by Eva Neufeind

At the beginning of December 2020, I was accepted to spend Hilary Term 2021 as an intern for Henrike Lähnemann, professor for German Medieval Studies at the University of Oxford. The connection between Henrike Lähnemann and me was established by Professor Eva Schlotheuber (Düsseldorf), who suggested it would be fruitful to learn more about the use of the Digital Humanities. – No sooner said than done! I set off to Oxford to experience the city in times of a pandemic, dive into the possibilities of the Digital Humanities and develop a sheer endless fascination with St Edmund Hall, the college I was staying at.

When I arrived in Oxford on January 11th, I could only sneak a brief peak at the brilliant architecture and atmosphere of the city before I had to quarantine for ten days. Fortunately, I was supplied with a wide selection of books, ranging from the notorious Oxford detective stories to monographs on the history of Oxford University and St Edmund Hall.

During my first week in Oxford, my fellow intern Agnes Hilger and I were (virtually) introduced to the Enclosure Group, which is an interdisciplinary project about women in enclosure in art and history. Attending the group’s sessions was enjoyable; becoming aware of the different contexts of enclosure as well as listening to truly intriguing discussions was inspirational. Besides enjoying the thematic approach, Agnes and I had a great time setting up a new blog for the Enclosure Group. Planning a website, discussing its aesthetics and user-friendliness, and eventually seeing it come to life was a truly exciting task.

An important aspect of my time as an intern was working with digital editions. For the first time, I came into contact with this topic through the brilliant Taylorian video course on Digital Editions by Emma Huber, the librarian responsible for the project. In this series, Emma gives an introduction to creating a digitised edition. It covers a wide-range of topics from transcribing a manuscript to encoding it with XML in a code editor as well as proof-reading.

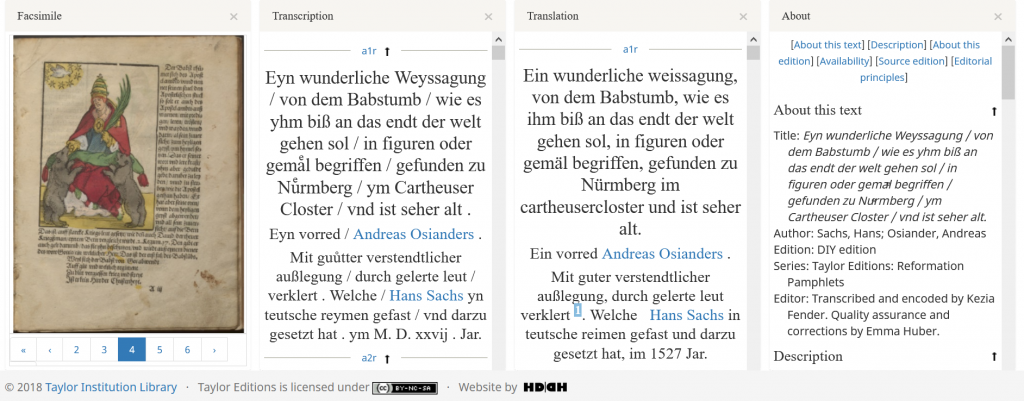

The proof-reading of the Reformation pamphlet “Eyn wunderliche Weyssagung: a digital edition” gave me a detailed idea of what a digital edition looks like. The columns are interconnected. For example, clicking on the page reference (e.g. a2r) automatically shows the correct manuscript page. Having a closer look at digital editions instantly convinced me of the great advantages of transcribing and encoding manuscripts. This technique requires the editor to pay close attention to the manuscript and find convenient ways to encode special characters. Also, correcting and annotating the edition is a matter of seconds.

After having acquired a basic idea of digital editing, Agnes and I had to decide on a manuscript to encode for the History of Book seminar. In the German Graduate Seminar we were introduced to the Reisebericht (MS. Bodley 972) by Arnold von Harff. In this travel account, Arnold describes his pilgrimage from Cologne to Jerusalem. Besides talking about the journey actually took, there is also a notable amount of information that was clearly taken from older reports (e.g. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville). Episodes Arnold certainly did not experience himself were his travels to Arabia and, obviously, his encounter with dog-headed people. The genre of medieval and early modern travel literature was not intended to be used as actual travel guides, but served the purpose of entertaining the readers and allowing them to go on an imaginary journey in their mind.

Not only did Arnold take the seminar’s participants onto a mental pilgrimage, but his travel account also appealed to Agnes and me as perfect to be encoded. The Bodleian Library acquired the manuscript in 1813 from Karl Etter, who was a mineralogist in St. Petersburg. – Not only is the story of how MS. Bodley 972 came to Oxford extraordinary, but also the composition of the edition, which is a mixture of hand-drawn pictures and print is intriguing to examine. In a session of the History of the Book seminar, Agnes and I had a chance to take a closer look at the manuscript. Andrew Dunning, one of the manuscript curators at the Bodleian Library, turned the pages for us. Probably inspired by the work of the Merton’s Beasts project, I was very interested in seeing the depiction of animals in Arnold’s manuscript. Especially when looking at the way the drawings are scaled or adjusted to the text, it becomes apparent that the images were added to the manuscript after the text was finished. Looking at the materiality as well as the connection between the texts and drawings was giving me new insights into book history.

I became even more aware of the book as an object when Agnes and I had the chance to attend a workshop at the Bibliographical Press of the Bodleian Library in which we learnt more about the process of printing. To actually put type together and use a printing press was an experience that made me more aware of materiality and how many different things are needed to produce a book. I highly recommend checking out Agnes’ blog post on type-setting. In a follow-up blogpost, I wrote about my first experience using an Albion printing press.

Lastly, I would like to talk about St Edmund Hall, a place I got a lot of comfort from. In her novel “Gaudy Night”, the author Dorothy L. Sayers wrote: “It is said that love and a cough cannot be hid.” – After I got myself quite a lot of Teddy Hall merchandise and had a worrying number of conversations on the history and the culture of this college, this quotation by Sayers got stuck in my head and I questioned why I became such a Teddy Hall supporter in the first place: I spent a lot of time reading about the history of the college. One of my favourite interests are proto-reformation movements, i.e. Lollards and Hussites. Learning that two of the former principals of St Edmund Hall, William Taylor and Peter Payne, were avowed Lollards, naturally sparked great excitement in me. Especially Payne, who escaped to Bohemia in 1415, highlighted the connection and cultural transfer between England and Bohemia. To help retrace Payne’s path of life , I started translating the work Husitství a Cizina [= Hussites and foreign lands] by František Michálek Bartoš from Czech to English. – Of course, there are many more thrilling aspects about the history of the Hall that would deserve to be covered, but the Lollards are a great example of why I think the Hall is appealing from a historian’s perspective.

Another important part of my fascination for St Edmund Hall certainly developed because of the people I have met here. During non-pandemic terms, it is common to rush from one place to another to attend seminars and meetings, have one-time encounters with several people and hardly get to know flatmates. These days, most events are only a few clicks away and also flatmates are much more present. I can call myself endlessly lucky for the accommodation I stayed at for the past nine weeks. Everyone was understanding and supportive, scones and cakes were shared and I got to learn so many different things in extended small talk. As we were all working on different subjects, the kitchen would sometimes turn into a little interdisciplinary classroom. I appreciated that a lot! Also, consulting the library, browsing through the books and always having people around who were happy to help was a great experience. Teddy Hall advertises itself to have a “friendly and relaxed atmosphere”, and from the time I have spent here I can wholeheartedly confirm this.

In a final step, the only thing I can do is to say thank you to Henrike Lähnemann for making this great time possible for me and showing me a whole new perspective on editions, books, printing, and so much more.

And, of course: Floreat aula!