This article was originally posted on the Taylor Reformation blog which has now become part of the Taylor Editions website with a dedicated Reformation Pamphlets series.

Reformation Recipes at Oriel College, Oxford, November 6th 2017

hosted by Marjory Szurko

I have been hosting Edible Exhibitions at Oriel College over many years – translating and transcribing the recipes for sweet dishes from various centuries and baking them with the help of colleagues. To celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, I decided to try Reformation Recipes – recipes from 14th-16th centuries, on Monday November 6th, 2017. One of the books which helped me most was Volker Bach’s The kitchen, food, and cooking in Reformation Germany, published in Maryland by Rowman & Littlefield in 2016. It contained recipes translated from the German, and a myriad of interesting facts and background details about life during the Reformation period.

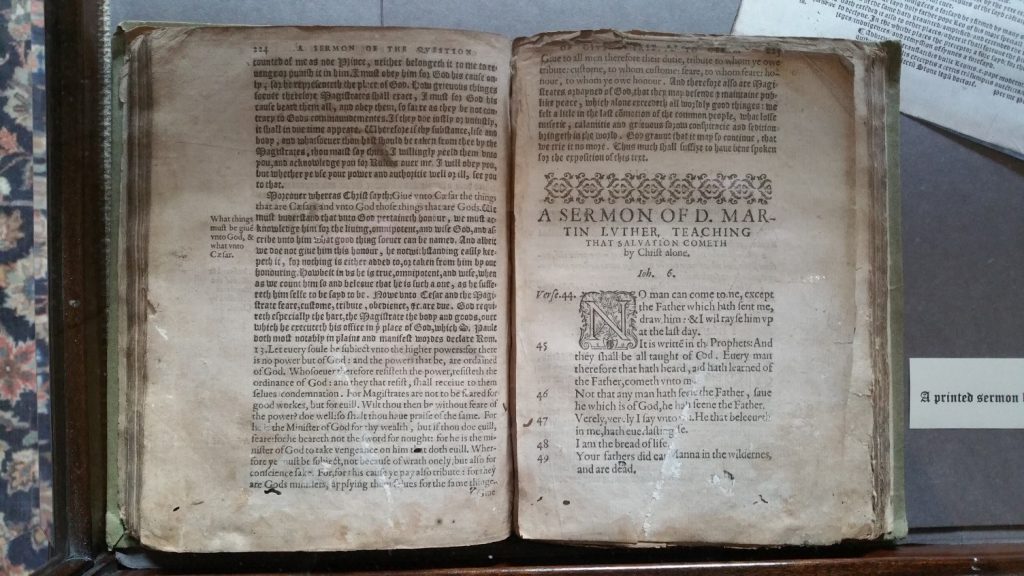

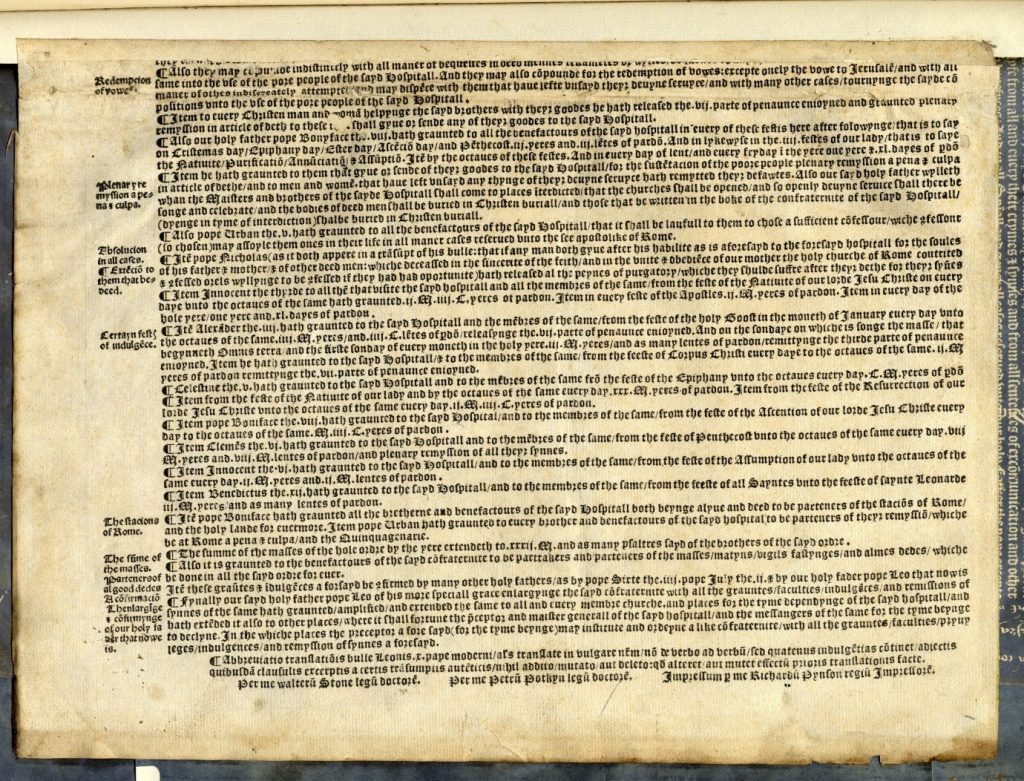

Items relating to the Reformation from Oriel’s Library Collections

Printed by Richard Pynson in 1516. Oriel College D.B.ii.10

You might think that the food of earlier centuries was boring and tasteless – not a bit of it! Many people had returned with spices from the Crusades or pilgrimages to the east, and had the knowledge of how to cook with them; and they incorporated these flavours into the dishes that they prepared in Britain and Europe. Ginger, cinnamon, pepper and saffron were very widely used, and honey often took the place of sugar, as cane sugar, imported from the east, was prohibitively expensive. Even so, most recipes were written down by chefs working for the nobility or the Royal court, or occasionally written by noblewomen for their households.

Unsurprisingly, bread was the mainstay of the 16th century diet. The people of all religious persuasions prayed: ‘Give us this day our daily bread’ – bread stood metaphorically for all food, and bread and salt had forever been the symbol of hospitality in the home. Hieronymous Bock, in his work Die Teutsche Speiβkammer (The German larder), says ‘…no food, without bread, however delicious it may be, can nourish men in bad times and keep them alive…’ xli, v.

Bread did not have to be ordinary, though – recipes for gingerbread start in the 15th century if not before, and old bread is used up by these means – breadcrumbs are the method used to stiffen the dough of many a recipe from the fourteenth century onwards.

Some 15th and 16th Century recipes

Here is a very popular recipe that was used in the Edible Exhibition. It comes from MS Harley 279, which is housed in the British Library, and is taken from Two Fifteenth-Century Cookery-Books… ed. Thomas Austin, Oxford, published for the Early English Text Society (Original Series 91) by Oxford University Press in 1888, reprinted 1964, p.35:

15th Century: Gingerbread

Gyngerbrede. Take a quart of hony, & seethe it, and skeme it clene; take Safroun, pouder Pepir, & throw ther-on;take gratyd Brede, & make it so chargeaunt that it wol be y-leched; ; then take pouder Canelle, & straw there-on y-now; then make yt square, lyke as thou wolt leche yt; take when thou lechyst hyt, an caste Box leves a-bouyn, y-stykyd ther-on, on clowys. And if thou wolt haue it Red, coloure it with Saunderys y-now.

(Harl. 279 p.35 iiij)

2 cups clear honey

Pinch of powdered saffron

½ teaspoon ground black pepper

1 teaspoon of cinnamon

2 loaves (18 cups) fine white breadcrumbs or as needed

Cinnamon to coat as desired

Bring the honey to the boil, reduce heat and allow to simmer for 5 or 10 minutes, skimming off any scum that forms on the surface. Take the pan off the heat and add saffron, pepper, cinnamon and bread crumbs (adding bread crumbs a cup at a time. Mix well and scoop out into half inch sized portions. Form into small balls and coat with cinnamon. Decorate with cloves and box leaves if desired.

There were many different recipes for gingerbread. Here is another, made with marzipan. Marzipan, or ‘marchpane’ was thought to have come to Europe from Persia (modern Iran) through the Turks, and was found as early as the 12th century in Sicily.

16th Century: White Gingerbread

(This recipe comes from Brears, Peter All the King’s Cooks. London: Souvenir Press, 1999)

225g (8 oz) marchpane (almond paste) 15 ml (1 Tbsp) ground ginger

225g (8 oz) sugar plate (fondant icing)

Knead the ginger into the marchpane and roll it out on a board dusted with icing sugar to about 7 mm (1/4 inch) in thickness.

Divide the sugar plate into two, and roll out one piece into the same size as the marchpane. Dampen one side of the marchpane, and place it damp side down on the sugar plate. Next, roll out the other piece of sugar plate, dampen the other side of the marchpane, place the sugar plate on top, and smooth it down. Then roll the marchpane and sugar plate (white gingerbread) sandwich to around 7 mm (1/4”) in thickness.

Cut the gingerbread into small diamonds or rounds, or press the sections into moulds, trimming off the surplus with a knife, and leave to dry. Any unused trimmings may be kneaded together and cut into shapes as well.

One of the ingredients used often in baking in the early centuries was soft curd cheese. Combining this with a few drops of rosewater gives it a deep, rich flavour.

16th Century: Curde Tarte

(recipe from The Good Huswifes Handmaide for the Kitchen, Lond: R. Iones, 1594.)

Take Creame, yolks of Egs, white bread, seeth them together, then put in a sawcer full of Rosewater or Malmesey, and turn it: and put it into a cloath, when all the whey is out, straine it, and put in Synamon, Ginger, salt and Sugar, then lay it in paste.

Filling:

Large tub plain cottage cheese (6 oz)

3 eggs, beaten

Few drops rosewater

¼ teaspoon each cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, salt

2 oz caster sugar

2 oz breadcrumbs

½ pint double cream

¾ lb butter, melted

Beat together all the ingredients, adding the melted butter last. Line a baking dish with pastry and pour in mixture. Bake in oven at 400ºF (Gas6) for approximately 30 minutes until slightly risen and golden brown.

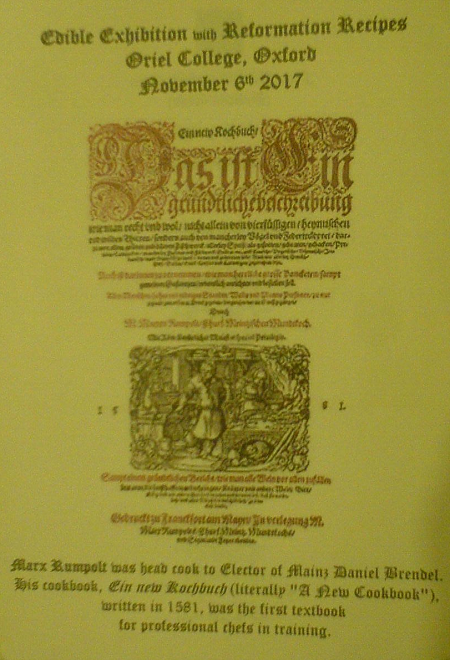

Marx Rumpolt was head cook to Daniel Brendel, Elector of Mainz. His cookbook, Ein new Kochbuch (literally ‘A new Cookbook’), written in 1581, was the first textbook for professional chefs in training. One of his recipes was for an early type of meringue – he called them ‘Rusks of pure sugar’ – which indeed, they are!

Rusks of pure sugar (Meringues)

(Recipe 170 (CLXX) translated from Ein New Kochbuch by Marx Rumpolt and taken from Volker Bach’s The kitchen, food and cooking in Reformation Germany. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016)

Take sugar that is ground finely and white and the white of a fresh egg. Pound that in a mortar with a drop or four of rosewater…when you have stirred it…drop the dough on clean paper, with a wooden spoon, about the length of one finger. Put it into a cool oven quickly so that it does not flow off the paper, and it will rise nicely. When it is cold, it becomes so crumbly that it melts in your mouth. This is called rusks of pure sugar. If you want them brown, you can mix ground cinnamon among them. If you want to make them very brown, soak them in the whites of eggs, especially that which you pound with much good white sugar.

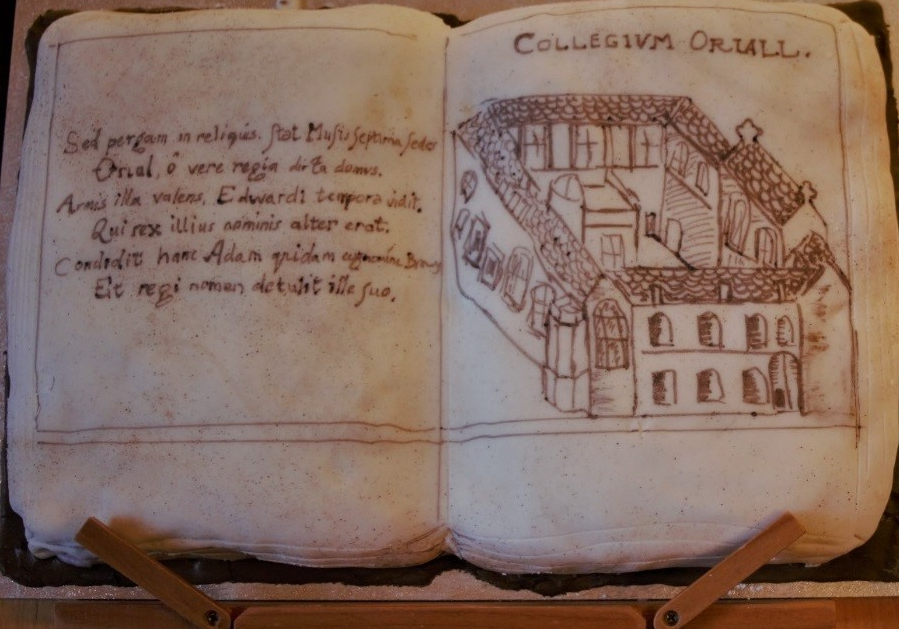

Meals in the early centuries often ended with a Subtlety or Soteltie – a confection in sugar or marzipan. The subtlety made for the Edible Exhibition reproduced below represents the Oriel buildings in the 16th Century as drawn by Bereblock. The drawings complement Thomas Neale’s inventive text in a book made to present to Elizabeth I on her visit to Oxford in 1566. This manuscript is in the Bodleian Library, and the cake was modelled on the copy of the manuscript in Queen Elizabeth’s Book of Oxford, edited and with an introduction by Louise Durning, Bodleian Library, 2006.

Photo: David Archer