By Edie Young (MSt in Modern Languages)

Last week, History of the Book students had the rare opportunity to examine Merton College’s collection of mediaeval astronomical instruments, which were exceptionally out of their cases. Dr Laure Miolo gave a dazzling presentation on mediaeval astrolabes, equatoria, quadrants, and astronomical manuscripts. Laure brought her very own replica of a c.1400 astrolabe, which added an interactive element to the session. With this tactile aid, we were able to more closely examine the inscriptions and mechanisms involved.

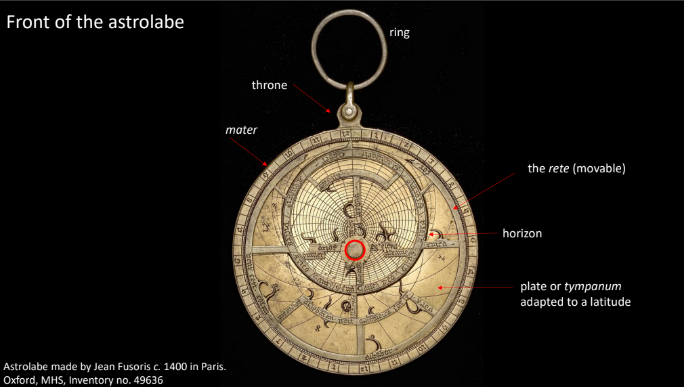

The astrolabe is a two-dimensional celestial globe, used for both astronomical and astrological purposes, that dates back to the Hellenistic period. From the late 10th century, astrolabes were used in Europe for a variety of purposes. These include:

- Telling the time

- Celestial navigation (determining the observer’s latitude from the meridian altitude of the Sun or a star)

- Finding the position of celestial and planetary objects

- Determining the length of a day

- Drawing astrological charts

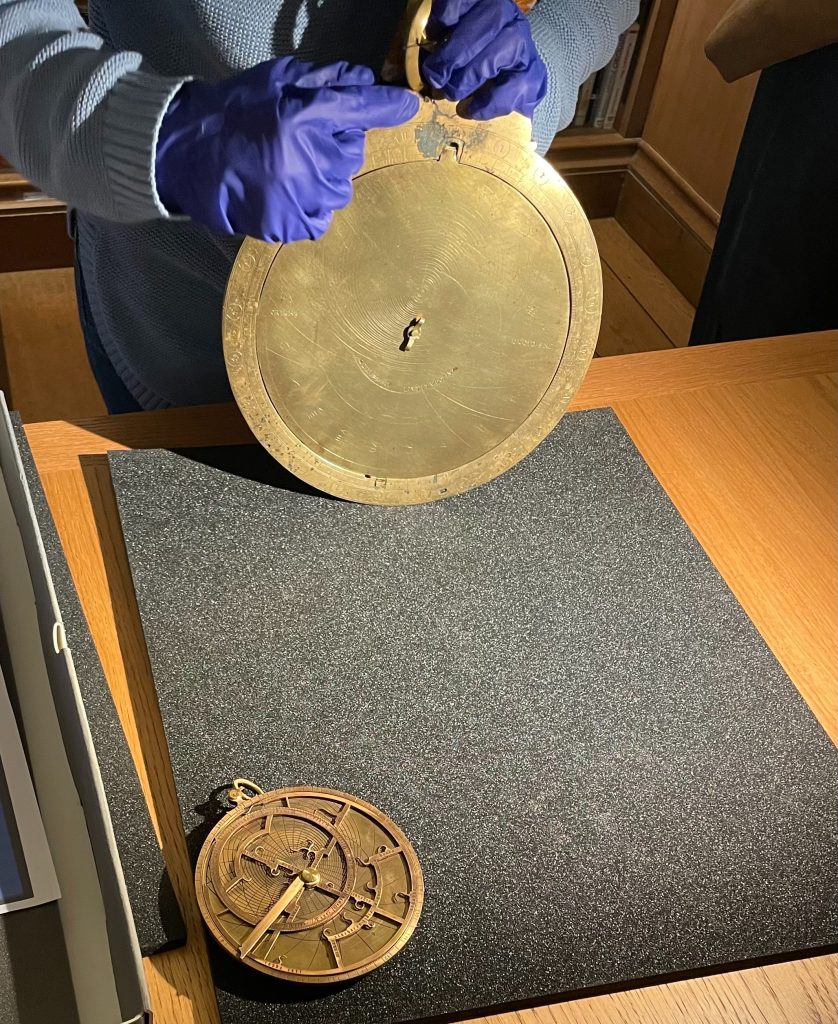

The first instrument Laure presented was a very large 1390 astrolabe. The above photo shows its vast size compared to the demonstration astrolabe. It was missing its rete, a rotatable star chart, and its alidade, a sighting device which aligns the astrolabe with celestial objects in order to read their latitude. The instrument had been re-engraved at some point, and its throne (the part at the top where the ring is attached) had double suspension, an Islamic characteristic that provides extra support. Interestingly, this astrolabe had a lunar disk added to the back, which allowed observers to measure the latitude of the Moon, aiding timekeeping and navigation.

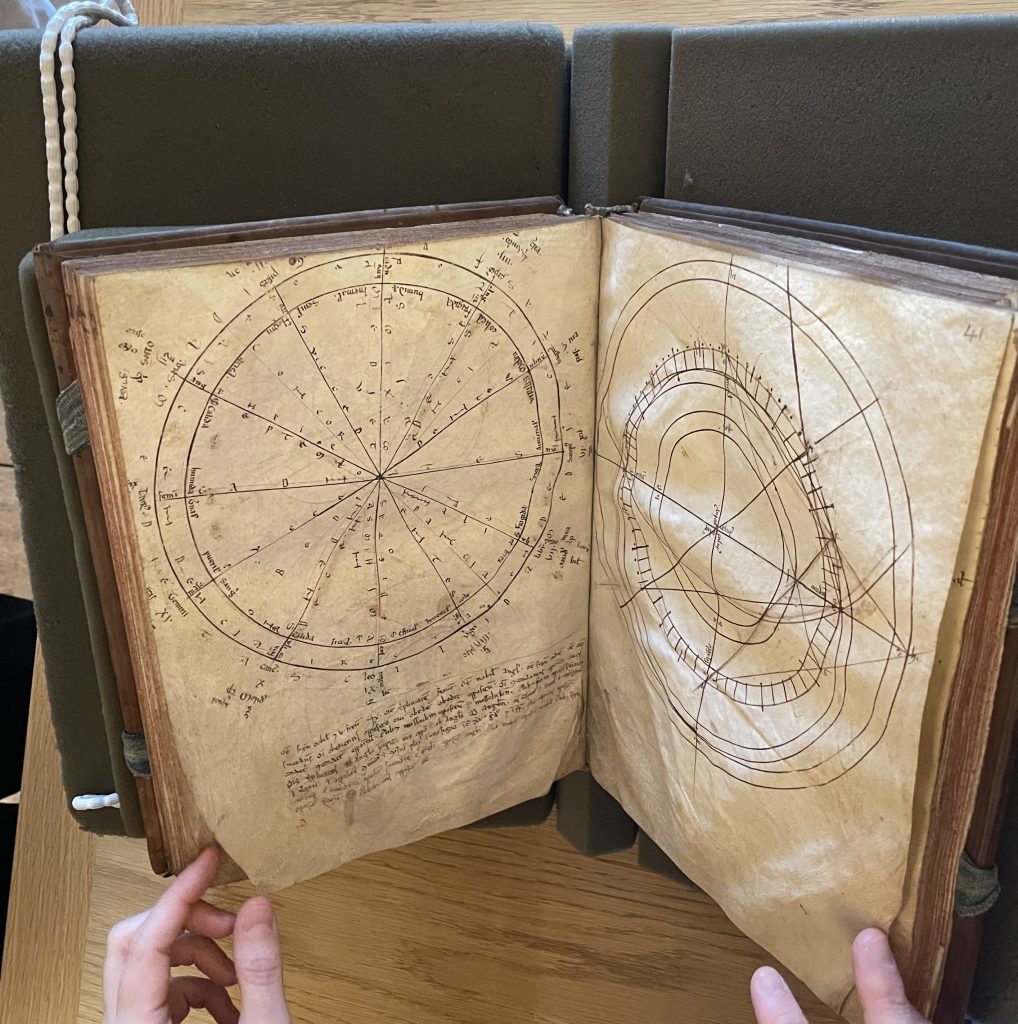

Next, Laure showed us the Merton Equatorium, the oldest surviving equatorium in the world, dating to c. 1350! Its tympan, a (commonly) removable plate made for specific latitudes, was fixed, adapted to the latitude of Oxford, or Oxonia, which was particularly exciting! While astrolabes are used to measure astronomical bodies at specific locations, equatoria can be used to calculate past and future positions of planetary, lunar, and celestial objects. The Merton Equatorium has 32 stars on its rete (above left), and the motions of the seven spheres are displayed on its back (above right). The seven spheres are arranged around the stationary Earth, and correspond to the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, respectively, as can be seen in the photo. The back also houses a table showing a century’s worth of variations of the eighth sphere, used to make adjustments for the precession of the equinoxes: the gradual shift in the orientation of Earth’s axis.

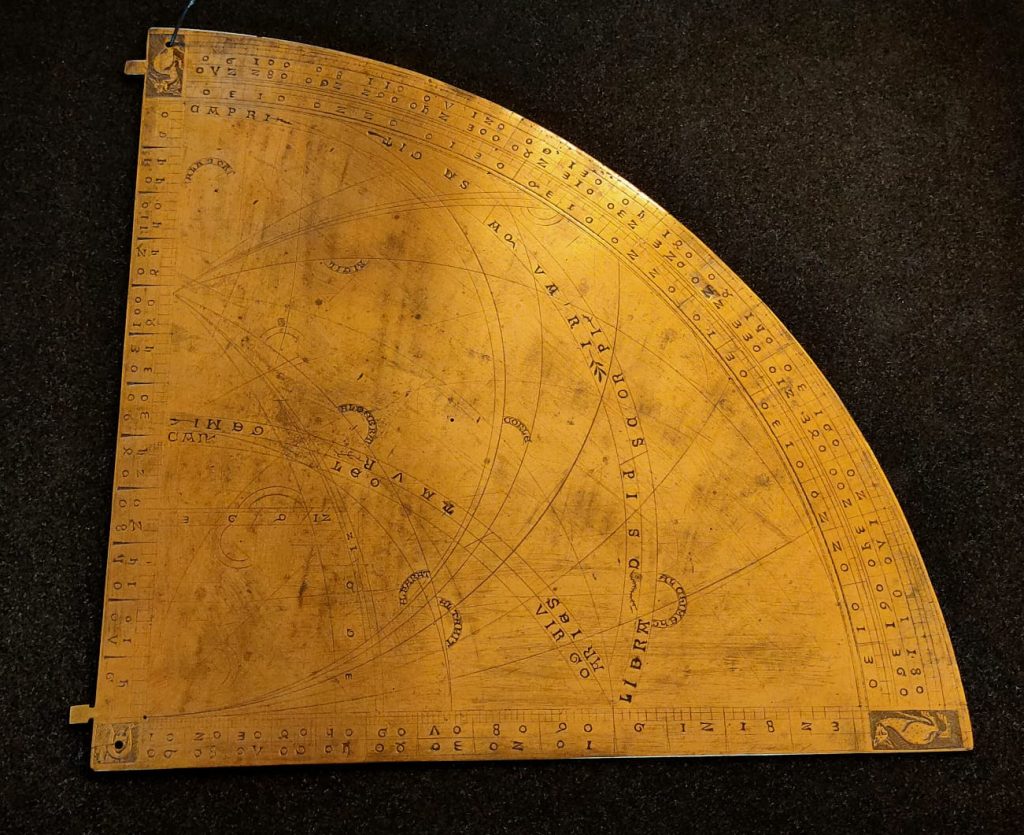

We looked at the Profatius Iudeus Quadrant, an instrument which condensed the workings of an astrolabe into one quarter of the size. Laure drew our attention to the ornamentation in its three corners, signalling the astronomical knowledge of the owner, who recognised that the corners were not needed for calculations. The first corner (bottom right) was ornamented with a hind, the second (top left), another hind carrying a leaf-spray in its mouth, and the third (bottom left) was a rebus consisting of the hinds’ missing legs and a fleur-de-lys.

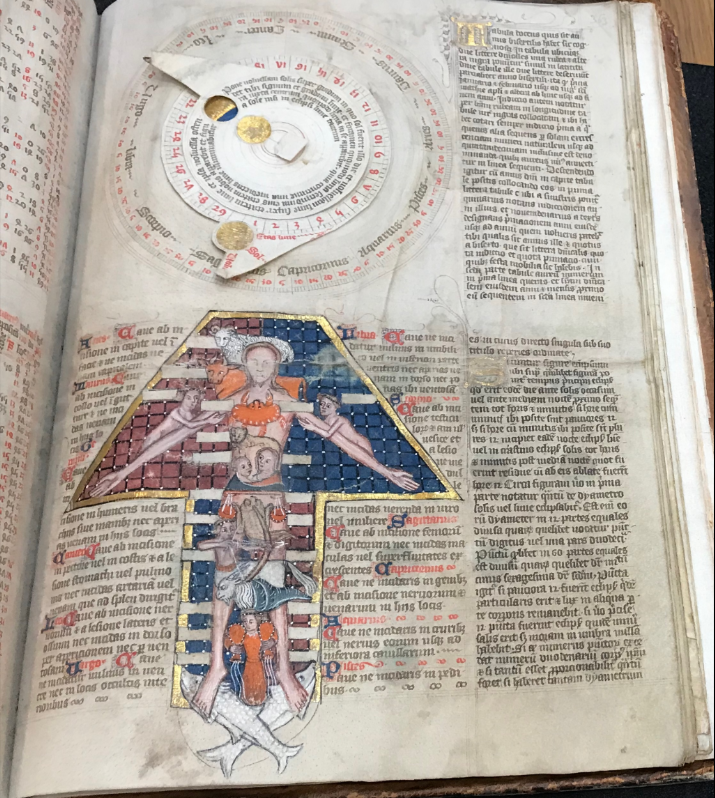

My favourite instrument was the Physician Quadrant. This quadrant was initially dated around 1400 but may have been made earlier, according to the latest analysis. Robert Gunther, the founder of Oxford’s History of Science Museum, affirmed that it was constructed at two different points in time. The back includes two rotating disks and two pointers for marking the positions of the Sun and Moon (believed to affect the world more strongly than other astronomical bodies) to calculate their placement in relation to the Earth. These luminaries were essential for physicians, who would consult their positions to assess patients and determine the best time for treatment. Similarly, the Zodiac Man depicted on the front dictated when to administer treatment. Above all, procedures should not be performed on body parts when the Moon could be found in their corresponding sign.

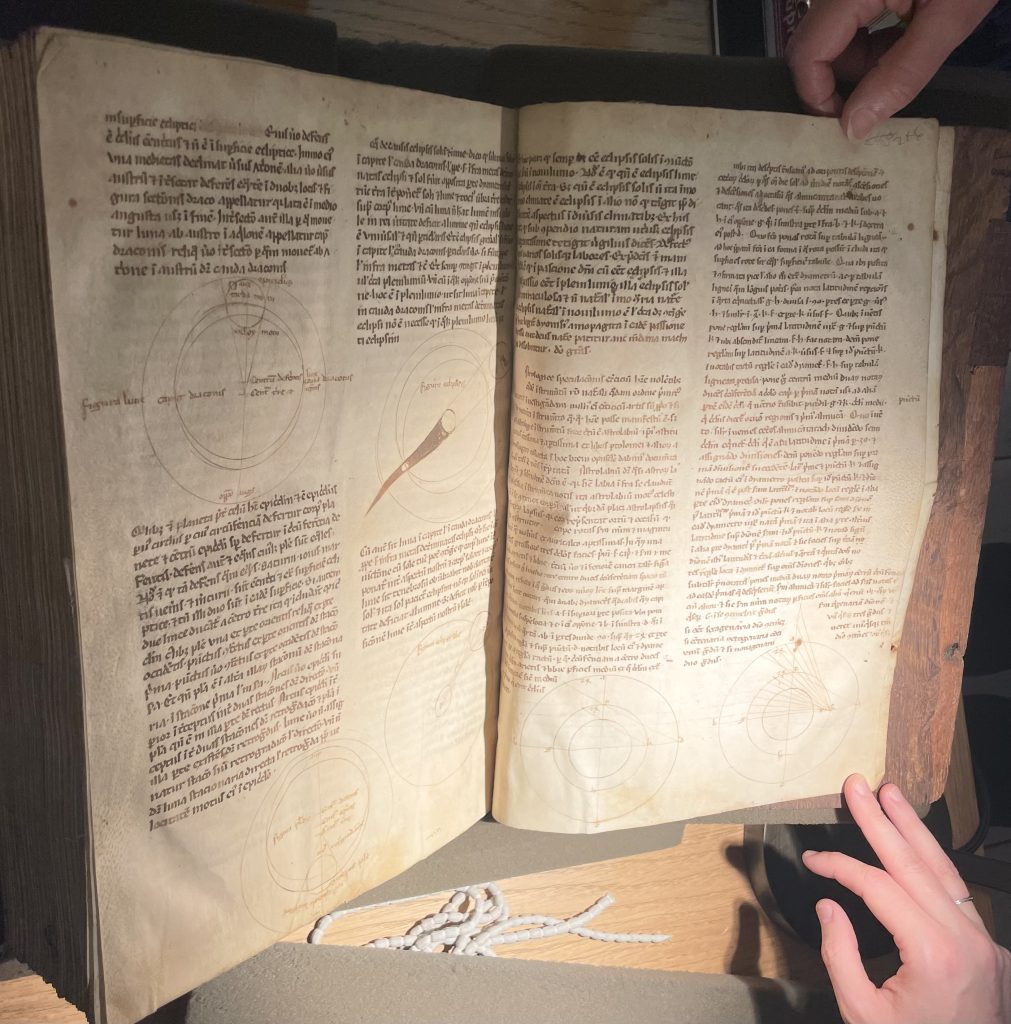

Laure then showed us two astronomical manuscripts, the first, dating to the 14th century, was chained at some point during its history. The first part of this text was a collection of Augustine’s theoretical treatises, while the second part was a copy of a Southern French astronomical textbook, including notes on the composition of the quadrant and diagrams of astrolabes.

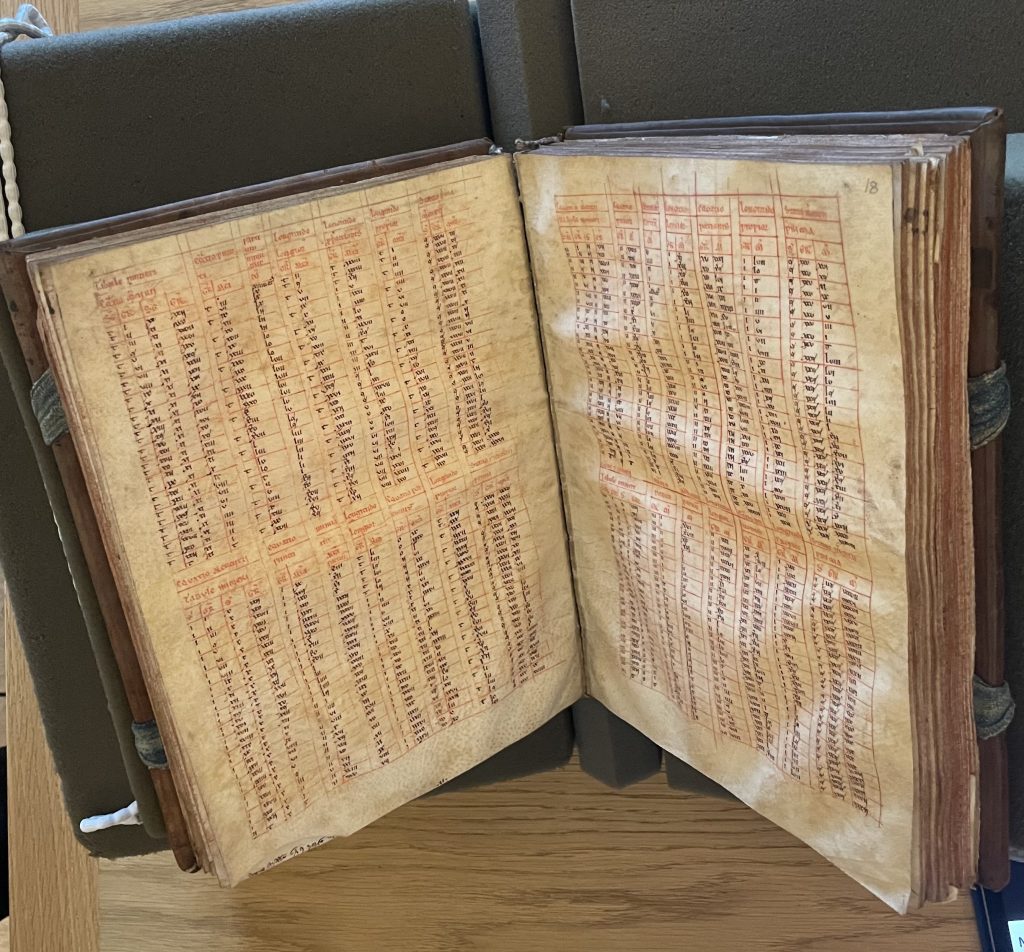

The final manuscript (c.1200) comprised two parts bound together by William Reade, a mediaeval astronomer. Its first section included a copy of the Toledan Tables; mathematical tables, completed in around 1080 by astronomers in Toledo, used to predict the movement of celestial and planetary bodies. These tables were accompanied by astronomical diagrams and depictions of astrolabes. The second half was a collection of texts relating to the astrolabe, and both astronomical and astrological texts translated from Arabic into Latin.

I saw this session not only as a rare opportunity to examine these fascinating astronomical instruments, but also as an example of the History of the Book’s cultural and scientific breadth. Orbiting art, astronomy, literature, palaeography, mathematics, history, and medicine (to name just a few!), Laure’s session pays testament to the varied and interdisciplinary nature of the History of the Book.