By Luise Morawetz and Vincent Leung

In the fourth week of our History of the Book methodology module, the topic was palaeography. Dr. Colleen Curran, a researcher at the Faculty of English of the University of Oxford and expert in Insular scripts, took us to the Weston Library’s Visiting Scholar’s Centre to introduce us to the history of scripts. The session included a theoretical as well as a hands-on part, which we will both discuss further in this post to give an impression of the complexity of the topic – and of the joy of working with manuscripts.

Part I

Dr. Curran’s theoretical introduction covered the basics of palaeography that are necessary to explore a manuscript. During the talk, it became obvious that the terminology describing manuscripts is focussed on the practical use and the material side of the object. That shows the difference between being a palaeographer and a literary scientist: While the latter is tasked with looking at the content, palaeography is all about analysing the object. As we will see later on, it is not possible to separate those two dimensions completely. Nonetheless, our introduction started very clearly with the physical dimension by learning about the material – parchment. There, the very vivid designations of the ‘hair’ and ‘flesh’ side are used, Drawing an instant connection to the animal origin. The process of preparing the animal skin was long and challenging but perfected to such an extent that some even managed to peel off one layer of skin to create a second piece of parchment.

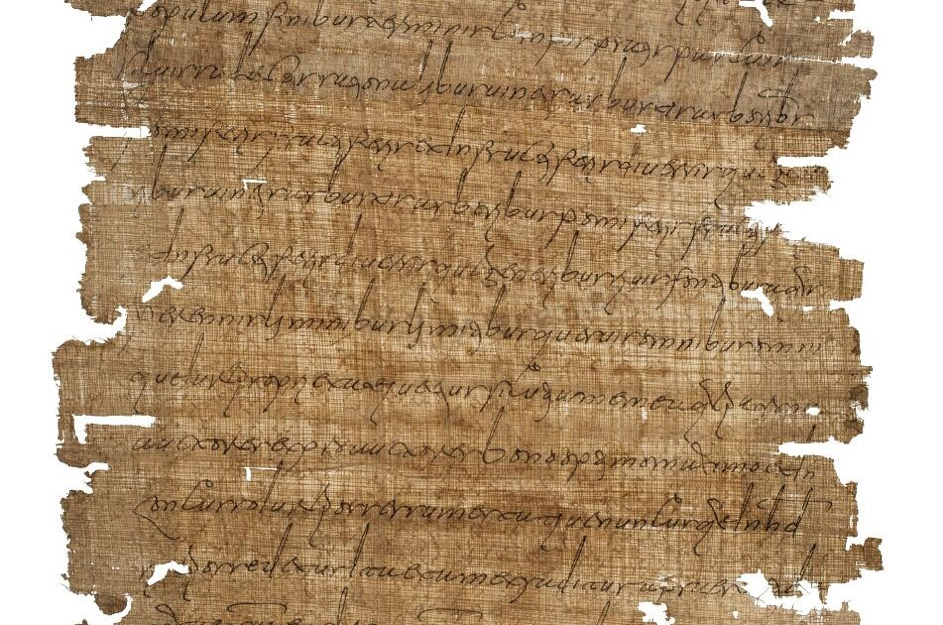

With a quill in one hand, a knife in the other, the scribes were prepared to fill the pages with words before the parchment was folded and sewn together. The knife was used to scrape off misspelt words. The first script Dr. Curran focussed on, was the Old Roman Cursive. It was developed around AD 100, followed by the New Roman cursive approximately a century later. Cursive scripts can already be found very early since they were used in everyday texts. The fast writing did not require a pretty typeface but an easy one, resulting in connected characters.

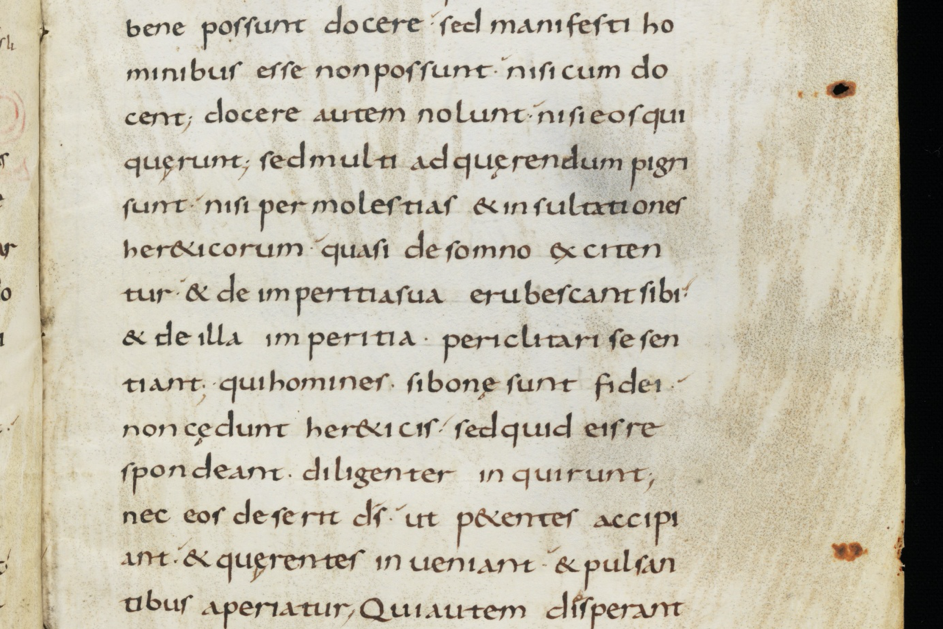

The beautiful writings that we have in mind when thinking about manuscripts, with coloured letters and ornamented initials, occurred much later. They are written in block letters, which required much more concentration and focus of the writer and therefore were used for important and valuable manuscripts. The development of the Carolingian minuscule in the ninth century marked the beginning of the rise of set scripts.

At this time, the value of the written word increased, and therefore an appropriate form to represent the content was needed. Writing every letter out on its own normally produced a very even and legible typeface. Of course, the competence of the scribe had its influence as well. Over approximately two centuries, the Carolingian minuscule was the dominant script. And from there on, the history of scripts got messy. This was due to the fact that, how Dr. Curran made clear, which script was used was at this point mainly a matter of what was in fashion. And as everyone knows, fashion changes fast and almost everyone has their own ideas about it. Therefore, many different scripts were developed, cursive as well as set scripts, each influencing one another. Researchers have done their best to distinguish them and define separate scripts by characteristics like the height of the ascenders or descenders of letters (the parts that are higher or lower than the rest of the letter) or the formation of ligatures (the merging of two letters). How hard it still can be to transfer the theoretical characterisation onto practice, we experienced in the hands-on part of the session.

Part II

As is the case with all forms of visual art and representation, the evolution of script in the Middle Ages was engendered by an interplay of reciprocal stylistic influences, from which a gradual process of written innovation, adoption, and continuous supersession resulted. It is in consideration of these stylistic ruptures and continuities that the act of identifying script necessitates abandoning assumptions of affixed written uniformity and standardisation. Rather, the paleographer is pressed to examine their material, not purely in the context of the greater stylistic trends of its epoch, but also as a living organism, mirroring variable degrees of mutability and individuality set forth by the very hand(s) of its scribe(s). As this post will demonstrate, only through desisting from rigid formulations of categorisation can the paleographical method extract the maximum quantity of information apropos of provenance, cultural appurtenance, and stylistic evolution.

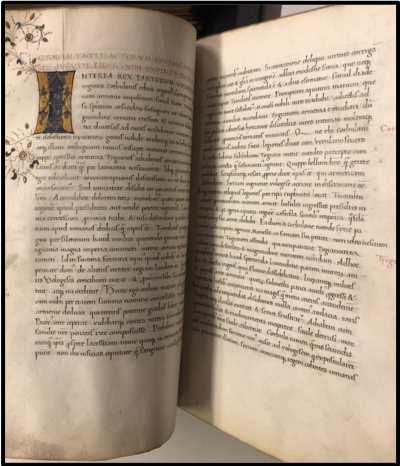

Thus was the scrutinous nature of our hands-on task in the fourth week of our History of the Book methodology module. Following Dr. Curran’s informative outline of the development of scripts from the first to fifteenth century, we were subsequently divided into pairs, posed in front of a medieval incunable or manuscript, and given ten minutes to identify the script employed therein.

Working with Lena Zlock (MSt Candidate, Magdalen College), we began by firstly determining whether the article was printed or handwritten. Upon constating the presence of written deviation between identical letterforms, we quickly arrived at the determination that the article treated was, in effect, a handwritten manuscript. Drawing on our now bountiful knowledge of the quattrocentesco written script tradition (grâce à Dr. Curran), we were now posed to avert our attention to the identification of script, in the knowledge that our text would adhere perfectly and incontournably to the greater trends of its epoch; that there was no way—absolutely none whatsoever—that individual and localised tastes would come to present gradual stylistic ruptures, resulting in the very evolutions we were studying. For after all, medieval scripts were remarkably stable up until a certain point in which visual trends were introduced and adopted seemingly overnight—correct? Such nescient paleographic lambs as we were.

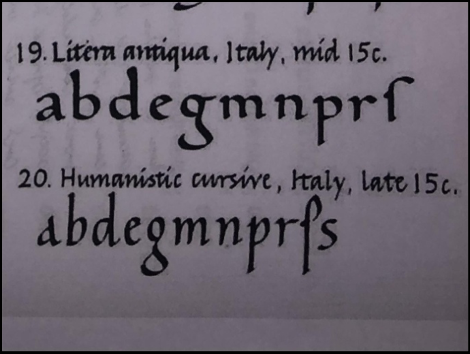

Our expectations of written standardisation would come to present more questions than answers, as we soon noted that the manuscript concurrently incorporated elements of both mid fifteenth century Litera Antiqua and late fifteenth century humanistic cursive. The two scripts are remarkably similar, save for three key visual innovations of the latter: the prominent presence of descenders in the long s form (ſ), the unarched ‘ɑ’, and the close looped ‘g’. Whereas the manuscript presented before us lacked the former two elements, it did, however, incorporate the closed ‘g’ throughout. Ensnared between two scripts, visually analogous to one another, would

we ever arrive at a definitive determination? Spoiler: we wouldn’t. Inferring to the best of our abilities with careful consideration of the elements presented before us, we declared that it was

an exemplar of Litera Antiqua, the closed looped ‘g’ simply representing an individual stylistic adoption prefiguring its wider use in the later written conventions of the fifteenth century. Surprisingly, we hit the mark. We had done it. We had done a palaeography. Moreover, we had achieved this feat all by ourselves (as mercifully, we were permitted to refer back to a visual table of scripts provided by Dr. Curran). Elated but not rendered complacent in our accomplishment, we returned back to our individual colleges, set up our workspaces, and proceeded to waste the entire evening perusing Oxfess.

The lesson then, dear reader, is plain. For it is only through a critical awareness of the representational malleability of scripts that one can avoid misidentification, allowing us furthermore to place a script within the context of the greater stylistic trends of its epoch.