‘15cBooktrade’ and what we can learn from it

The printed book now lying in front of me – an edition of Otto von Passau’s ‘Die vierundczweinczig Altê. od’ d’ guldin tron’ from the year 1480 – has travelled a long way before arriving here, on a wooden table in Lecture Room 2 of the Taylor Institution, Oxford, on a rainy day at the end of October 2019. The copy changed hands a number of times; it travelled from one owner to another, and from one library to the next; it even changed countries and travelled from Germany to England, where it is still kept in the archives of the Taylorian Library, safely packed in a small cardboard box.

Opening a medieval printed book can be a decidedly sensuous experience; and working with one can come very close to the idea of a detective in hope of reconstructing past events. Except the material evidence of the crime scene does not (usually) involve blood, but the material traces left behind in the books: these may e.g. include a colophon and an ex libris, the typographical format, handwritten corrections on the margins, supplements and collation, scribbled comments by a later user or other reading marks. Based on the material evidence in the book, one can hope to unravel some of its past and gain information on its significance as a cultural object.

The recently completed project ‘15cBooktrade’ (2014–2019), directed by Prof. Cristina Dondi at the University of Oxford, undertook the task of collecting and bringing together material and bibliographical information of early printed books between the years 1450 to 1500. Of these early volumes, known as incunabula, 30,000 editions can be identified today, which have survived in ca. 450,000 copies, located in approximately 4,000 libraries around Europe and North America. The aim was first and foremost to create a digital platform for gathering the material and bibliographical information of the surviving as well as missing incunabula and provide the digital tools to analyse them. For this purpose, the project created a database called MEI, short for ‘Material Evidence in Incunabula’, which collects data on bibliographical and material evidence, such as ownership, binding, decoration, manuscript annotations, reading marks, corrections or comments.

One of the immediate benefits of the MEI-database is its inclusion of different information. Thus, the MEI also incorporates other satellite databases, such as the database ‘Owners of Incunabula’, which gathers more detailed biographical information on former and present owners of the printed books. Thus, the input mask not only allows to search the database for a specific edition or work, but also to search for the owner of a copy; other facets which can be searched for include the profession as well as gender of the owner, the author of a work, or the holding institution of a copy. These newly gained information can lead to intriguing questions, which would never have arisen in the first place, had it not been for the collection and concentration of data in one database. These questions could include the following: Which works did a clerical person possess in the second half of the 15th century? From whom did he or she receive their copies? And from where? What was the role of the female reader- and ownership? How did it change over time? Were there any women who possessed copies of Otto von Passau’s work? (Yes!). But also: What was the market value of a medieval print? How did its price compare to the price of, say, a chicken? These latter questions can now also be addressed thoroughly thanks to the close analysis of a unique manuscript called ‘Zornale’, a day-book of Francesco de Madiis, recording the daily sails in his Venetian bookshop over a time period of four years.

By gathering all these data, the project ‘15cBooktrade’ enables us to look for the social and cultural impact the onset of print had on late medieval and early modern society in the second half of the 15th century. Each edition can unravel a bit more about its social and cultural ‘Sitz im Leben’.

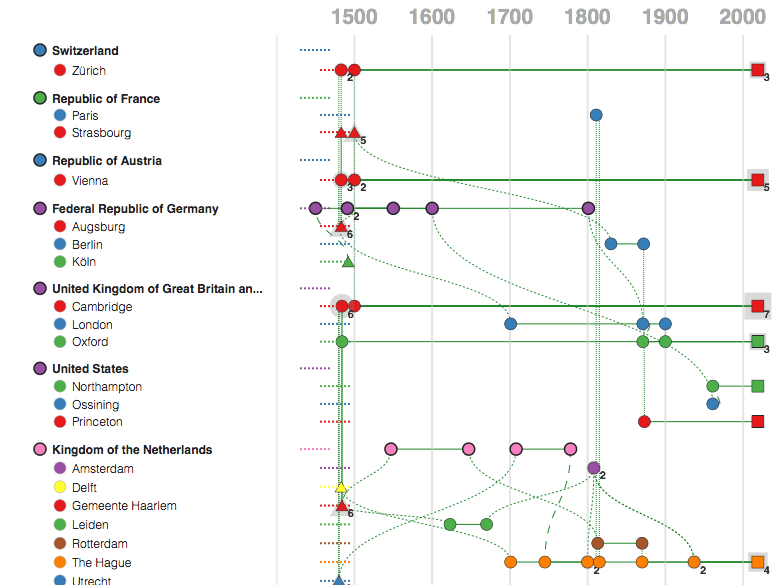

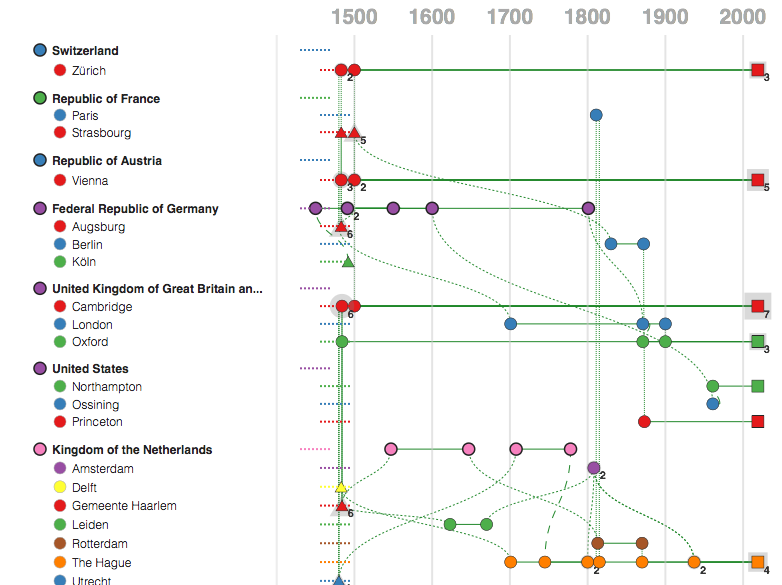

One of the project’s most intriguing features not mentioned so far is the visualisation tool ‘15cV’: this allows us to retrace the history of a specific copy of a work by mapping its journey through space and time, that is translating the history of its ownership by specific persons or holding institutions into visual data. This way, networks between different copies and movements of a specific copy from one library, city, or country to another can become obvious to the user in a moment. What took many hours, days and perhaps weeks before, can now be comfortably done in the split of a second.

The results for the search entry ‘Otto von Passau’ (author) and ‘Die vierundzwanzig Alten, oder Der goldene Thron’ (title) provides information on the provenance and journey of the printed editions, which survive in various copies in European and North American libraries, see online as well: http//15cv.trade.

The results for the search entry ‘Otto von Passau’ (author) and ‘Die vierundzwanzig Alten, oder Der goldene Thron’ (title) provides information on the provenance and journey of the printed editions, which survive in various copies in European and North American libraries, see online as well: http//15cv.trade.

And the best news of all: these tools can be used – for free! – by anyone, be it a researcher, student or simply a person interested in the history of books, in the story they have to tell, and in the roads these books have taken to get here.

1 thought on “The road goes ever on and on”