By Ksenia Dugaeva

In our ‘Structures of the manuscript book’ seminar last week, we continued our foray into understanding how manuscripts come together – focusing in this session on the journey from sheet to codex to bound book.

All of us browse, read, and generally handle books in our daily and academic lives, and a few of us are perhaps aware of the details of how these objects are put together – though the first half of this workshop, led by Matthew Holford, made us confront this intricate process. Having learnt about parchment production in the last session, we were now guided through how four full or half-sheets of parchment (and later paper) can be folded together to form a quire. Due to the uneven texture of parchment – which, due to its animal origins, has a ‘hair side’ and a ‘flesh side’ – there are two approaches to folding the quires: in continental Europe, parchment was folded so that hair side would face hair side when the MS is open, whereas scribes from the British isles favoured the ‘insular’ method of arrangement, wherein the parchment sides would alternate, with hair side facing flesh side and vice versa. Following folding, and prior to writing, scribes would fasten the quire temporarily (a process known as quire tacketing) and then number the quires to keep them in order before assembly and binding. We were introduced to ‘catchwords’ and leaf or bifolium signatures, which were used to number sheets in alphabetical numerical sequence.

The knowledge and awareness of these systems allows us to be able to spot ‘mistakes’ or inconsistencies in quire structures – are there any leaves missing or have any been added? Are there any ‘singletons’ (folded leaves that are missing their second half)? These details can point us towards the decisions made by the scribe, with regards to the placement of extra text or inserted decorative elements, and help us raise questions about how and why a certain MS was put together.

In the second half of the workshop, Andrew Honey gave us a thought-provoking overview of binding. Book binding, which is often thought of as mainly decorative, plays a crucial role in making a book readable – protecting the leaves and, most importantly, keeping them in order, as until the MS reaches the book binder, none of the sheets are fixed in place. We focused firstly on the technical details and varying structures of binding and were introduced to the main two styles: Romanesque and Gothic. The main difference between the two can be seen in the way the sewing supports are laced to the board – while in Romanesque binding the supports are laced through the back edge of the board, in Gothic binding the lacing is done over the back edge of the board. Consequently, Romanesque binding allows for a flatter spine.

Further, we were able to observe the differences between personal and institutional bindings. During this term, we have encountered many impressive(ly) large volumes, complete with illustrations and illuminations, as well as intricately bound manuscripts – including ones exhibited in this session, for instance MS. Bodl. 700 with its tawed chemise, or the overwhelmingly beautiful velvet-bound manuscript Barlow 28.

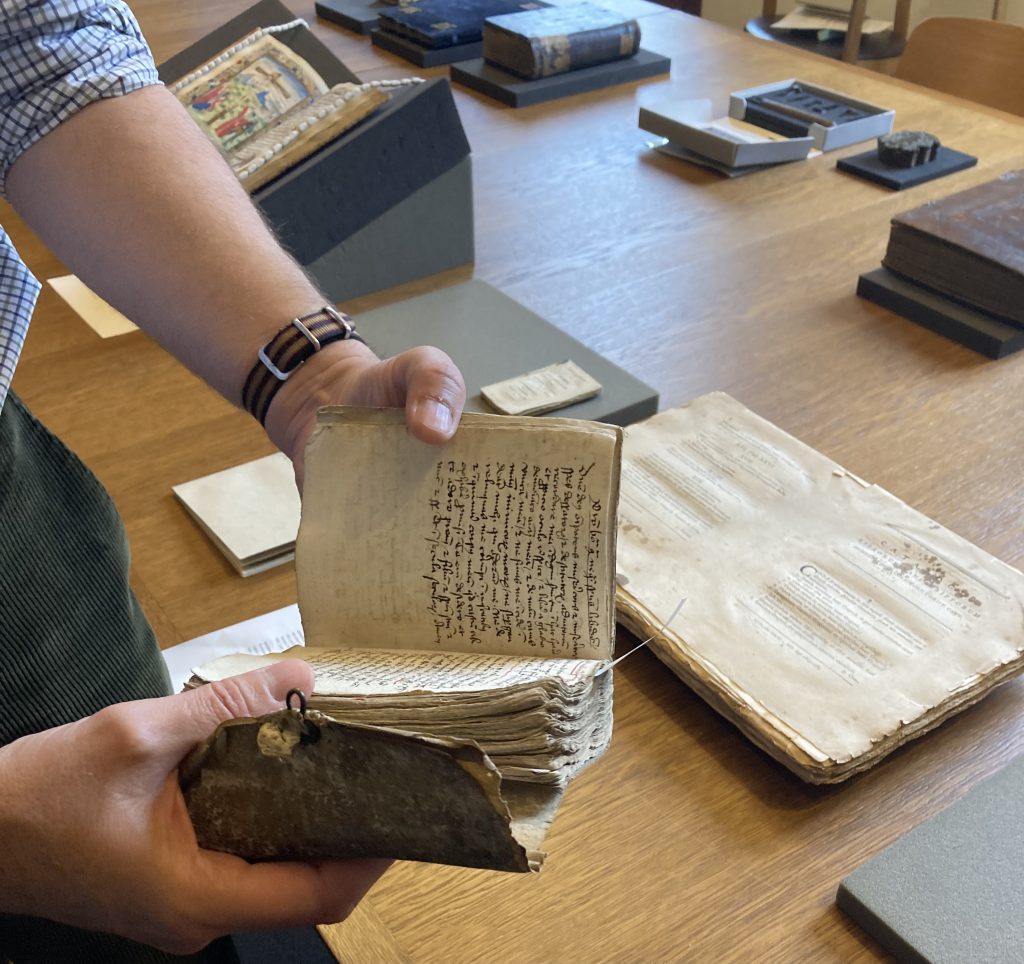

I was particularly drawn to the almost pocket-sized MS. Don. e. 250. A devotional compilation from Western Germany, from the latter half of the fifteenth century, this manuscript was bound for personal use, with its well-worn limp binding and clasp bearing witness to extensive use. This MS is a rare survivor, as we were told that the bindings more likely to stand the test of time (especially those that date back to the Medieval period) are usually institutional.

Above all, we were invited to consider book binding as a moment in time. Analysing the binding can reveal important information about a book and its history. If a medieval manuscript has more modern binding, it must have been worth spending money on – was a new proprietor or institution splashing the cash? and why? Manuscripts are often rebound to fit into an institution’s binding style; there are also finishing tools with various decorations (boasting exquisite seashell ornaments, etc.) that are used on bindings commissioned by certain collectors. These markers, alongside inscriptions on title pages, can be instrumental in tracing a book’s journey through time and place.

Introducing us to fascinating technical processes and details, this workshop armed us with further tools and encouraged us to continue our examination of manuscripts as material objects, each with its own history and future.