by Charlotte Ross

Manuscript decoration enhanced the appearance of a text, increasing the value of the book and bringing a sense of status. The most illustriously decorated manuscripts ooze wealth and sophistication, acting as a statement of the owner’s importance. Even within the manuscript itself, these decorations establish a hierarchy amongst the text, identifying the most relevant sections by framing them in an array of colours and designs. For this reason, the first folio is often the most decorated and ornate of the manuscript. Border decoration also provides structure for the text, signalling the start of new chapters or texts within a manuscript and navigating the reader through the book. They also make the act of reading easier, providing a rest for the eyes and aiding concentration.

However, sometimes there is more to these border decorations than meets the eye. Two beautiful manuscripts in the Bodleian’s collection feature delightfully decorated borders and initials that go a step further than their function: they have messages hidden within them.

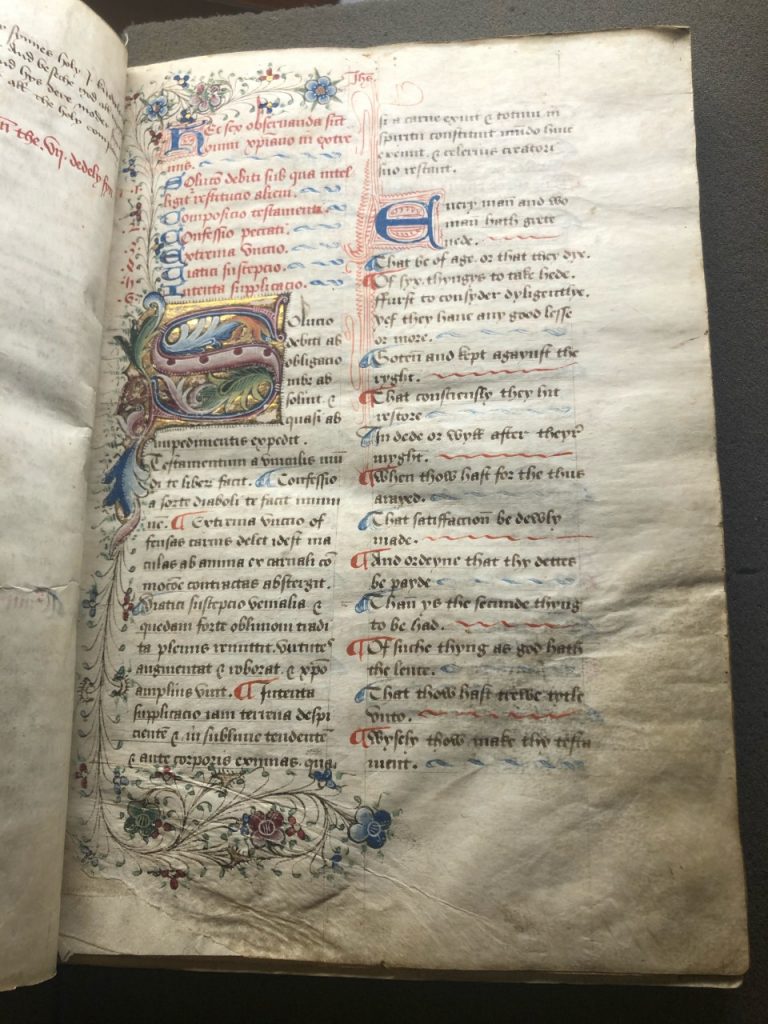

Firstly, we turn to MS Douce 322: An English manuscript from the 3rd quarter of 15th century. It contains a collection of seven texts, ranging from religious treaties to German mystic texts. One of these texts is a series of lessons by Richard Rolle of Hampole, entitled ‘The nyne lessons of the Dirige whych Job made”. On fol. 18r, we find the start of the last of these lessons, which opens with the Latin maxim “Hec sex observanda sunt omni cristiano in extremis” (These six are to be heeded by all Christians at the point of death), followed by an expansion in English verse.

The large decorated initial S on this page is adorned with spray vines that extend along the gutter and curve round the corners of the text, framing the start of the lesson. This spray style is typical of this period in English manuscripts, and at first glance this page seems fairly usual.

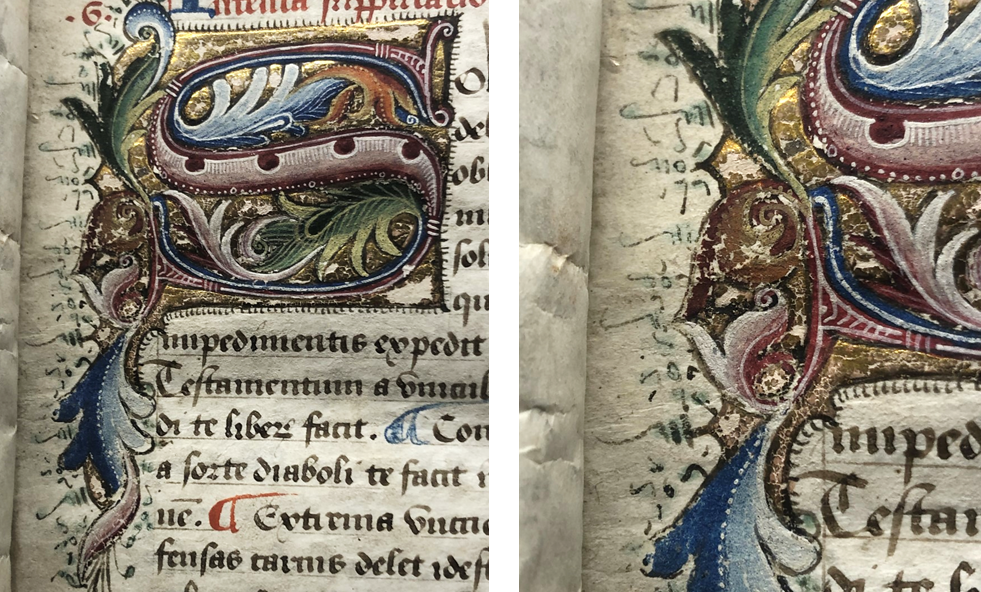

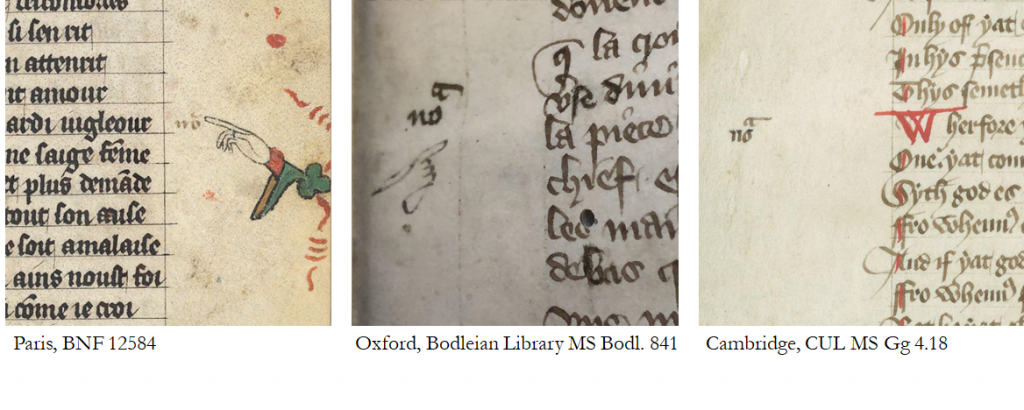

But when you look closer at the initial S, along the left side down the gutter we see some interesting curved flourishes, which look like the letters nō stacked vertically. These flourishes closely resemble an abbreviation used in marginal annotation for ‘nota’. This abbreviation can be seen dotted throughout manuscripts to mark important passages that require ‘nota bene’ – observe carefully. This symbol was widespread in medieval manuscripts and certainly would have been recognised by literate audiences at the time.

Drawn in the same ink as the stems of the vines that curl around the text, it is reasonable to conclude these miniature nota’s were drawn with the rest of the border. They serve a dual purpose here, as both decorative flourishes which add to the overall drama of this title page, but also as a note to the readers – “take note this is important!”.

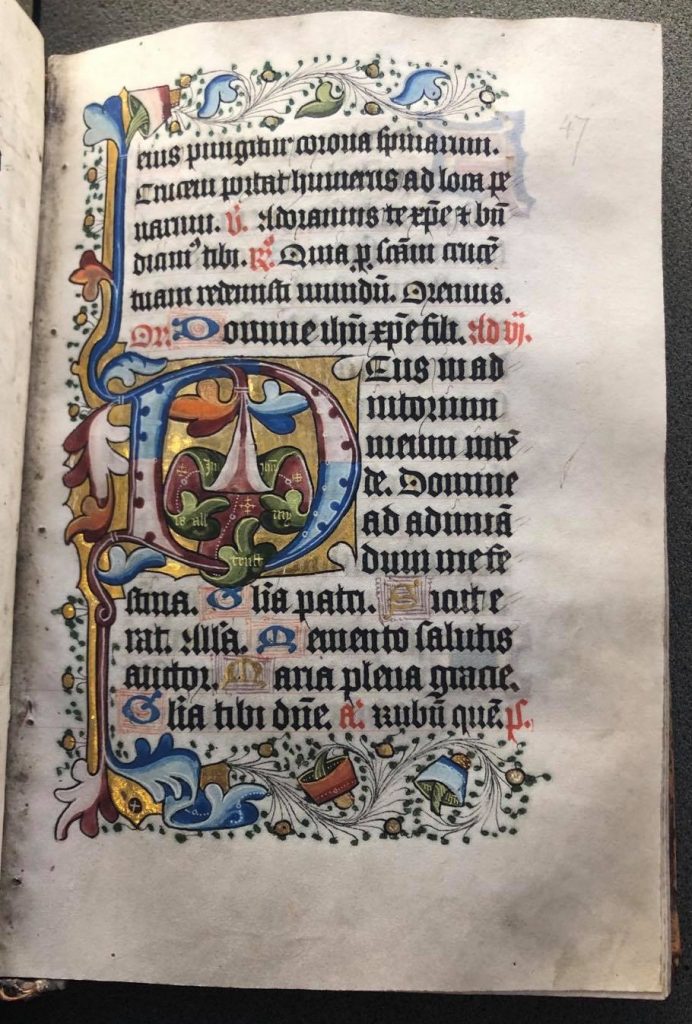

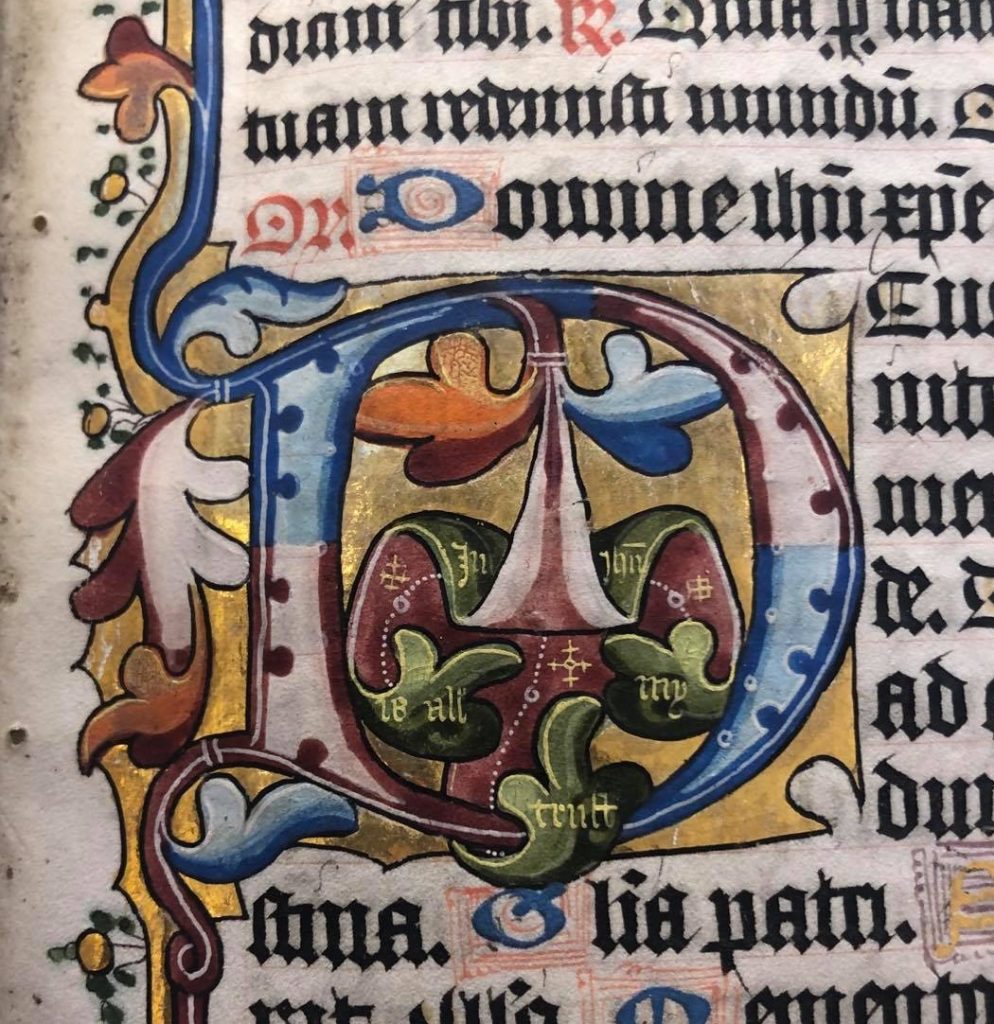

Another manuscript in which we find hidden words is at MS Rawl Liturg. e. 3, a Book of Hours in English and Latin from the first half of 15th century belonging to the diocese of Norwich. This is another fine example of an elaborately decorated manuscript with floriated borders and similarly intricate decorated initials. The style is in keeping with Books of Hours of this period, featuring rambling vines, decorated initials and miniatures of various saints which act as “painted prayers”.

This manuscript also features hidden words entwined into its borders, in this case hidden within the letters themselves. Fol. 47r shows an illuminated initial D in vibrant colours picked out in gold. Nestled within the leaves is written in white ink ‘In jhū is all my trust’ (In Jesus is all my trust).

This letter D opens a Gradual Psalm, Psalm 69 (in the Vulgate), which begins ‘Deus in adiutorium meum intende’ (God reach out to help me). The hidden scroll declaring trust in Christ therefore is in keeping with the surrounding text, as if it were a response to the Psalm. It is also reminiscent of the evensong O Lord in thee is all my trust by Thomas Tallis, which was contemporary to this Book of Hours and likely familiar to it’s reader. As a text designed to aid religious devotion and guide the reader’s worship, an allusion to a hymn is not surprising. Usually, when hymns are referenced in manuscripts, the first few musical notes of a song are written on a stave to prompt the reader’s memory. Could this hidden devotional message serve a similar purpose?

It could equally be read as a personal motto. Whilst Books of Hours were not always made for specific individuals, a book with this quantity and quality of decoration could have plausibly been commissioned. In this case, inserting a personal motto into a prayer would be comparable to placing one’s coat of arms or initials on the page.

Incorporated into the initial that opens this prayer, rather than as a note in the margin or built into the text, we are clearly meant to read this phrase before embarking on the prayer. The placement of this message is quite literally shaping the way we read the text. Yet if you consider this from a more symbolic point of view, by hiding these messages inside initials and within borders, the manuscript is encouraging us as readers to look closer and scrutinise the text. Just as Books of Hours were used to inspire devotion and reflection, the physical manuscript is encouraging us to read deeper into both the physical book and the religious texts themselves.

The hidden words buried in the border decoration of these 15th century codices are but a small example of the beautiful nuggets unearthed when we are allowed the privilege of working directly with manuscripts. Were these texts to be transcribed and printed in a modern edition, these details would certainly not be included alongside the text, possibly merely relegated to a footnote. But they remind us of the precision and deliberation involved in manuscript production. Every detail, from the choice of ink to the design of initials to the limner’s decoration was considered and had a function. Whilst not every detail should be read as symbolic, these hidden words prompt us to consider these manuscripts as both works of literature and art, a beautiful crossover which both directs our interpretation and encourages us to think beyond the physical book.

Charlotte Ross is a first year MPhil student in medieval literature at the University of Oxford, and a member of St Cross College.

https://www.instagram.com/medieval_bookworm/

Further Reading

For further research on decorative hierarchies, see Kathleen L. Scott, ‘Design, decoration and illustration’ in Book production and publishing in Britain 1375-1475, ed. by Jeremy Griffiths and Derek Pearsall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

On decoration as a cognitive experience, see Juliet Fleming, “How to Look at a Printed Flower”, in Word & Image (London. 1985), vol. 22, no. 2 (2006) pp. 165–187.

A more detailed break down of the abbreviations of ‘nota bene’ can be found in William Schipper’s chapter ‘Textual Varieties in Manuscript Margins’ in Sarah Larratt Keefer and Rolf H. Bremmer, Signs on the Edge : Space, Text and Margin in Medieval Manuscripts, (Paris: Peeters, 2007).

For further research into decoration in Books of Hours, see “Patterns of Desire”, in Piety in Pieces: How Medieval Readers Customized Their Manuscripts, by Kathryn M. Rudy (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2016).

29 thoughts on “Hidden in Plain Sight: Secret Messages in Manuscript Marginalia”