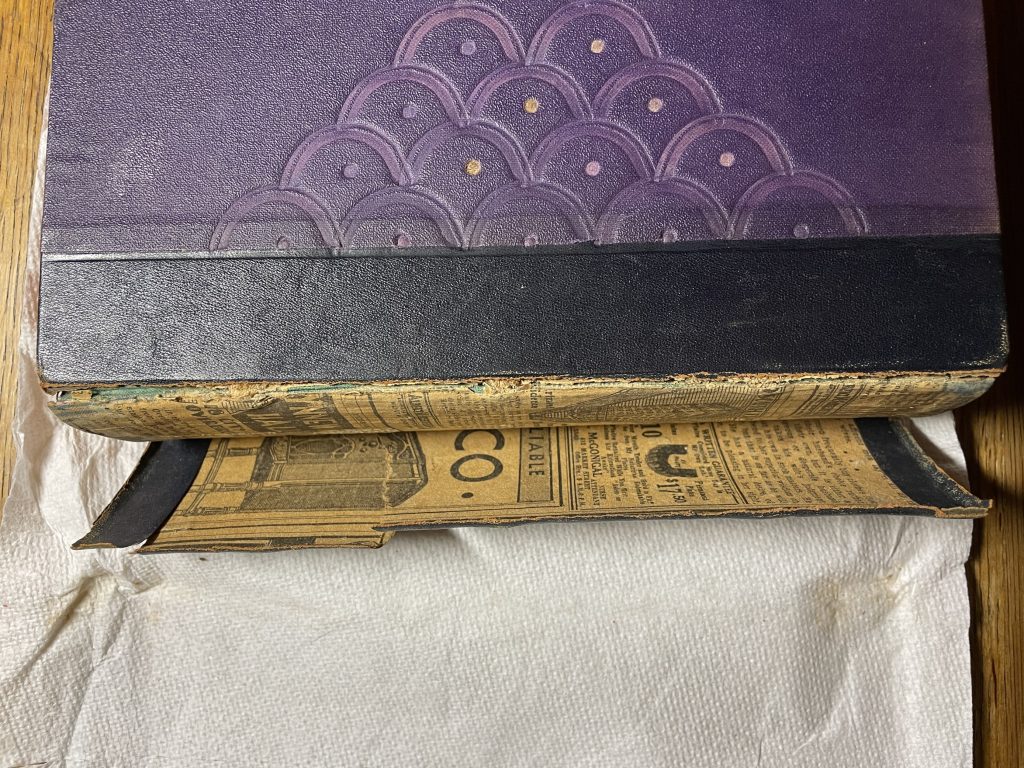

One of the first to present her book was Giovanna, who brought along a parting gift from David Mazower, the bibliographer of the Yiddish Book Center, as she was en route to Oxford. The selected works of Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh, popularly known as Mendele Moykher-Seforim, is a book in Yiddish which does not only contain several photographs and clippings but also reveals newspapers in English used for the binding of the now deteriorating spine. Even though the newspapers were clearly used as scrap paper, Giovanna wonders what meaning can be derived from written work sealed away from the user’s eyes. Take, in contrast, the meaningful pieces of writing sealed in a mezuzah, a scroll placed on the doorframe of a Jewish home as a reminder of the commandments in the Torah. With her book and explanation Giovanna contemplated and made all of us wonder: What does the book as an object “mean”? To her, this book represents the conflicting impulses of her longing for home and her inspiration to go out into the world to study Yiddish.

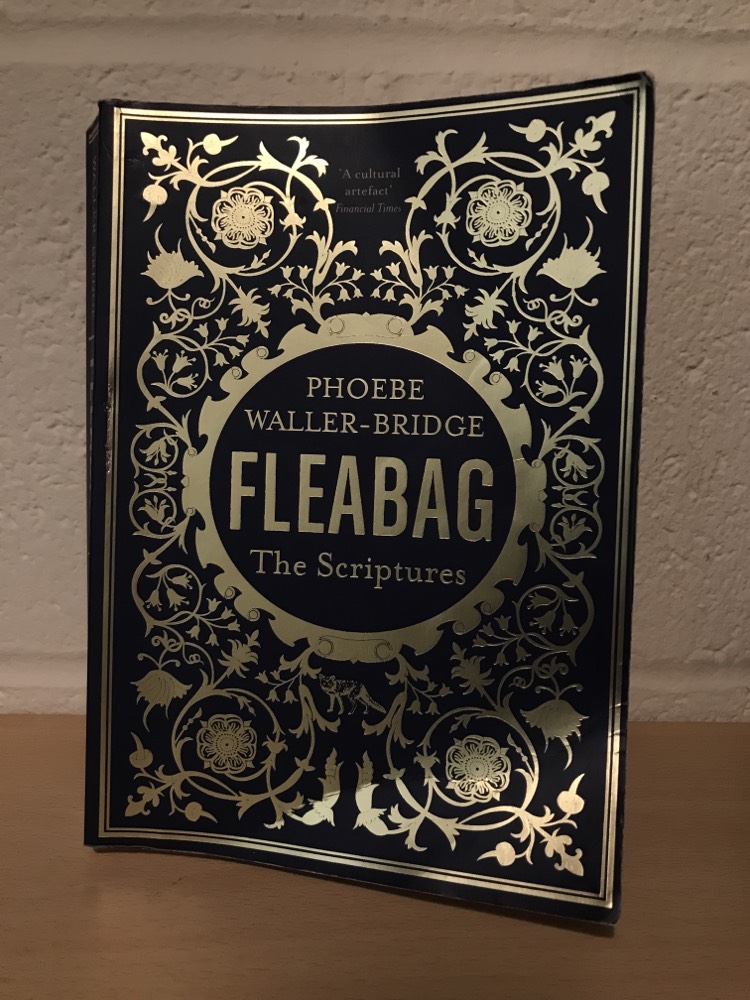

Almost as to point out the variations in the books and personal object we got to look at, we next have got a contemporary object on our hands which references a well known and loved pop-cultural phenomenon – Pheobe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag. As his book of choice Jed selected Fleabag: The Scriptures, the script to the popular TV show of the same name. Fascinated by the religion-inspired design and inventive writing and motivated by his personal connection to the physical book, he presented us with this breath of contemporary air in the midst of many a book spine falling apart. But: It’ll pass, as the Priest would say.

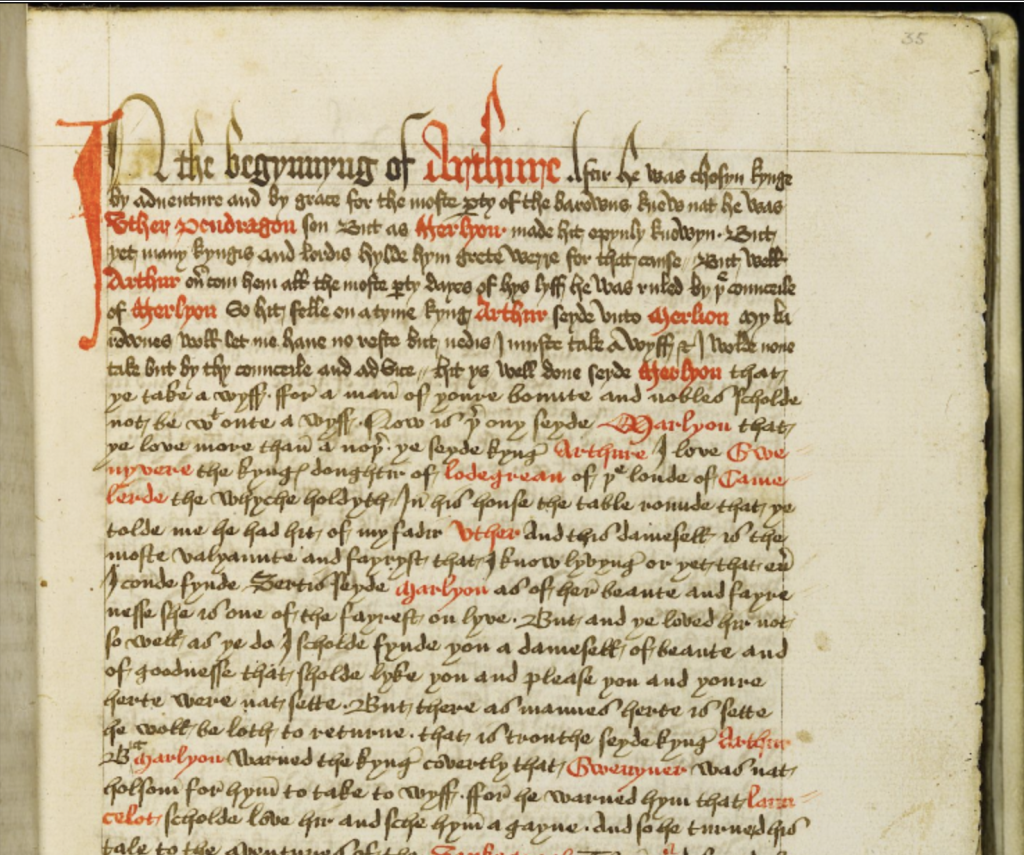

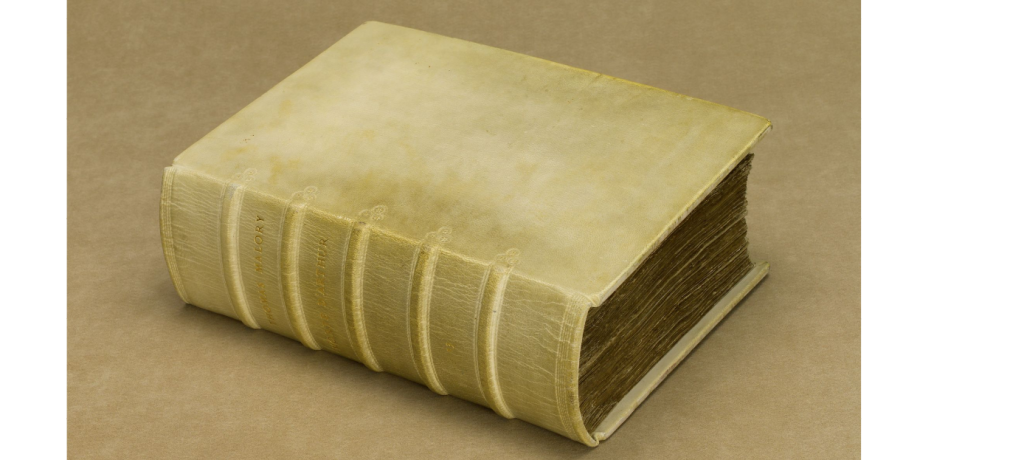

Back on a more historic note we are now looking at Rebecca’s companion in book form and focus point during the first Covid lockdown: her thesis project “Le Morte Darthur” by Thomas Malory. The long read covers the story of the Round Table from King Arthur’s birth to his death. Rebecca explains: “Written by Thomas Malory while in prison, it circulated in the following centuries in print following William Caxton’s edition from 1485. Yet in 1934, a handwritten manuscript, dated around 1471-1483, was found in Winchester College, now known as the “Winchester Manuscript“, British Library Add. MS 59678. All of a sudden, the authoritativeness of the printed edition was called into question by the sometimes stark differences between the manuscript and William Caxton’s edition.” In presenting this particular book, she shared her love for the ways in which this work combines the manuscript and the print tradition in a contested manner. Bringing together different strands of Arthurian tales from the English and French tradition, the book reveals the richness and popularity of these far-travelling tales. Looking back at the first lockdown we experienced not too long ago, Rebecca remembers how these stories allowed her, while being locked up at home, to explore history and fantastical places safely tucked away behind her desk.

Contrasting everyone else’s presentation of a personal physical book, Constance could only bring a verbal account of her favourite book which disappeared into the hands of an anonymous bidder in 2005. The incomplete copies of The Mathematical Collections and Translations (1661, 1665) can be found in many libraries around the world but only a single copy is accompanied by a mass of papers that make up the author’s unfinished biography of Galileo. This copy was owned by the Earls of Macclesfield for more than two hundred years with scholars being denied access to it based on claims that it had gone missing. When the library was auctioned in 2005 it appeared, only to be gone once more. As she has heard much about this mysterious missing copy but was never able to see it, Constance hopes to find a way to rescue it for scholars the next time it will come up for auction. I believe, we all share this hope!

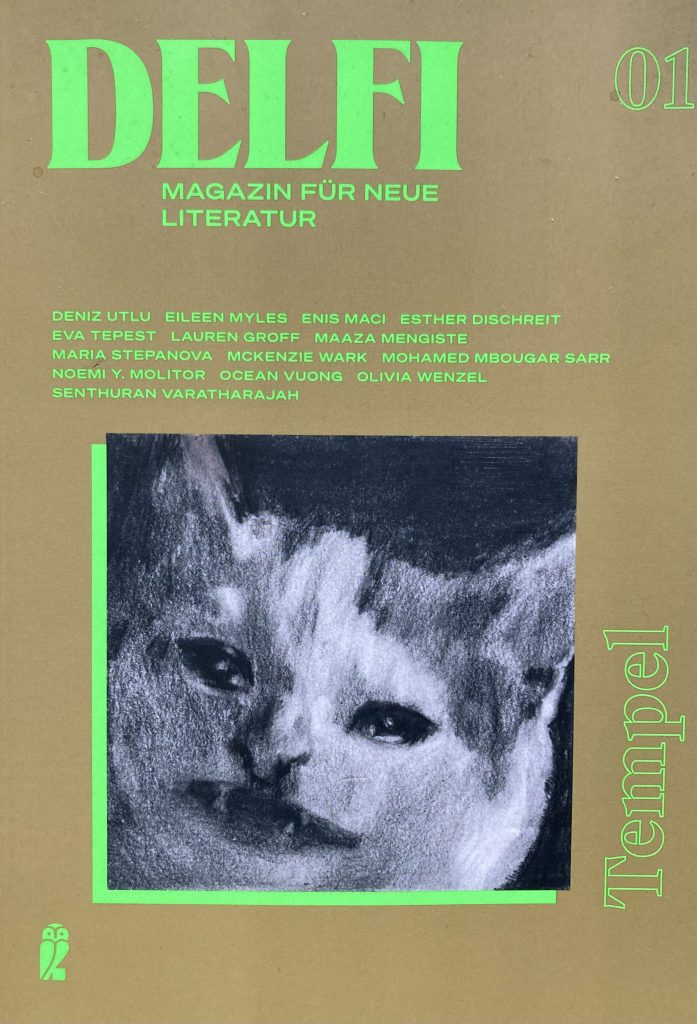

As my personal interests usually lean more towards contemporary issues, I decided to bring one of the few “books” I was able to fit into my suitcase when making my way to Oxford. This September, Ullstein publishing in Berlin published a new magazine for contemporary literature at a moment in time when print magazines seem to be becoming extinct. Uniting literature, pop-culture, and a flashy design the editors think this to be the perfect moment to have faith in the mediums power. While the new Delfi magazine will certainly speak to a specific crowd of interested readers, it also opens the conversation on what traditional commercial publishing houses are willing to publish and support and how profit and the will to foster contemporary literature are in correspondence here. I decided on the magazine as my show and tell as it has been sitting on my nightstand here in Oxford offering moral support through reminding me of my time interning at Ullstein and some great memories made in Berlin at the time.

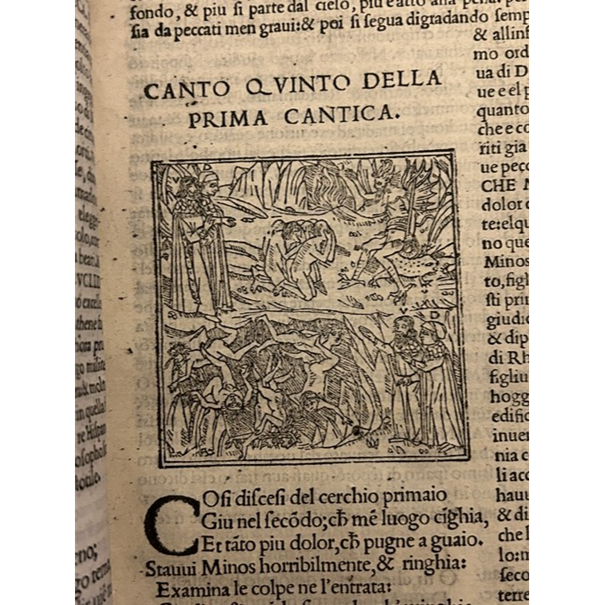

After each student had introduced themselves and their “show and tell” item, we had a close look at some of the Bodleian’s gems and turned delicate old pages with gentle fingers. Fellow student Floride tells me her personal favourite was the copy of the Divine Comedy published in 1529 (ARCH.FOL.IT.1529(1)) which, she says, holds a beauty impossible to resist. Despite the modest scale of the illustrations, the details of the monstrous figures, the intricacies of the sinners’ punishments, and the expressions on their faces—ranging from pain and regret to confusion—are all remarkably discernible. To quote Floride: “It is a testament to how appropriate and attractive illustrations can elevate the reading experience of any book.”

Due to the larger number of students interested in the History of the Book this term, time unfortunately did not allow Prof. Henrike Lähnemann to introduce her own “show and tell” object – will we find out in the course of term?