Impressions from my work as an Erasmus intern at the University of Oxford

Agnes Hilger

At the end of 2020, the UK did not only leave the EU but also the Erasmus programme. Despite of that, I was accepted for an Erasmus internship for Hilary Term 2021 with Prof. Henrike Lähnemann, who introduced me to all of her students and colleagues as “the last of her kind”. In this blogpost, I report on a weird and wonderful time: an Oxford trimester in lockdown, my courses, projects, and experiences at the intersection of Medieval German Studies and Digital Humanities.

First-time visitors to Oxford usually head for the Radcliffe Camera, the Sheldonian Theatre, the Bodleian library. Harry Potter fans visit New College or Christ Church first of all. When I arrived on the 4th of January, I did none of this. Instead, I spent the first ten days in my room in Iffley Road – self-isolating. On the 6th of January, the new national lockdown was announced.

My original plans (attending in-person teaching, stroking medieval manuscripts in the library during the day, meeting Oxford students in the pub in the evening) were now a thing of the past.

Instead of learning every little detail of Codex Taylor Institution Library MS. 8° G.2., a 15th-century manuscript of Bruder Philipps “Marienleben”, I learned that staying flexible is everything. The ‘History of the Book’ course I was invited to attend this term, for example, had moved online, offering to work on the high-quality digitized versions.

But medievalists share a strange fascination: touching manuscripts. Not content only to read the texts, they also want to turn pages, to hold the codex in their hands. This fascination is cultivated – with a simultaneous fascination for the possibilities of digitization – in the History of the Book course. The course usually takes place in different libraries around Oxford. Manuscripts are examined and edited, in cooperation with a Digital Editions Course at the Taylorian. What to do when the course itself has to take place digitally?

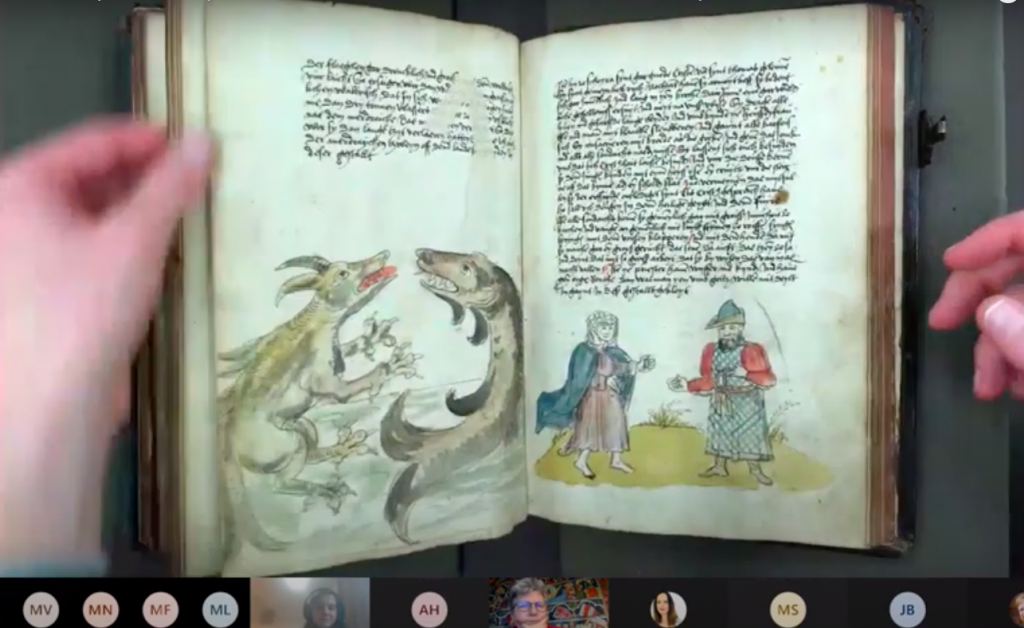

We could not hold the manuscripts ourselves but at least we were allowed to watch Andrew Dunning, one of the manuscript curators at the Bodleian Library, turn the pages for us, week after week. I was particularly interested in MS. Bodley 972, a manuscript from the 16th century – that means from a time when printing had become the default form of book production, turning manuscripts into something of a curiosity for connoisseurs. Together with my fellow intern Eva Neufeind, I started creating an edition of this manuscript which is particularly striking through its pen-and-wash drawings. While transcribing, I stumbled across a passage in the digital copy which looked as if someone had stuck white tape on it. Andrew explained that this was a later paper repair, from the 19th or 20th century, visible in the screenshot above.

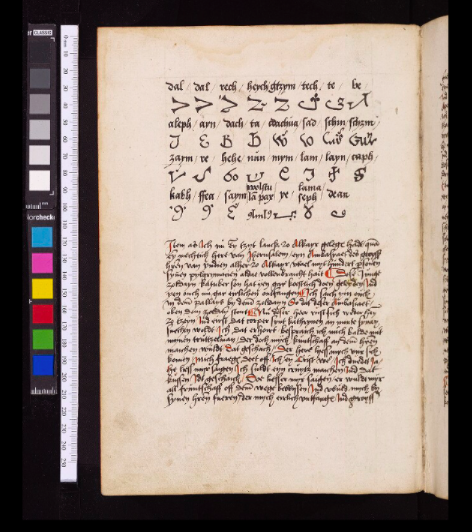

Such passages, which are a bit more difficult to transcribe, are not the biggest challenges when working on digital editions. While I had worked on digital edition projects before, I have never been responsible for so many things at once. MS. Bodl. 972 is a manuscript of the Reisebericht of the knight Arnold von Harff who describes a three-year pilgrimage. He includes alphabets of various languages, which are hard to transcribe as text and in characters simply not known to me as a German-speaking medievalist. And the characters used elsewhere by the scribe also present difficulties. Letters at the end of a word, for example, are often abbreviated to a downstroke of the previous letter. It took a few email exchanges (subject: “weird abbreviations”) with Emma Huber, the librarian responsible for the project, until it was reasonably clear how this could be rendered in a transcription.

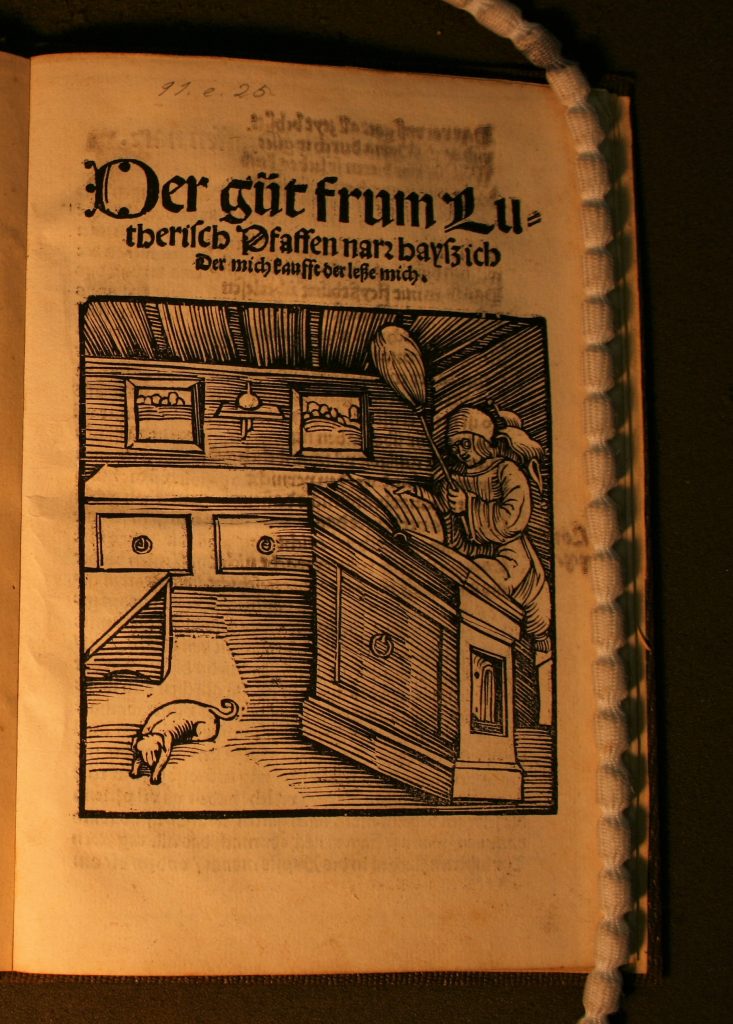

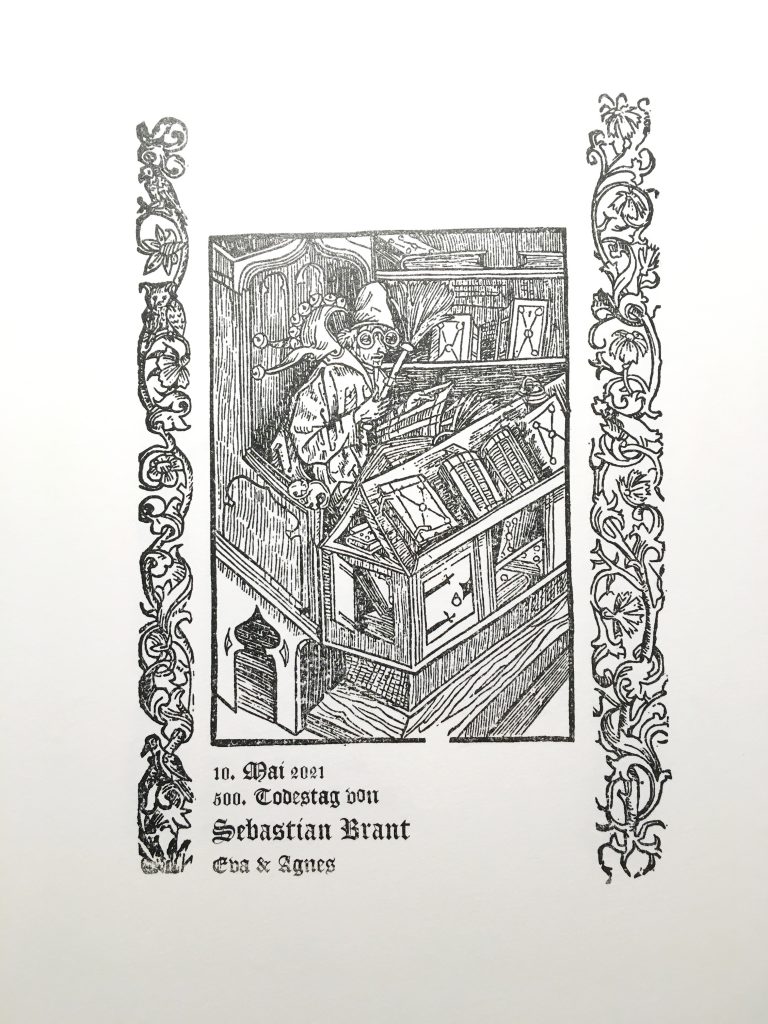

Another of my Oxford projects was similar – and yet quite different. This is also a digital edition on which I am working together with the PhD student (and Oxford alumna) Alyssa Steiner which will later be available as a Taylor Edition, editing a Reformation pamphlet: ARCH.8o.G.1521(27), entitled “Pfaffennarr”, a print edition which recycles the woodcut of the ‘book fool’ from Sebastian Brant’s Narrenschiff as title image and uses it to mock Catholic clergy. Here, there is little difficulty in transcribing and the text is quite short. We have decided to take this project further: In addition to the diplomatic transcription (an exact transcription of the characters of the original), we also want to provide a normalized text and a commentary – Alyssa is also trying to provide a translation into English. If everything goes well, the edition will be ready in time for the 10th of May this year, the 500th anniversary of Sebastian Brant’s death.

And a workshop at the Bibliographical Press of the Bodleian Library was also dedicated to this anniversary. Together with my fellow intern Eva, I was allowed to print an anniversary card in an old printing press – if you want to call it that to commemorate a death day. Gutenberg’s invention is universally known as a turning point in the history of the book which now no longer had to be copied line by line but could be reproduced thousands of times. I had not realised until this hands-on experience just how much work this still involves: type-setting and operating the press alone take time and require patience – even though the 19th century press we used is certainly easier to operate than Gutenberg’s.

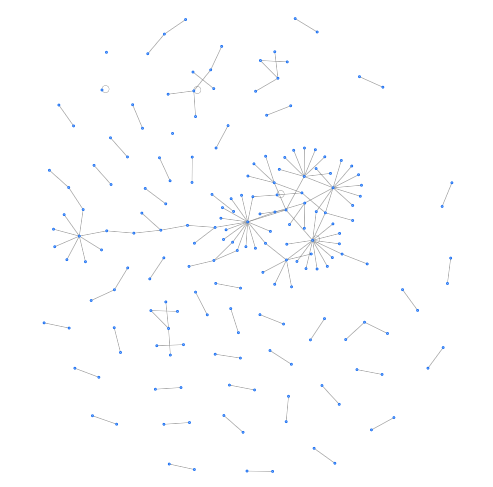

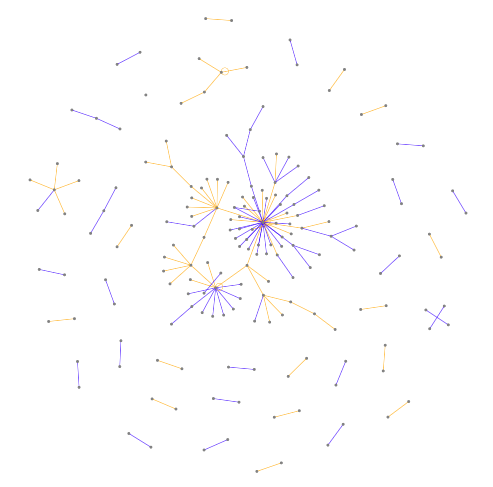

My final project had little to do with craftsmanship and, at least as far as I was involved, only tangentially with old manuscripts. Since 2016, Henrike Lähnemann and the historian Eva Schlotheuber (Düsseldorf) have been editing the ‘Lüner Briefe’, a collection of letters written by the nuns of the Lüne reform monastery, which tell us about the nuns’ networking. As a digital humanist, I naturally imagined the ‘network of nuns’ to be a graph with nodes and edges. Although not all the letter data has been collected yet, I tried my hand at some initial visualizations and prepared the data as a network using a Python script. These networks still have their flaws, especially since many letters are anonymous. Nevertheless, the network already makes a few things visible that can give me as an outsider some interesting insights. For example, many connections come from and go to the prioresses Sophia von Bodenteich and Mechthild Wilde. This leads me to the assumption that they played an important role in the ‘nuns’ network’.

And not only are the nuns more “connected” after my stay but – and I apologize for the metaphorical leap – so am I. Thanks to a shared kitchen at Exeter House and occasional walks in various constellations, not all of my Oxford contacts are purely digital. And so I can only repeat what probably every student who has ever taken part in the Erasmus+ programme will report back: the value of this experience, personally and professionally. Here is to hoping that there even after the end of the participation of the UK in the programme, there will be other ways to keeping the fruitful exchange alive, digitally and in-person!

********

Agnes Hilger studies German literature, History, and Digital Humanities at the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg, where she has worked as a student research assistant in the project on the beginnings of modern poetry, in the Narragonien Digital project, and in a digital edition project on Konrad von Fußesbrunnen’s Kindheit Jesu. In Hilary term 2021, Agnes Hilger was an Erasmus intern at the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, University of Oxford.