Update 1 Dec 2023: The published ‘Monk-Calf’ and the complementing ‘Nuns on the Run’ are now available in ebook format and as digital editions: https://historyofthebook.mml.ox.ac.uk/reformation-pamphlets-from-1523/

Exhibition held in the Voltaire Room, Taylor Institution Library, Oxford University, 9 June to 26 June 2023. Launch on 16 June 2023, 5pm. The exhibition has grown out of the collaboration of students from the MSt in Modern Languages who edited the German and French pamphlets as part of the ‘History of the Book’ Method Option, one intern, Elena Trowsdale, from the MSc in Digital Scholarship with Emma Huber at the Taylorian who edited the English pamphlet, and an Art History intern from Hamburg University, Anja Peters, with Henrike Lähnemann. The two interns co-curated the edition which launches also the edition of the three early modern pamphlets in the Taylor Institution Library’s Reformation Pamphlets series. Thanks go to the librarians of New College which holds the French pamphlet, to the Bodleian Library which holds the English pamphlet, to Clare Hills-Nova for the Artists Book, to James Howarth for the loan of the beakhead, to Wes Williams for his advice on early modern monsters, to Jim Harris for opening the Ashmolean print room treasures, and to the whole team at the Taylor Institution Library for their help and support.

Display Case 1: The Monk Calf and Pope Donkey pamphlets

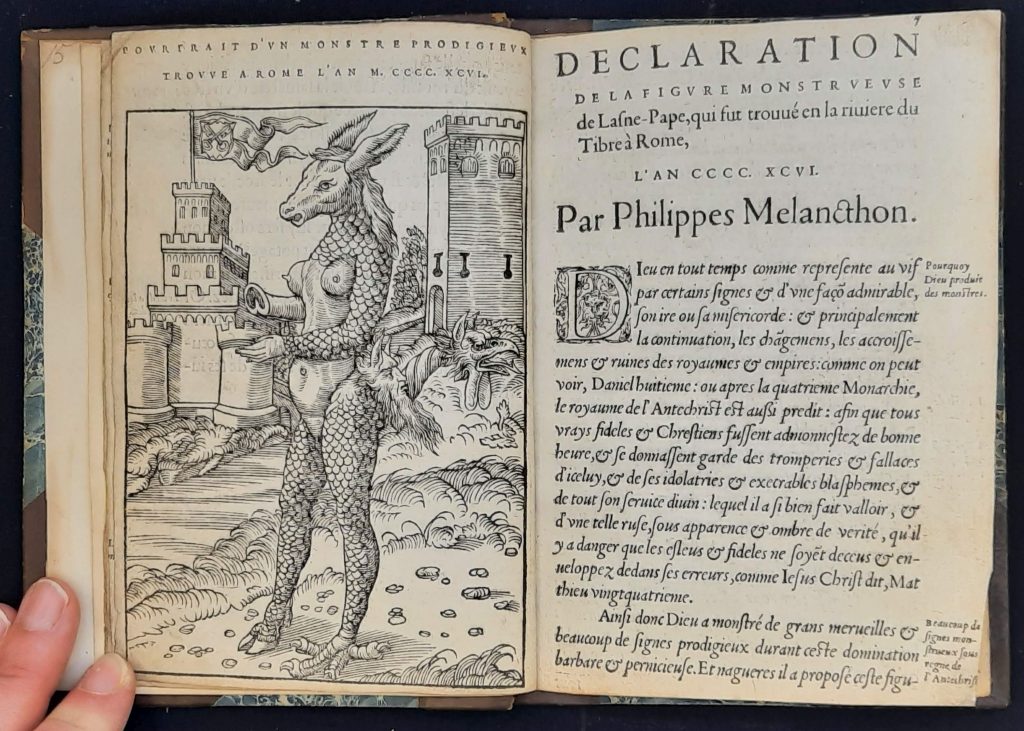

During the 16th century, images of unusual natural phenomena including ‘monstrous’ human or animal misbirths were increasingly published in popular prints, broadsheets and pamphlets and thus made available to a wide audience across much of Europe. They were often accompanied by colourful descriptions and interpretations of their meanings, which led people to believe that these accumulating deviations from the natural order might be signs of warning and omens from god, or even harbingers of the end times. What exactly these monstrous births were presaging and what or whom they were warning against could vary, depending on who was interpreting them. The same phenomenon could be read to mean completely opposite things, to align with the agendas of different authors. Martin Luther (1483–1546) and his followers in the Reformation frequently utilised such monsters to make polemic arguments against the Catholic Church, the papacy and the monastic orders. The two pamphlets displayed in this first case [1, 2] along with their French and English translations [3, 4] describe the Monk Calf and the Pope Donkey. They were written by Martin Luther and prominent theologian and reformer Philip Melanchton (1497–1560), published together in 1523.

- Martin Luther, ‘Deuttung der grewlichen figur des Munchkalbs tzu Freyberg in Meyssen gfunden’ (Erfurt, 1523).

Oxford, Taylor Institution Library, ARCH.8o.G.1523(8), ed. by Katarina Ristic

The so-called Monk Calf was born to a cow near Freiberg in Saxony on 8 December 1522. It had a bald patch with two horny knobs on the head, a lolling tongue and only one eye. A skin flap on the back that was said to resemble a cowl, along with its “tonsure”, lead to its name. According to Luther’s interpretation, the Monk Calf showed the true nature of the monks and the monastic orders. He explicates every detail of the calf’s appearance and its meaning. That God has put a calf in the habit of a monk signifies that monasticism is nothing more than an outwardly display of holiness, hiding ‘the false idol in their deceitful hearts’. The tongue shows that the teachings of the monks are idle gossip, the tightly wound cowl their stubbornness.

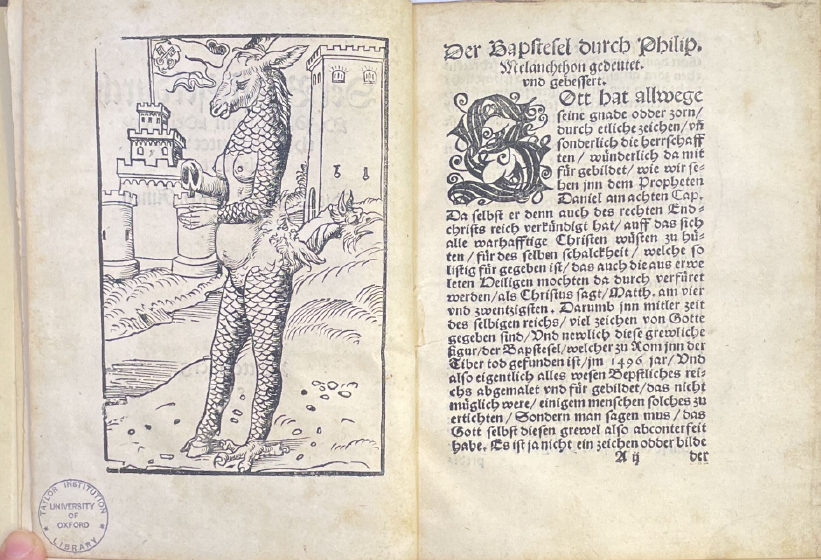

- Philip Melanchthon and Martin Luther, ‘Der BapstEsel durch M. Philippum Melanchthon gedeutet vnd gebessert. Mit D. Mart. Luth. Amen.’ (Wittenberg: Nickel Schirlentz, 1535).

Oxford, Taylor Institution Library, ARCH.8o.G.1535(9)

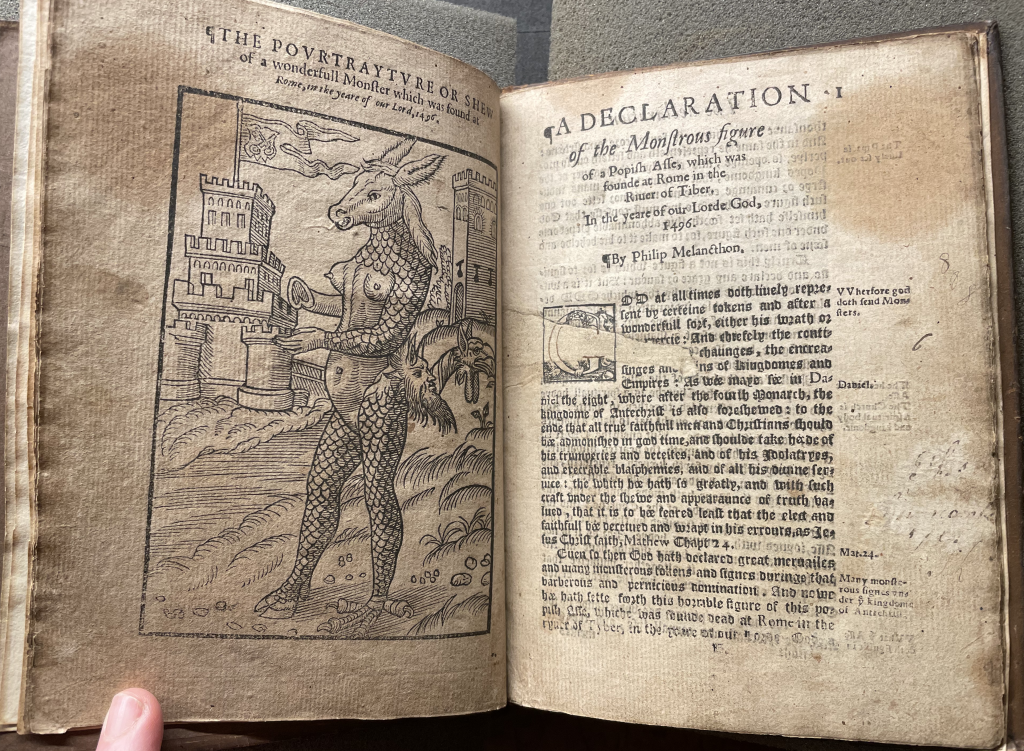

The Pope Donkey, or Papal Ass, was allegedly a monster found in the Tiber near Rome in 1496. Its more grotesque features suggest that it might have been an invention rather than a real malformed animal, made up in Italy at the end of the 15th century for the sake of exploiting it for political polemic directed against pope Alexander VI. It has the head of an ass, a female human torso, scaly arms and legs (one of them ending in a hoof, the other in a claw) and a dragon-like tail. Melanchton saw the whole creature as a symbol of the papacy, with the ass head representing the pope. He had published his interpretation of the Pope Donkey before, which he republished at Luther’s instigation alongside the Monk Calf.

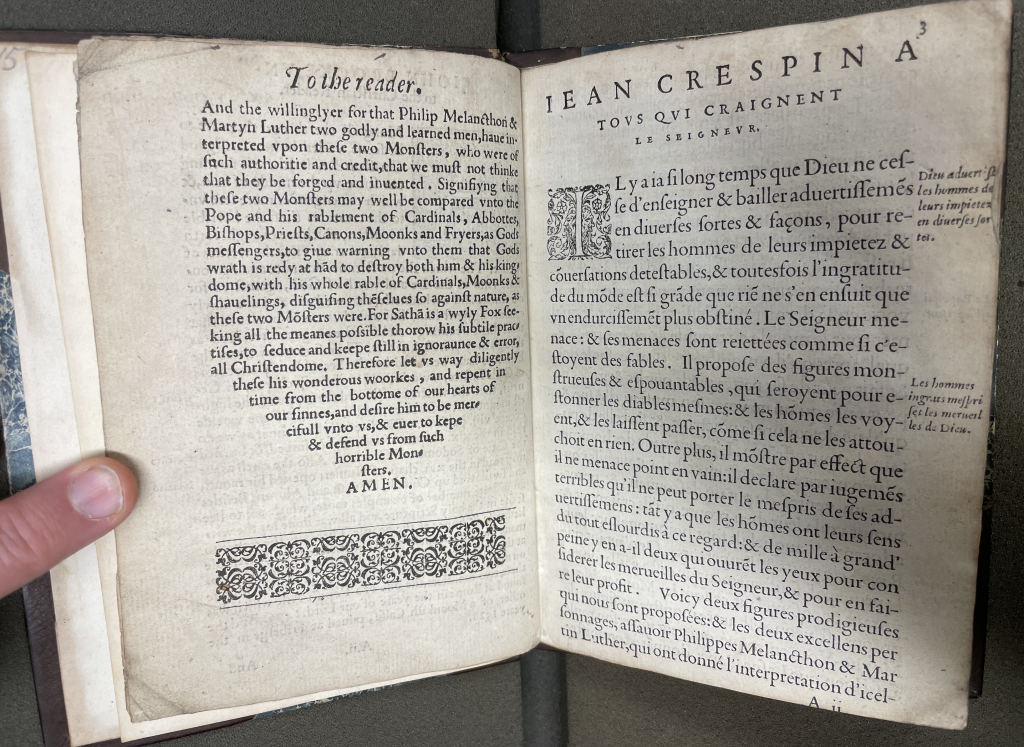

The two pamphlets were very successful and got reprinted several times, as well as translated into different languages. The English translation by John Brooke [4] was done after the French version from 1557 [3].

3. Philip Melanchthon and Martin Luther, ‘De Deux Montres Prodigieux […]’ (Genève, 1557). Edition of the moon calf part by Ksenia Dugæva as part of the Taylor Editions.

Image: New College Library, BT1.17.6(1)

The preface by John Brooke ‘To the reader’ bound into the New College copy which calls for repentance to be defended “from such horrible monsters”, followed by the preface by the French translator.

4. Martin Luther, Philip Melanchthon, and John Brooke of Ashe, ‘Of two woonderful popish monsters, to wyt, of a popish asse … and of a moonkish calfe. Witnessed the one by P. Melanchthon, the other by M. Luther. Tr. by John of Ashe Brooke […]’ (London, 1579). Oxford, Bodleian Library, Douce B subt. 268

In his interpretative commentary on the Pope Donkey [2, 3, 4], Philip Melanchthon compares its scaled body to that of the Leviathan, as it is described in the book of Job (chapter 41). Like the biblical serpent, the donkey has shield-like scales that are joined tightly together so that nothing can come between them. This signifies how the princes and great lords of the world are tied to the pope, protecting him and his “barberous, and tyrannicall kingdome” as the English translation puts it.

- Abraham Bosse, with creative input from Thomas Hobbes, Frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’ ‘Leviathan‘ (London, 1651).

Printed; accessed from Wikimedia Commons.

Display Case 2: Mooncalves

The word ‘mooncalf’, or in German ‘Mondkalb’ was used in the 16th century to describe monstrous births, whose malformities were superstitiously attributed to the sinister influence of the moon. It was normally used for the abortive fetuses of farm animals like cows or sheep, but sometimes applied to human misbirths as well. Luther uses the word on several occasions in his works, and although it is not mentioned in the Monk Calf and Pope Donkey pamphlets, the similarity of the words mooncalf and monk calf is noticeable. By definition, the Monk Calf of Freiberg was a mooncalf.

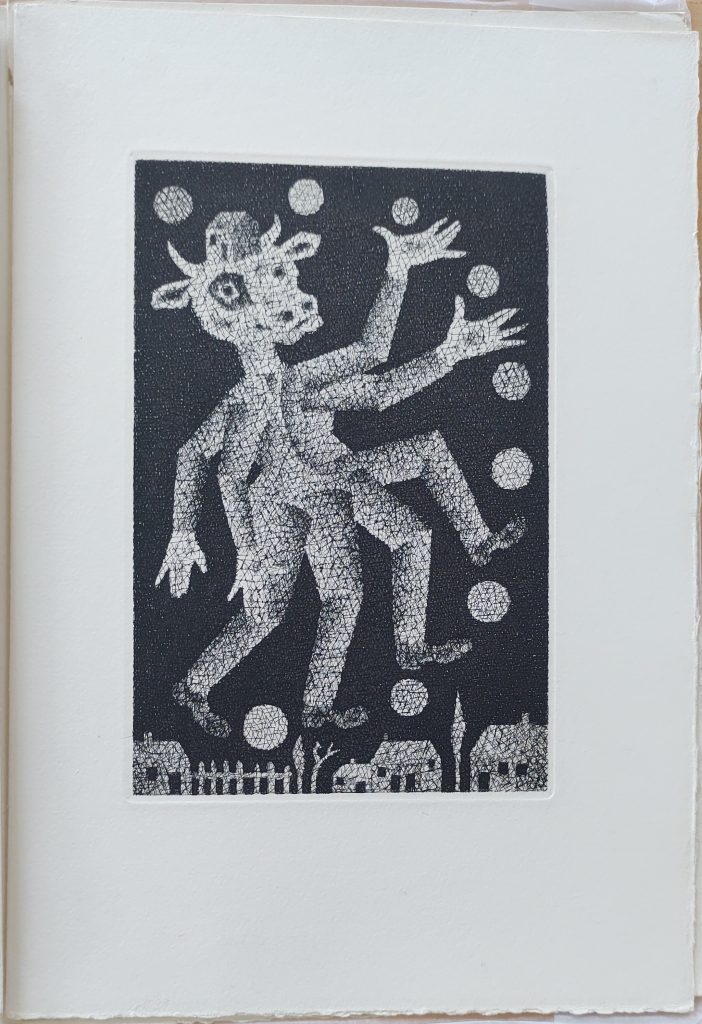

The word was also used as an insult referring to an ugly, dumb or gullible person. In this way it is mentioned by William Shakespeare in his play The Tempest (c. 1610–11), when Stephano speaks to the monstrous Caliban: “Moon-calf, speak once in thy life, if thou beest a good moon-calf.” (Act III, Scene II). Displayed in the case is an illustration by Léonor Fini showing Caliban and the spirit Ariel [1].

The lithograph is part of an artists’ book, or livre d’artiste, from the W.J. Strachan Collection housed in the Art, Archaeology and Ancient World Library. Artists’ books are an originally typically French artform, in which a text by a French or foreign author is illustrated by an artist and published in mostly very small numbers. They are objects of collaboration between multiple people, including the author, illustrator, typesetter, printer and publisher. The collection that includes works by famous 20th century artists such as Kandinsky, Matisse, Dalì and Picasso, as well as lesser-known artists, was donated to the Taylor Institution Library by Walter J. Strachan, a teacher of modern languages at Bishop’s Stortford College. He had spent a large part of his career amassing his collection during frequent visits to Paris.

- Léonor Fini, Illustration to William Shakespeare [Translated by A. Du Couchet]; ‘La Tempête’ (Paris, 1965), Litograph; 40 x 29 cm.

Oxford, Art, Archaeology & Ancient World Library, STRACHAN.95 - Mario Avati, Illustration to Lewis Carroll, [translated by B. Citroën]; ‘Chiméra. Deux contes photographiques’, (Paris, 1955); Etching; 28 x [?] cm.

Oxford, Art, Archaeology & Ancient World Library, STRACHAN.9

Another artists’ book includes an etching by Mario Avati of a creature that instantly calls to mind a mooncalf [2]: It has a cow’s head but many human arms and legs, and it seems to float in the sky above a village. It illustrates the short story ‘Un photographe à la campagne’ (‘A photographer’s day out’) by Lewis Carroll, in which a photographer attempts to take a picture of a cottage. During the long exposure time, a cow and a farmer next to the cottage move, and because of this they appear with many legs and multiple heads in the final photograph – fused into a grotesque hybrid in Avati’s illustration.

The German poet Christian Morgenstern (1871–1914) references mooncalves in his collection Galgenlieder (Gallows Songs), most explicitly in his poem ‘Das aesthetische Wiesel’ (‘The Aesthetic Weasel’) [3], shown in the display case alongside an English translation by Max Knight.

Ein Wiesel

sass auf einem Kiesel

inmitten Bachgeriesel

Wißt ihr

weshalb?

Das Mondkalb

verriet es mir

im Stillen:

Das raffinier-

te Tier

tat’s um des Reimes willen.

A weasel

perched on an easel

within a patch of teasel.

But why

and how?

The Moon Cow

whispered her reply

one time:

The sopheest-

icated beest

just did it for the rhyme.

It is not clear, what kind of creature this moon cow (in the original German version literally: calf) is. It could be a simple-minded human person or more of a mythical being – maybe a calf living on the moon?

In modern pop culture, the mooncalf’s transformation into a magical creature is fully carried out in the Harry Potter-universe in Johanne K. Rowling’s Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them [4]. They appear in the 2016 film of the same name as cute, long-necked animals with very large eyes on the top of their heads. These mooncalves are very shy and come out only during the full moon to perform complicated dances as part of their mating ritual. In this interpretation, no connection to the original meaning of the word remains.

- Christian Morgenstern, ‘‘Das aesthetische Wiesel’/‘The Aesthetic Weasel’’, in: ‘Galgenlieder. A Selection’, translated and with an introduction by Max Knight, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963).

- Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016), Image of ‘Mooncalf’ from film; © Warner Bros. Pictures

Display Case 3: Monsters of the Apocalypse

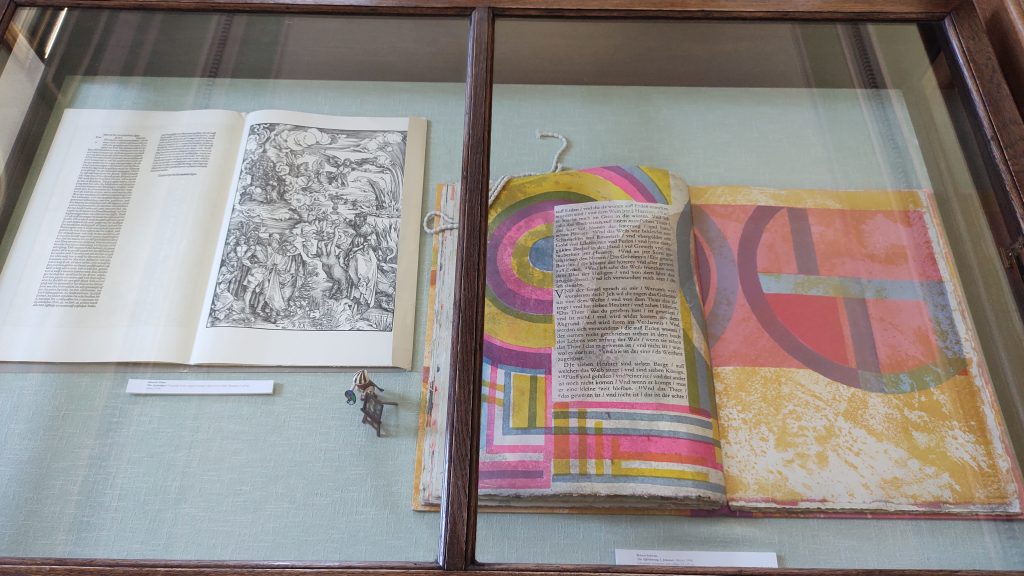

Monstrous births were often interpreted as signs of the coming end of the world and Judgement Day. And according to St John’s visions in the Book of Revelation, the end times were going to be populated with the most horrifying monsters yet. These vivid descriptions lent themselves to visualisation: The Revelation was throughout history one of the most frequently illustrated books of the Bible. On view in the display case is a facsimile of Albrecht Dürer’s (1471–1528) famous edition of the Apocalypse text illustrated by a series of 15 woodcuts, published in 1498 [1]. Shown here is the Whore of Babylon on the scarlet beast with seven heads and ten horns from chapter 17.

Next to Dürer’s Apocalypse is the modern 1994 Offenbarung S. Johannis by German artist Robert Schwarz (1951–) [2], opened to the same passage from Rev. 17. Schwarz used a facsimile of text from Luther’s Bible translation for his book, which he illuminated with radiant colours. The monsters in this version are recognisable only in the letters, the illustrations are completely abstract. But their vibrant colours and composition serve brilliantly to capture the visionary character of the text and its enigmatic nature. Schwarz produced only ten copies of his Apocalypse book, this one owned by the Taylor Institution Library is no. 7.

- Albrecht Dürer, ‘Die Apokalypse’; Facsimile of the original German edition from 1498 (München: Ludwig Grote, 1970).

- Robert Schwarz, ‘Die Offenbarung S. Johannis’ (Mainz, 1994); Lithograph, letterpress and collage; 55 x [?] cm.

Oxford, Taylor Institution Library, ARCH. FOL. G. 1994

Display Case 4: Monsters as harbingers of doomsday

The fourth display case shows more monsters of the end times.

The first object is a 15th century French miniature out of a series of illustrations to a popular medieval literary motive, the ‘Fifteen signs before doomsday’. The text consists of a list of 15 days preceding Judegement Day and describes various strange events and catastrophes that are prophesized to occur on each of them, culminating in the death of all living things, the end of the world and the Last Judgement. On the third day, all creatures of the sea (in this French manuscript: “monstres de mer”) come to the surface and cry to heaven, only God being able to understand them. The miniature [1] depicts two mermaids, pulling their hair in anguish, and various sea animals. The two large, rather scary looking “fishes” might be whales.

But even when Judgement Day has arrived, there are still monsters around, like in Hieronymus Bosch’s (c. 1450–1516) The Last Judgement Triptych [2]. Here they populate as demons the hellish landscape underneath the throne of Christ to torture the condemned sinners. They are portrayed as phantastic chimeras, put together from various animal and human parts.

- ‘The fifteen signs before doomsday (3rd sign)’, in: Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur (France, 1450–1470); Illuminated Manuscript; c. 24 × 17 cm (leaf).

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Douce. 134, fol. 42v - Hieronymus Bosch, The Last Judgement Triptych (after 1482); Oil on wood; 163.7 x 127.5 cm (middle panel), 167 x 60 cm (side panels). Vienna, Akademie der Bildenden Künste

The Reformation movement made use of the monstrous imagery of the Apocalypse to serve in their anti-papal propaganda. Andreas Osiander and Hans Sachs’ pamphlet “Eyn wunderliche Weyssagung” (“A Wonderous Prophecy”) [3] depicts the pope’s head on the body of the Dragon from Revelation 12 that drags a third of the stars from heaven with its tail and throws them to the earth. The accompanying text states: “It has an honourable face in the front, but at the back, with its tail, it bites secretly, treacherously and with cunning the sword of the word, so that its mouth bleeds, and still cannot break anything off it.” The sword is the sacred word of God that reveals the true, depraved nature of the pope-dragon.

Another Reformation pamphlet, the ‘Passional Christi und Antichristi‘ [4] by Johann Schwertfeger and Hans Cranach, juxtaposes the ascension of Jesus Christ with the fall of the pope into hell. The pope is described in the text as the false prophet or the Antichrist, who is cast into the depths of fire and sulfur in the Apocalypse, surrounded by demons of all shapes and sizes.

- Andreas Osiander and Hans Sachs, Eyn wunderliche Weyssagung / von dem Babstumb / wie es yhm biß an das endt der welt gehen sol / in figuren oder gemaͤl begriffen / gefunden zu Nuͤrmberg / ym Cartheuser Closter / vnd ist seher alt. (Nuremberg: Hans Guldenmund, 1527).

Oxford, Taylor Institution Library Arch. 8° G.1527(8) - [Johann Schwertfeger and Hans Cranach], Passional Christi und Antichristi ([Erfurt]: [Matthäus Maler], [1521]). Oxford, Taylor Institution Library Arch. 8° G.1521(19)

- Jean Baptiste Trento, Pierre Eskrich et al., ‘MAPPE-MONDE NOUVELLE PAPISTIQUE’ (Geneve, 1566). Reproduction of original: (Woodcut and letterpress; 28 sheets; each 43.18 x 34.29 cm.

Ashmolean Museum Oxford, Acc. no. WA 1863.13657.1-28

The ‘Mappe-Monde Nouvelle Papistique‘ [5], printed in Geneva in 1566/67, is a very special medium of anti-papal polemics. On the giant map, the popish world is inside a monstrous hellmouth, attacked by protestants from all directions. This well preserved copy was only recently discovered in the Ashmolean museum’s Douce collection – the 28 unmounted sheets had been kept in an inadequately labeled box. Due to this, the Ashmolean copy has not yet been included in any scholarship about the Mappe-Monde Nouvelle Papistique.

The Reformation movement were not the only ones who used monsters for their propaganda. Their opponents on the Catholic side interpreted the same monstrous births to be warnings against the heretics of Luther. These texts, which were often written in Latin in the beginning, were not always able to reach as big an audience as the vernacular ones of the Reformation. But there were also those which very effectively utilised the monstrous for their means. The humanist and controversialist Johann Cochlaeus (1479–1552) made Luther himself into a monster by giving him seven heads and claiming Luther split “from himself into seven heads of which every one wants to be right”. The title page of his work ‘Sieben Kopffe Martini Luthers Vom Hochwirdigen Sacrament Des Altars’ (‘The seven heads of Martin Luther. A Treatise on the Holy Sacrament’) [7] depicts the surrealistic metaphor in a woodcut illustration. A few decades later, the Franciscan and Counter-Reformist Johannes Nas (1534–1590) conceived a whole apocalyptic, militaristic procession of protestant monstrosities against the holy church in his Ecclesia Militans [6]. It even includes the Monk Calf!

- Johannes Nas et al., ‘Schaw Leser diese Bildern an, Und dich darbey selbsten gemahn, Wasz massn Ecclesia militans, Heu clamet parturiens’ (Ingolstadt, 1588). Woodcut and letterpress; 61.5 x 36.4 cm (sheet size). London, British Museum, Reg. no. 1880,0710.340

- Johannes Cochlaeus, ‘Sieben Kopffe Martini Luthers Vom Hochwirdigen Sacrament Des Altars’ (1528). Oxford, Weston Library, Tr. Luth. 102 (12)

The seven heads of Martin Luther. A Treatise on the Holy Sacrament by Johannes Cochläus

- Doctor

- Martinus

- Luther

- Ecclesiast

- Schwirmer

- Visitator

- Barrabas

Display Case 5: Apotropaic monsters – Gargoyles, Emblems and Magic

Drawings of the fantastic beasts on the Norman capitals in the Crypt under St-Peter-in-the-East, one of the plates made by Michael Burghers for Thomas Hearne’s edition of John Leland’s “Collectanea” (1715)

While many historical monsters were purposed to signify the presence of evil, to act as foreboding indicators of doom, some depictions of monsters are used for the purpose of good. Whilst walking around Oxford, the oldest monsters can be spotted on the two Norman parish churches of St-Mary-the-virgin in Iffley and St-Peter-in-the-East, now library to St Edmund Hall.

Single beakhead found under the floor of St-Peter-in-the-East during the conversion into a library. With thanks to the librarian James Howarth for arranging the loan to the exhibition.

Additionally, you may notice many ghoulish adornments to the surrounding buildings, or animal-like grotesque figures carved into pillars. These, as you may know, are Gargoyles. The origin of this term may not be what you initially think, as it etymologically descends from ‘gargouille’, a French term related to the act of swallowing. This is because Gargoyles are often purposed as rain funnels, protecting the rest of the building from rain-based erosion. However, many believe in Gargoyles as apotropaic, meaning they ward off evil from the locations they adorn. This is founded in history stretching back to the medieval period, with churches carving grotesque figures into their walls to deflect evil. In Oxford, like the replica in this cabinet, many grotesques and gargoyle-like monster figures can be found in dark corners of cloisters or archways, providing some artistry and talisman-like properties to these otherwise lifeless areas.

- Elena Trowsdale, Facsimile of a gargoyle from Merton College Oxford (2023); White modelling clay; approx. 10x10cm.

- Chris Andrews, Oxford Gargoyles: A Little Souvenir, (Oxford: Chris Andrews Publications, 2006). Purchased from Weston Library Gift Shop

Across different cultures, different apotropaic devices are used to ward off evil, such as the evil eye in Greece, and can often be sold as tourist souvenirs. The question of the superficiality of these monstrous tokens compared to gargoyles is up for debate – does commercialism rid emblems of their significance? Would you think of a gargoyle bought from the Weston gift shop in the same way as a gargoyle carved into a college for 400 years? Which seems more scary?

- Evil Eye

Some grotesque or monstrous emblems function less to ward off evil, and more as reminders of the evil persisting in certain locations, de-sensitising the viewer to the shock of immoral occurrences. For example, the necklace in the display below is a tourist souvenir of a historic emblem significant to the island of Lanzarote. In the 18th century, a cataclysmic volcanic eruption struck the island, leaving its landscape permanently effected even today. The devil depicted is the emblem of the national park of Lanzarote, Timanfaya, and is said to have derived from a folk tale about a husband who lost his wife to the lava flow, meaning he ran around the island manically with a five-pronged fork, being called ‘poor devil’ by onlookers. Today, the devil is a friendly symbol, associated with the heritage of the island and sold in many gift shops. He symbolises past evil and hardships, but also the persisting spirit of the island’s locals, these two symbols happily merging to combine the Island’s past with its present.

- César Manrique, Souvenir necklace depicting ‘The Devil of Timanfaya’; Metal and string; purchased from Lanzarote, from the private collection of Elena Trowsdale.

2 thoughts on “Early Modern Monsters in the Taylorian”