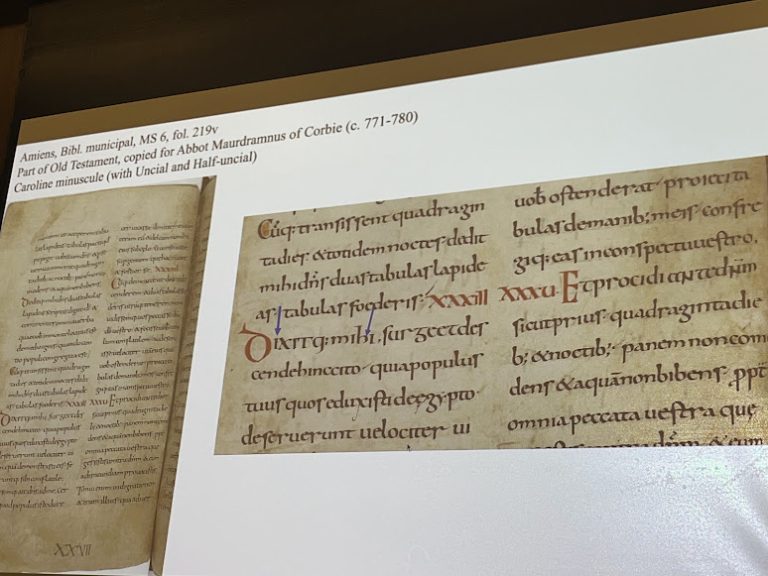

Of making many books there may be no end, but studying the boundless treasure of manuscripts held in the Weston Library is anything but a weariness of the flesh. That was, at least, the experience of the MML History of the Book students on Wednesday of 2nd week as they ventured up to the Horton Room for a lively session that combined a whistle-stop tour of medieval palaeography with chances to examine, quite literally in the flesh, the scripts, writing materials and bindings whose histories we had only just studied.

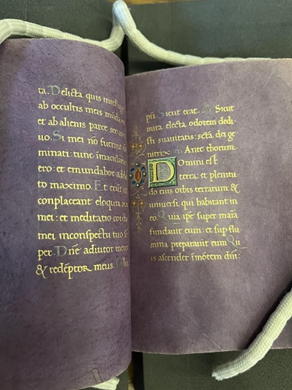

Dr Laure Miolo, already well-known to many in the group who have been attending her Palaeography sessions in Old French and Latin with much enjoyment, began by discussing Palaeography as a discipline and its seventeenth-century French origins, before moving on to outlining a general typology of scripts (with the usual warnings against over-simplification this entails). A consideration of different writing surfaces brought us to purple manuscripts, and what fun it was to be able to examine Bodleian MS. Canon Liturg. 287, a fifteenth-century Italian Book of Hours. It is exceptional not just in its material beauty but also, as Prof. Henrike Lähnemann pointed out, that it cannot be used as a Book of Hours at all, being in fact just a hodgepodge of cuts left over from finished books. For whomever bought this book, its status as an object was far more important than what was to be read inside.

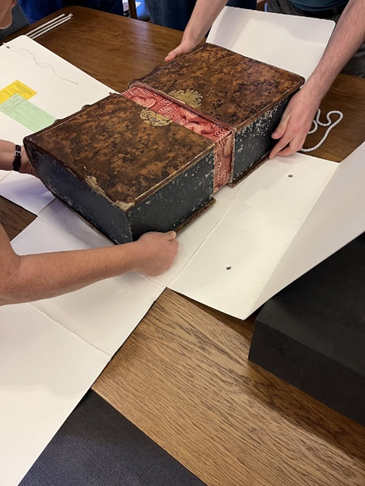

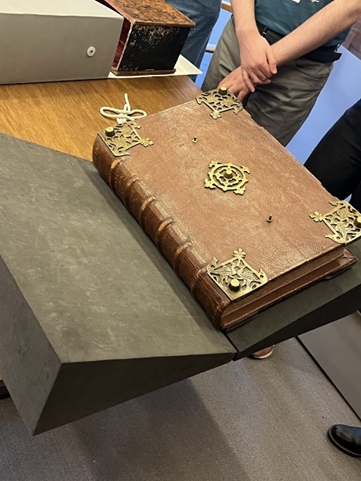

We must also thank Dr Alison Ray for choosing and showing us so amazing an array of manuscripts. This meant that discussions of chaining books and why libraries needed to chain certain books and not others were accompanied by examination of a chained manuscript from Nuremberg, whilst the Weston special collections’ unending variety was exemplified by the biggest and smallest books we saw: the Oxforder Bibelhandschriften MSS. Bodl. 969 and 970, the latter so great that Prof. Lähnemann and Dr Dunning struggled to remove its from its case (and the former was not attempted!). The smallest, MS Ashmole 6, a handily-sized compendium of astronomical tables with a fold-out calendar, is bound very curiously indeed.

My own favourite was perhaps MS Douce 118, the ‘Aspremont Psalter’, made in Lorraine at the turn of the fourteenth century. Appreciating just how many different elements come together in the making of a manuscript – ink, binding, writing surface, the organisation of quires and even pagination – doubtless leads to a more full understanding, both of how these books were used in the past and the texts within them. That Psalters like this were still not paginated in the 14th century points to just how well its readers knew their way around it. And through this understanding we come a little closer to those whose objects these were: whether they owned them only for show, or whether indeed they were their close companions, meditated on die ac nocte.

But it’s just as fun to find the things you would never have expected: