by Charlie Burrows (MSt. Modern Languages)

Over the holidays, this year’s History of the Book class was set the simple but daunting task of choosing a book to present to the class during their first session of Michaelmas Term. Students might have been lured into thinking this to be an easy task when compared to their usual far more time-consuming challenge of the essay: all they had to do was pick a book from their bookshelves. Yet, as students started to reflect on their choice, they might have felt a degree of pressure, even apprehension (I know I certainly did!), in the task of presenting a book to potentially a room full of strangers, with a new professor, in a new university. For in choosing a book, we inadvertently tell others a little about ourselves: we might give away what languages we speak, what periods and topics fascinate us, perhaps something about our own family history, even our religion. Or quite simply our own tastes: what moves us, what makes us laugh, and what we find beautiful. Our choice in book, might also express not only what we read, but how we read it: are our books blemished with the brown marks of coffee stains, our front covers faintly scarred because coffee cups have rested hours on them when no coaster is at hand (as indeed was the case with one member of the classes book!), our pages brimming with annotations, our page corners folded over as book marks. Or do our books show little traces of having been lived in because we tend to them as if they are our utmost treasures.

In a world where books are everywhere, where a new book is published every half a minute, the underlying instinct of the class seemed to be to start seeing books as more than mere everyday objects, more than convenient makeshift coasters for our mugs!

So without further ado, here is what everyone brought along:

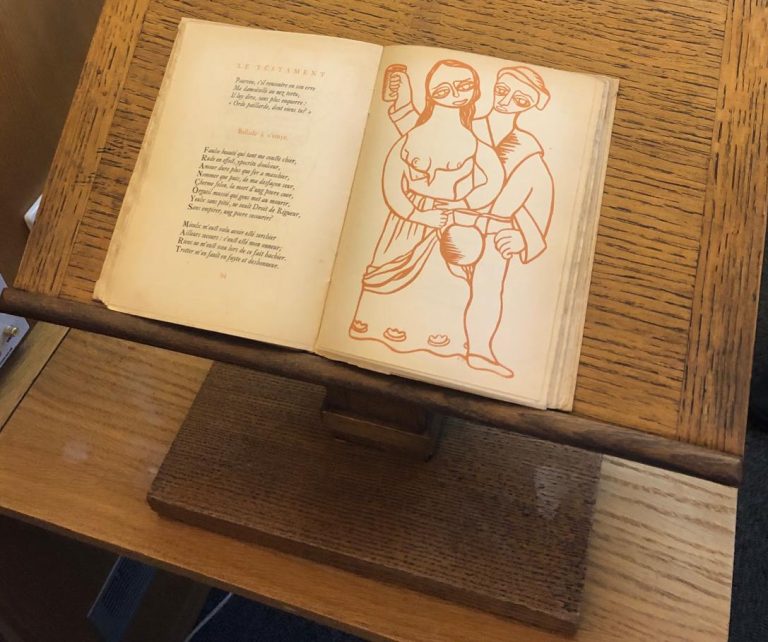

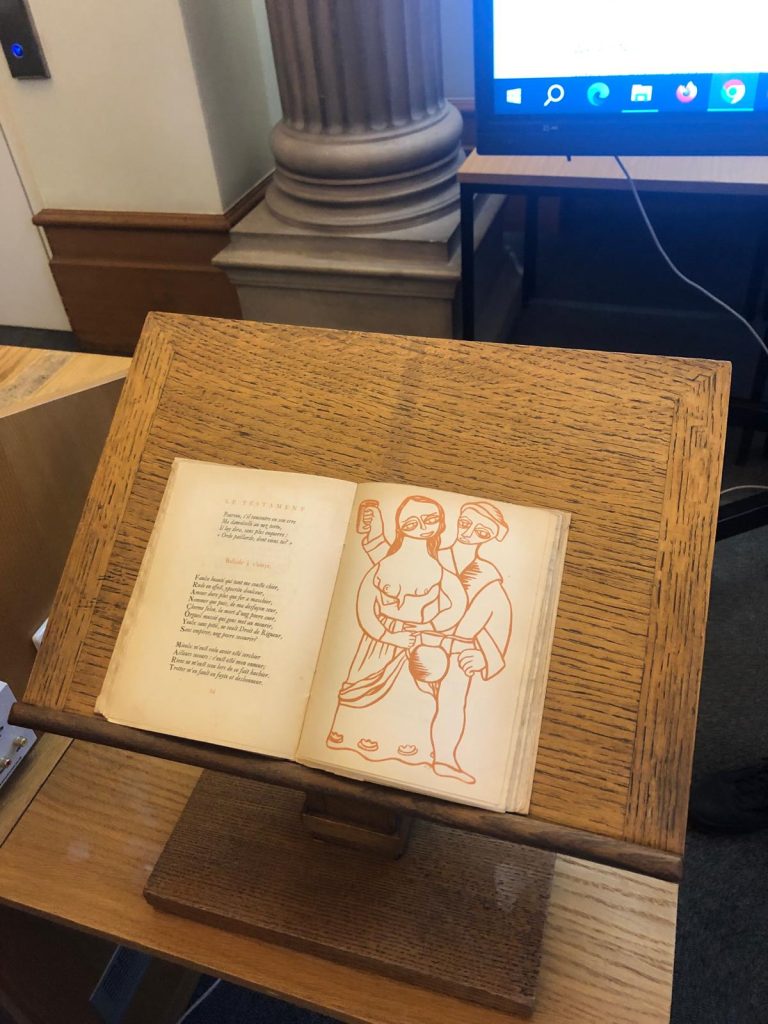

Lucian Shepherd – This edition of François Villon’s Lais and Testament represents a confluence of the late Middle Ages and 20th century Paris. Printed in 1947 by J. Dumoulin under H[enri] Barthélemy, it belongs to a commercial series for public consumption entitled ‘Le Ballet des Muses’. Scattered throughout are surrealist and eroticised illustrations by Françoise-Émilie Dangon, whose works beyond these remain sadly unknown to me. What marks this book out as a 20th century Parisian product, is its limp binding which would typically be later rebound; its rough paper pages torn at the top when first cut open; and how I acquired it: bought from a bouquiniste stall along the bank of the River Seine. This example of medievalism stands further in the context of the poètes maudits where Villon is seen as a fore-figure to 19th century poets such as Baudelaire and Rimbaud. For this reason, Villon’s texts attracted a growing readership from those in search of texts just as daring, rebellious and unconventional as Les Fleurs du Mal and Illuminations. Though this object is merely copy number 1758 of 3,750, it tells a unique story, bridging centuries.

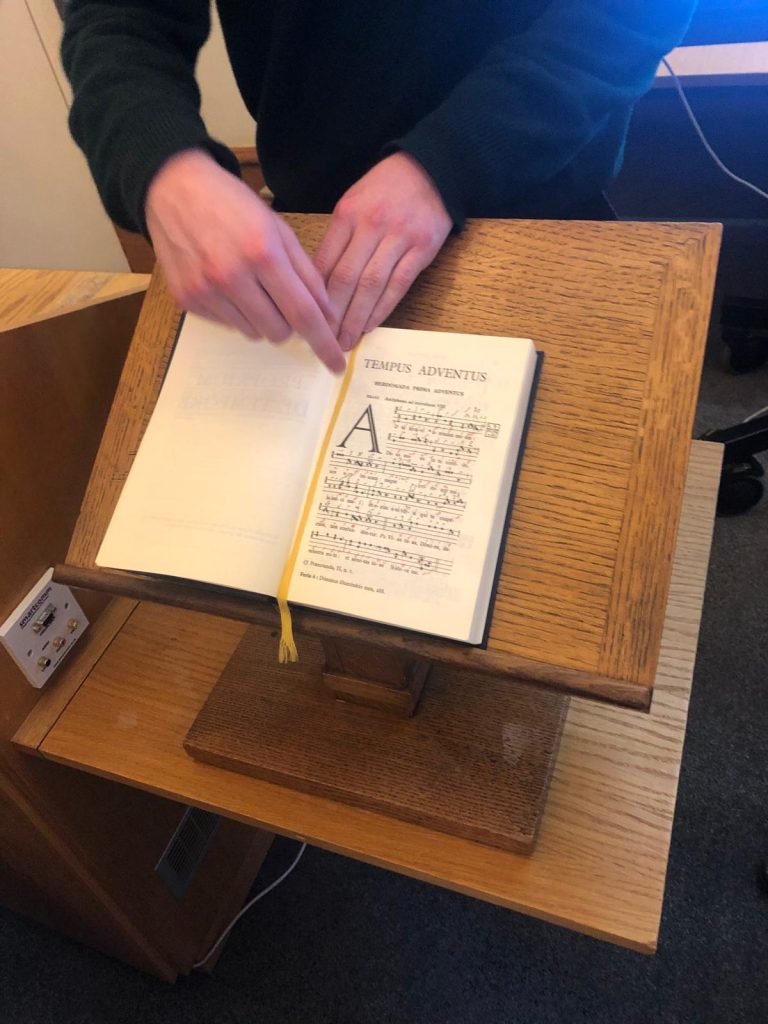

Monty – The Graduale Triplex was published at the Abbey of Solesmes in 1973. As is standard for a hymn or prayerbook, which may expect to see decades of regular use, it is hardback and bound with an imitation-leather finish. The quality of the paper used in the pages is low, however. The book imitates to some extent the medieval manuscripts, from St. Gallen and Laon, on which part of it is based. Two scribes transcribed by hand the ‘neumes’ from these manuscripts on top of the new Graduale Romanum, published one year previously, which contains the Gregorian chants sung during Mass, but written only in (modern) square notation. The neumes, which might seem like little squiggles, allow a much more nuanced and varied interpretation of the chant than square notation alone, which explains its importance: just as the book functions as a collection of handwritten copies of parts of medieval manuscripts, so the singer consulting it can sing in a manner far more faithful to the original piece.

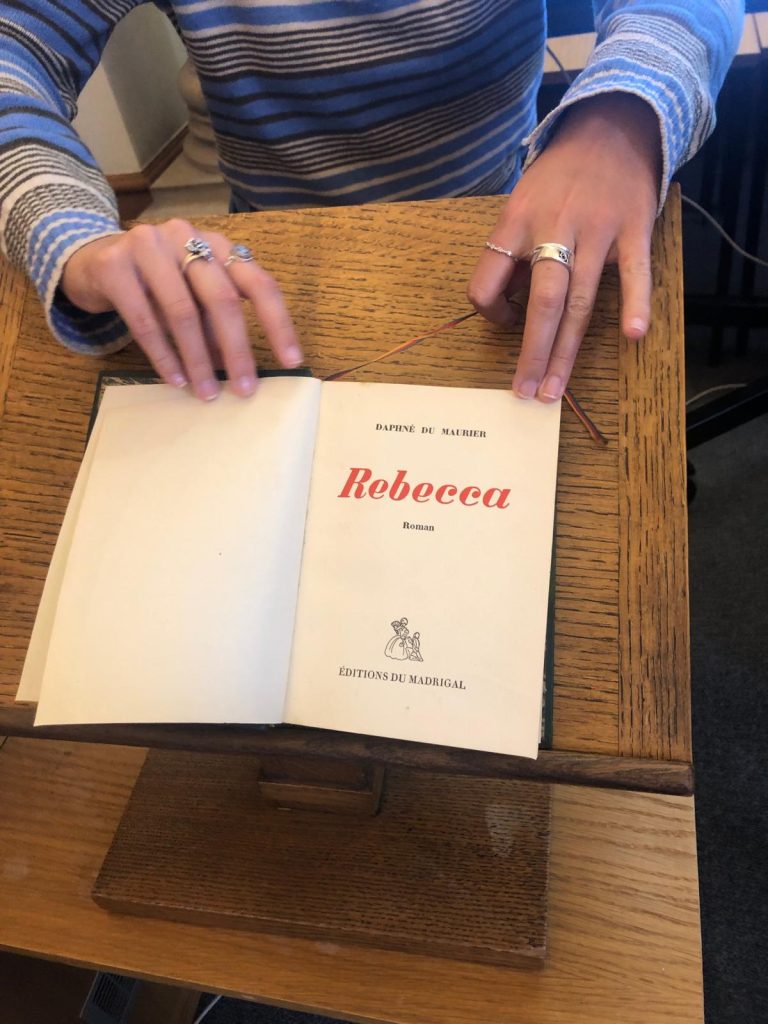

Edie – I brought in a French translation of Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier published by Éditions du Madrigal in 1949. The book had been rebound (with the original cover looking suspiciously like a Gallimard edition!) in leather with raised bands along the spine, which we determined were decorative rather than functional. I also chose this book because of the name, H. Weyland, written in the front. I really enjoyed the idea that another Anglophone reader had owned the same copy of an originally English text translated into French that I now owned!

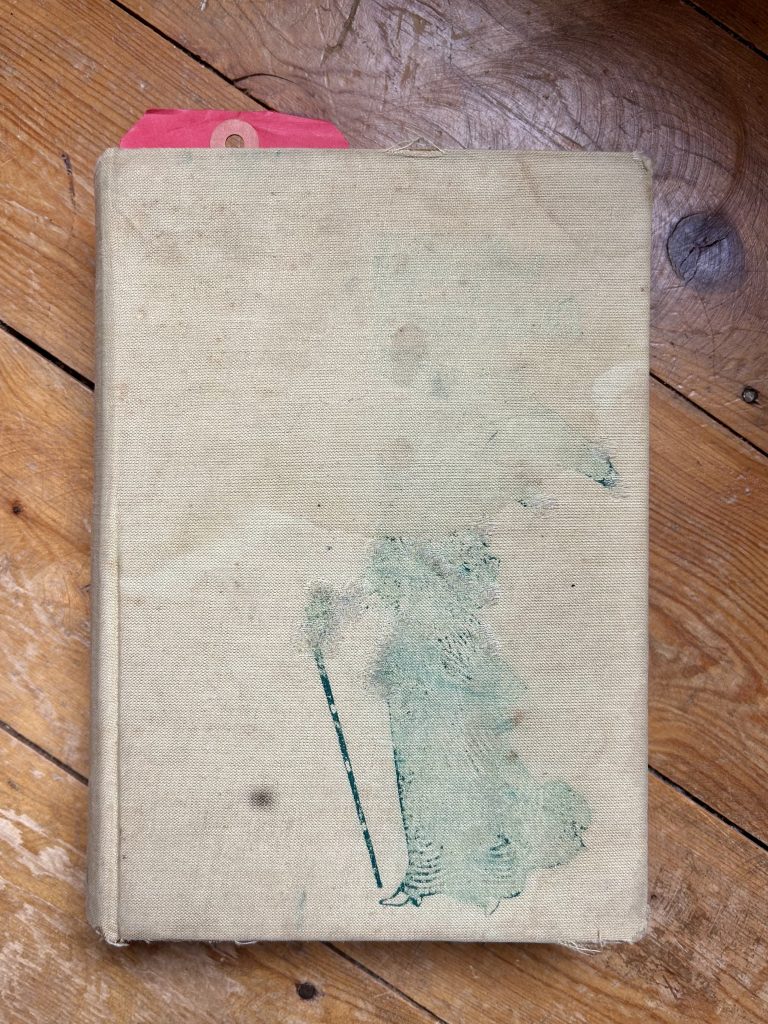

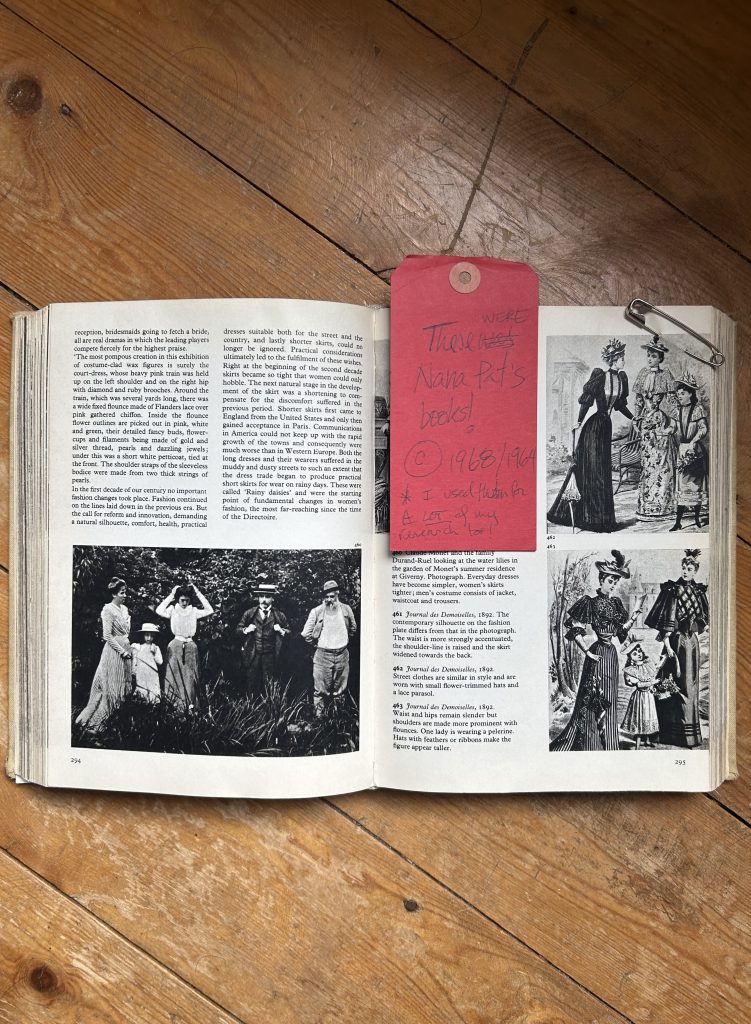

Molly – The Pictorial Encyclopedia of Fashion by Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová, and translated by Claudia Rosoux is not a striking book; its chipboard cover stretches a sun-bleached and water-stained cloth binding around the pages, its headbands similarly plain. The title has nearly faded from sight, and only the hemline of a woman’s billowing skirt remains from what was (presumably) her entire person. Opening the book is quite a different experience. Within its pages are 5,000 years of fashion history—up until 1967, that is, the year before the book’s publication—taking the form of a visual encyclopedia and glossary. Images abound, almost to a dizzying extent. But my reason for selecting this particular book as a means of introduction to our class is neither its formal features as a book-object nor even its content per se. Rather, its significance lies in the personal history that it preserves. This encyclopedia was first owned by my grandmother, a fashion designer, and later given to my mother, a costume designer, before being passed to me for use in my own research. Published in New York in 1968, my grandmother purchased it in Manchester within the first year of its release and then brought it with her to Canada in 1969. What fascinates me is the material evidence of its use over the years: my grandmother’s name inscribed inside the cover, a note my mother left tucked between the pages when she handed it down to me (on a form of paper tag that seems nearly infinite in her design studio), and a safety pin piercing the top corner of a page, masquerading as a bookmark. The accoutrements of their industry have become embedded into the text that tells its history. It’s not just a book—it’s a dynamic artefact, bearing the marks of its owners.

Charlie – There was a time before books and paper, even before manuscripts and parchment, and in this time the material of writing was papyrus! Inspired by Dr Peter Tóth recent talk on books in the ancient world, at the Weston library’s wonderful weekly coffee morning (please come along, every Friday at 10:30 in the Weston!), I chose to present Irene Vallejo’s beautifully written Papyrus The invention of Books in the Ancient World, as a sort of pre-history to the History of the Book course. Through many entertaining anecdotes, Vallejo leaves us with the lasting impression that in the antique world books were something cool and sexy! She gives us the fragment of the beginning of a play where a merchant is trying to entice a girl to move to Alexandria with him. He lists the wonders of the city: the warm climate, the abundance of wine, the beautiful youths in the gymnasiums, and books. Yes, books were a reason to pack up and move to a city! Or there is the anecdote of how Mark Anthony wooed Cleopatra, not with the usual riches or jewels, but with books: 2000 for the great library at Alexandria. Whilst, apparently Alexander the Great was in such adoration of The Iliad that he would sleep with it under his pillow. More poignantly, she recounts how archaeologists found a papyrus scroll next to a female mummy, the implication being that this lover of books wanted to take her most beloved book with her, beyond the river of forgetfulness, into the next life. Our History of The Book story, may start, in the Medieval period, from where Vallejo’s story stops, but I think what is worth taking over is the reflection that books have not always been common place items, they have also been objects worthy of dazzling queens, seducing love interests, and to being buried next to for eternity.

Sveva – The book I chose for our introductory lesson is Cleopatra and Frankenstein by Coco Mellors, a modern novel that tells the story of Cleo, a young British artist, and Frank, a middle-aged advertising executive, whose impulsive marriage in New York City brings to light themes of love, identity, and mental health. Their relationship reflects the complexity of modern relationships, where age gaps, emotional struggles, and self-discovery collide. I chose this particular book to introduce myself as it aligns with my focus on contemporary literature, especially works that delve deeply into human connections and personal relationships. Published by 4th Estate (HarperCollins) in 2022, the novel has a short history, and no particular facts related to its printing or marginal notes, however, it has been praised for its raw portrayal of modern life. Its themes of identity, creativity, and emotional vulnerability resonate with my literary interests, making it a fitting introduction to my focus on people-centered narratives.

Viviane – Thüring von Ringoltingen’s Melusine was written in Bern in 1456 and is one of the first German prose novels. Following the medieval understanding of literature the novel is not an independent piece of literature but a reworking of a source. The medieval prose novel takes the place of the former traditional epic verse poetry and corresponds with the beginning of the printing press. The main plot of the Melusine theme is the relation between a non-worldly being and a human. The non-worldly being usually leaves the worldly order and a worldly partner after a special event, usually the passing of a prior formulated rule. The presented version of the book is a Reclam edition from 2020 which contains pictures of the original woodcarvings. Because of its small size the book is very handy and can be transported conveniently. The book was chosen for the presentation because of its practical format, and my interest in the Melusine-theme and early prose novels.

Nina – I brought the Mittelhochdeutsches Taschenwörterbuch which is the principal dictionary of the Middle High German language by Matthias von Lexer, a German lexicographer and medievalist. Originally published in 1879, my edition contains a postscript by medievalist Ulrich Pretzel and was firstly published in 1992. I bought it when I started studying back in 2019, convinced I would only need it for the first year at university in which medieval studies are a mandatory subject. Unexpectedly, I got more and more fascinated by the diversity of medieval literature and language and enrolled for many medieval seminars during my undergraduate degree, even ending up writing my bachelor’s thesis on a medieval text. During this time, this book became a faithful and indispensable companion, helping me to understand and translate Middle High German texts and to further develop my interest for medieval studies – which is the reason why I brought it to Oxford.

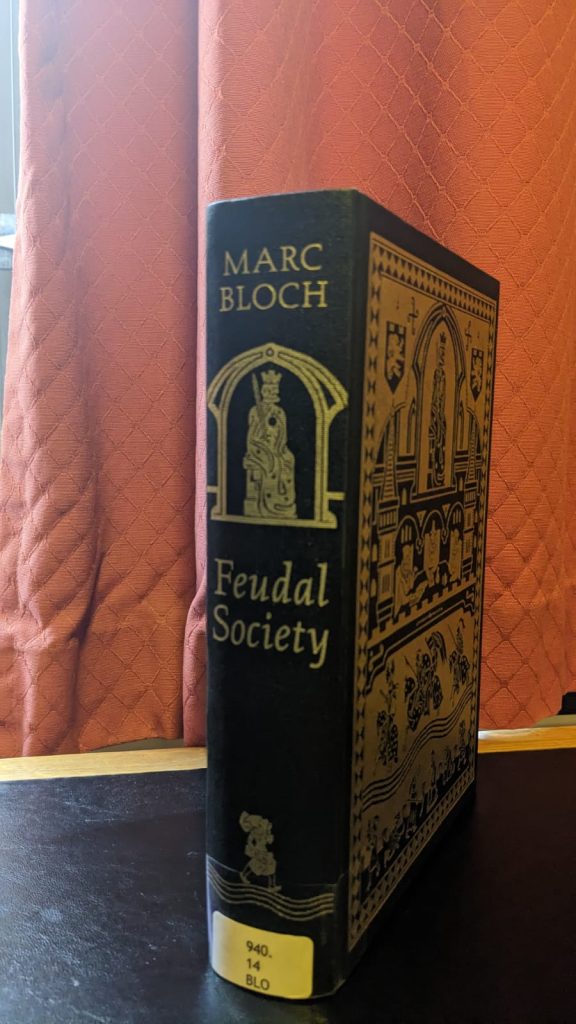

Mathew – I brought a folio edition of Bloch’s Feudal Society. The decoration on the volume, including the gold woodcut-style print on the cover, shows an impulse towards medievalism. I found the volume interesting for reasons relating to both the story of its author and the materiality of the book I own. First published in 1939, Feudal Society appeared just a few years before Bloch’s execution at the hands of the Gestapo for his role in the French Resistance. The book I own was bought online, and has in it an ex libris marking its donation to Latymer Upper School in London. The library slip inside, however, shows that it was never taken out, and in fact it appears to have been removed from the library just a few months after it was donated – evidently not all donations are appreciated equally!

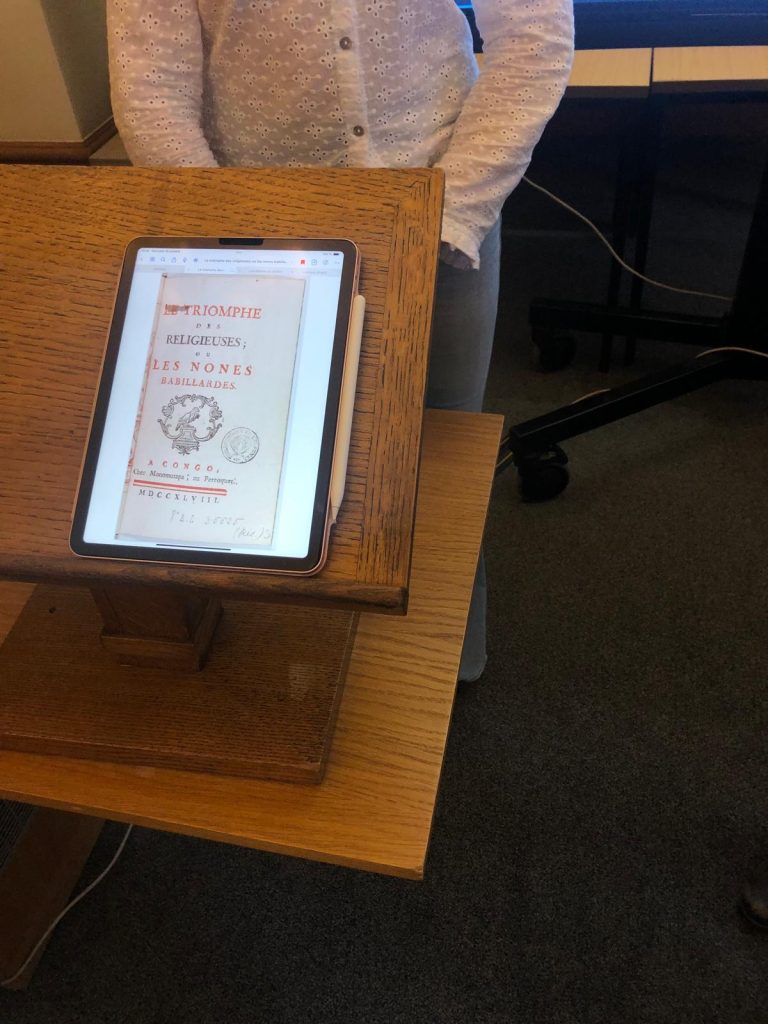

Erin – For my book, I chose Le triomphe des religieuses ou les nones babillardes, published in 1758. I chose this book for two reasons: firstly, the binding and decorative elements are typical of eighteenth century French books; and secondly, because it has a peculiar history. Unfortunately, as the book resides in the archives of the BnF in Paris, I could only bring a scanned version on my iPad. Formerly belonging to a lawyer who later sold his library to the BnF, this copy has a beautifully intricate ex-libris stamped into the book, giving us a glimpse into its ownership history. The most interesting element of this book is its genre: as a libertine convent novel, it would have been forbidden to publish, sell, or possess any copies of the book in eighteenth-century France. Writers and booksellers would have been faced with a hefty punishment if found to have dealt such scandalous material! Therefore, the book has no known author, and according to its title page, it was published in Congo (unlikely!).