by Imogen Lewis (MSt. Modern Languages)

Palaeography. Now halfway through Michaelmas term, History of the Book students may just about be able to spell the term – but do we really know what it means? Having stroked many a book, discovered the secrets contained within their binding, and even learned to painstakingly typeset our own, we now take a step back and study something we may have taken for granted thus far: The script contained within. More specifically, how script and the surfaces upon which it is written evolved, and how its study is paramount when working to date manuscripts.

During Week Four’s session in the Weston Library we met with dream team Dr Laure Miolo and Dr Alison Ray to talk all things palaeographical, from the term’s coining in 1681 in Jean Mabillon’s ‘de re diplomatica‘, all the way to the hallowed studies of Bernhard Bischoff three centuries later in 1990. Special thanks must also go to Dr Andrew Dunning, R.W. Hunt Curator of Medieval Manuscripts at the Bodleian, for giving us access to some invaluable materials for this session.

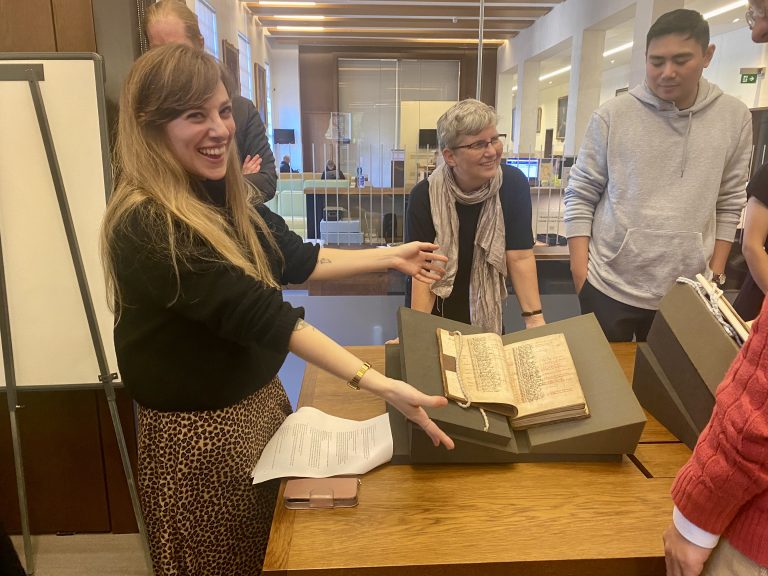

The session itself worked as a sort of back and forth between learning about the theoretical aspects of Palaeography through a series of insightful presentations given by Dr Miolo, to then applying this theory in the study of physical manuscripts introduced by Dr Ray. Many of the manuscripts in question come from the Mainz Charterhouse, founded in 1320 as first in the Rhineland area, and are part of a group of 89 such objects being digitised by the Bodleian Libraries. More information about the project can be found here.

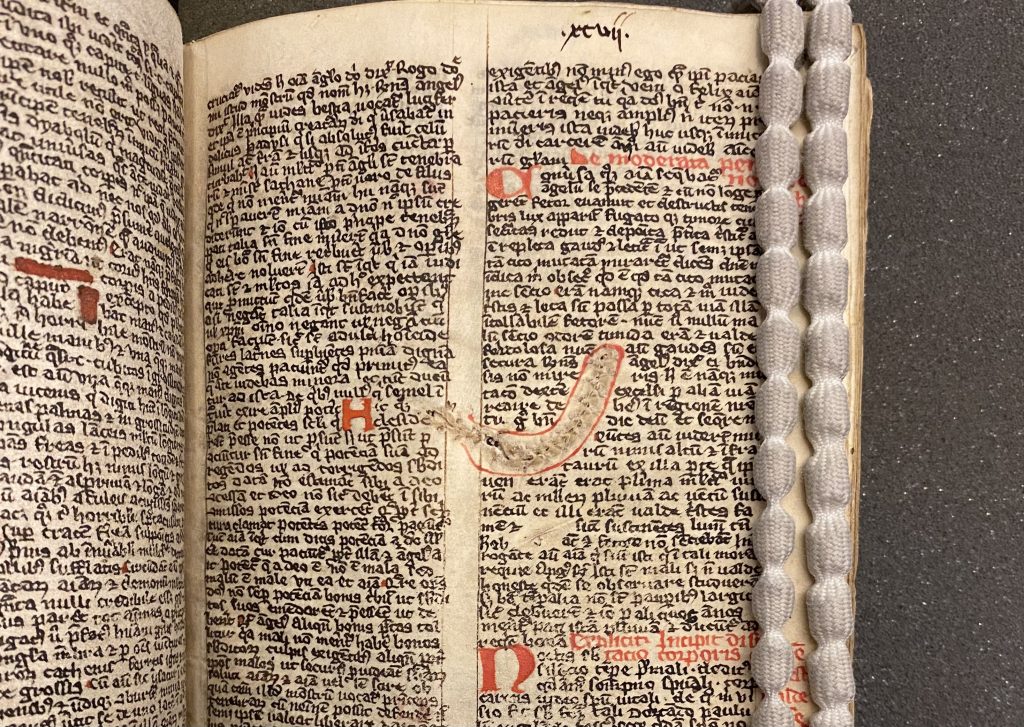

Laure’s introduction began with a whistle-stop tour of typology. Firstly, that there exist three primary categories of scripts: Textualis, Cursiva and Hybrida. Textualis is the most calligraphic, consisting of fully formed, upright letters that are distinct from one another. Cursiva is (as the cognate tells us) much more cursive and its letters are joined together to accelerate the process of writing. Finally, Hybrida does what it says on the tin – these are scripts which incorporate both aspects of Textualis and Cursiva, both calligraphic and flowing at the same time. While Gothic scripts often seem unintelligible to the modern eye, Laure gave us the key to their deciphering through three unmistakable shapes of letters. These are the letter ‘a’, which either appears in two compartments (with a quasi-ascender above the main body of the letter); letters ‘s’ ‘f’ and ‘straight’ characters, which appear either with or without a tail under the line; and the shapes of ascenders and descenders, normally shorter or forked in Textualis script, and looping in more cursive examples. Within these categories there also exist differing levels of execution: Formata, the highest quality execution, Currens the least adorned execution usually compared to modern day ‘handwriting’, and Libraria sitting neatly in the middle as the half-and-half method employed usually in university settings. To help us wrap our heads around all this jargon, we then moved from our desks to gather round Alison’s table of manuscript wonders to see some script in action.

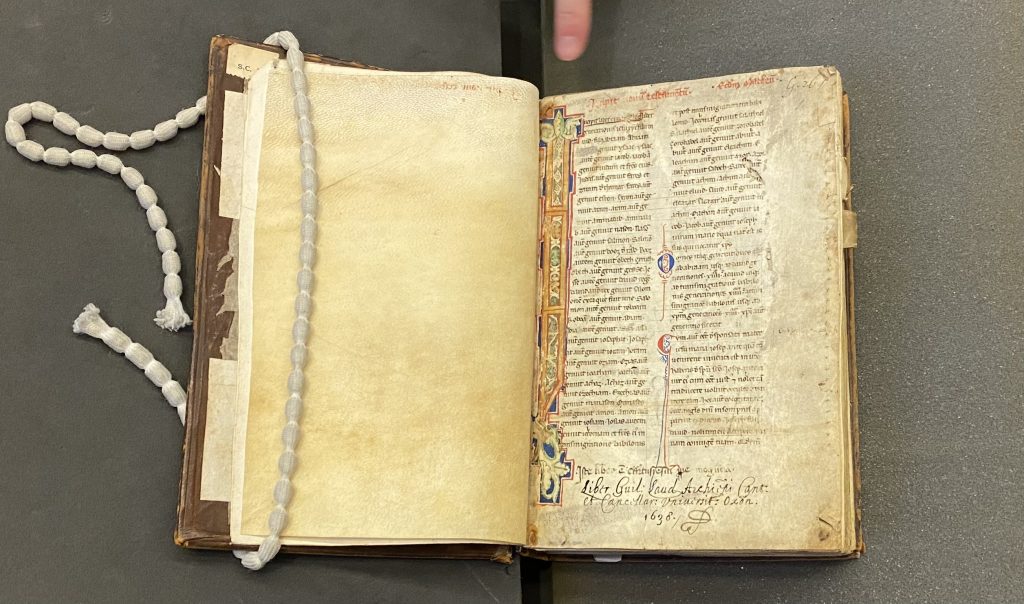

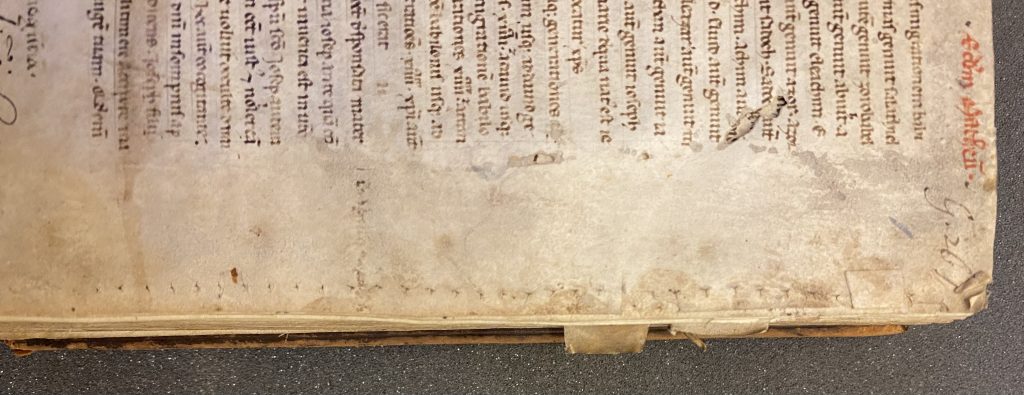

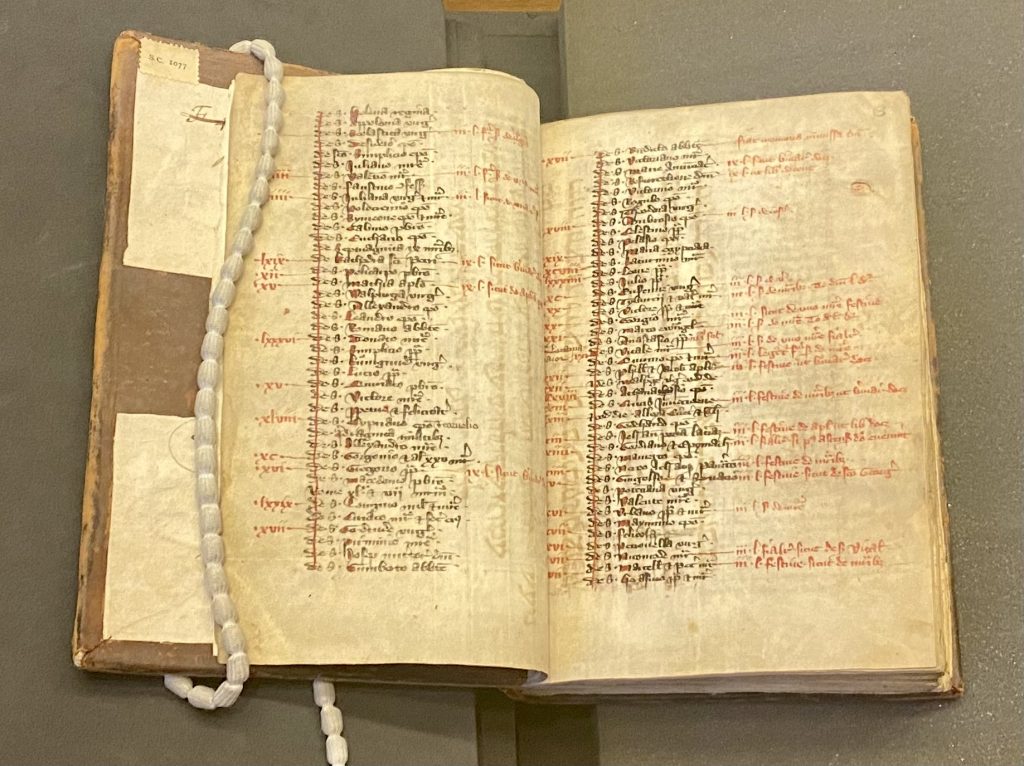

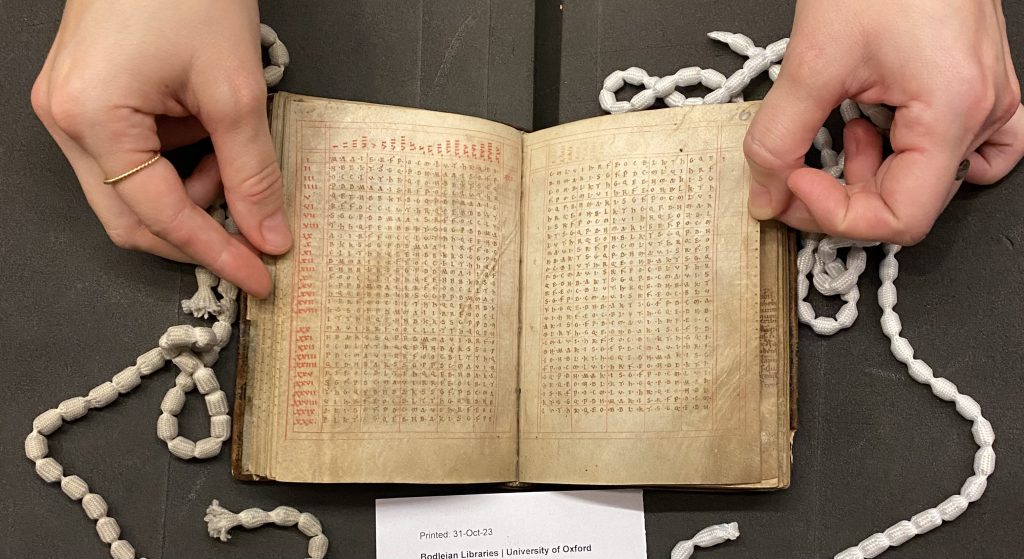

Looking first at MS. Laud Lat. 102 , we saw as many as five hands (that is, examples of handwriting or script production) contained within one manuscript! The codex itself was a 9th century Gospel Book containing canon tables on fols 1r-8v used to find and compare the same passage within separate gospels, as well as eye-catching red monumental capitals and examples of script from German Anglo-Saxon minuscule to Carolingan minuscule. We looked at MS. Laud Lat. 24 in the same vein and saw that as well as displaying decorated initials and reading guides to the chapter headings and numbers in early Italian Textualis script, the paper was also marked by a series of small holes along its edges, which led us neatly onto the next section of the class…

Assembling the Codex! Laure then explained to us the ins and outs of various writing surfaces, papyrus, parchment, and paper. We learned of the differences between calfskin, sheepskin and goatskin when making parchment, the existence of pricey, dyed ‘purple manuscripts’ such as MS. Canon. Liturg 287, and the ways in which defects or lacunae and even mistakes by the scribes can be remedied. With Alison, we then saw examples of these features in MS. Laud Lat 102, rebound by the Oxford conservation team in 2016 using treated leather, natural fibres and preserving the original wooden boards from its first binding in the 9thcentury. Further examples were fascinating: MS. Laud Misc. 352 gave contained a palimpsest, or rather a piece of parchment where original text has been artfully scraped off with a knife in order to superimpose next text. The original text, still visible despite tampering, is tentatively identified as an excerpt from the Qerovah for Yom Kippur morning, and the superimposed text is a Mainz Charterhouse-composed account of saints’ lives. MS. Laud Misc. 315 was an example of where a fault in the parchment (often caused by over-stretching or injury on the animal’s skin) had been sewn up and even highlighted by a red outline. Of particular interest was the watermark found within MS Laud Misc. 116. With help from a backlight, Alison made mythical beasts appear within the walls of the Weston Library when she lit up the unicorn contained within the codex!

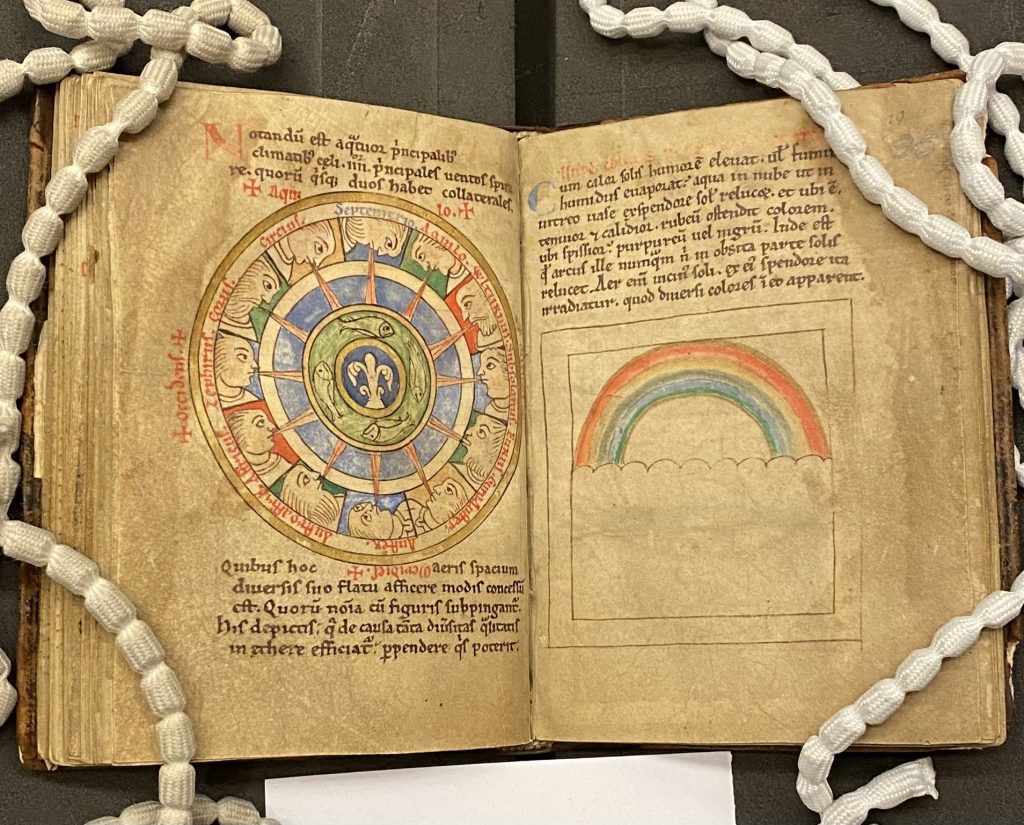

Finally, we ended up where it all started, and Laure gave us a brief history of script itself. We first learned about script inherited from the Romans, such as Capitalis (or rather, ‘capital letter’ script as we would understand it today) and Uncial, letters that are ideally an inch high and more calligraphic. Moving onto the study of insular scripts, we saw how scripts inherited from Roman society often evolved within smaller geographical locations, and then took Caroline minuscule, which from c.850 was the usual script of the Carolingian empire in Europe, Protogothic script, and Textualis Rotunda as case studies. No stone was left unturned in Laure’s palaeographical presentation and gave us much food for thought to then apply to Alison’s final few manuscripts. These examples were the perfect way to wrap up three hours of palaeographic perusing. The class-favourite manuscript was MS. Bodl. 614, a 12th century English manuscript containing a version of the “Wonders of the East”, a prose text detailing and illustrating all manner of mythical and legendary creatures, from elephants to phoenixes. A calendar for calculating the date of each year was seen in tiny script at the start of the codex, and Alison went on to show us her final favourite image: a simple rainbow. Who knew a small illustration from 900 years ago could still work to brighten up the rooms of the Weston Library?

A huge thank you must go again to Dr Laure Miolo and Dr Alison Ray for taking the time to dive into the palaeography with us this Wednesday afternoon, it was a session we certainly won’t forget.