By Philip Flacke

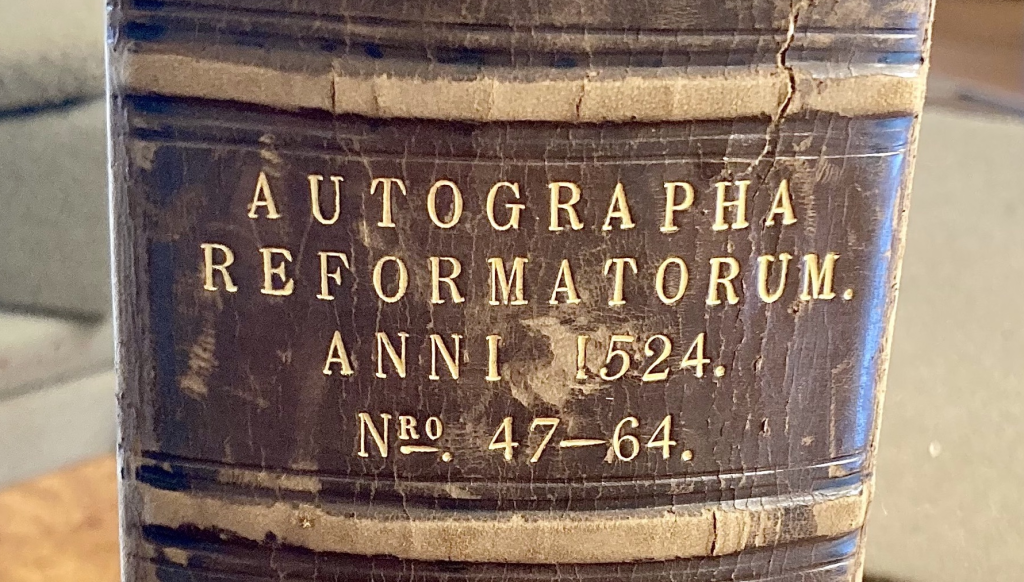

This is part of a series of introductory posts for the updated edition and translation of Hans Sachs’s first Reformation Dialogue ‘Chorherr und Schuhmacher’ (‘Canon and Cobbler’) in German (1524), Dutch (1540s), and English (1540s), published as Volume 5 of the Treasures of the Taylorian. Series One: Reformation Pamphlets. Ebook of the publication.

- The Historical Context (Tom Wood)

- English Reformation Dialogues (Jacob Ridley)

- The Pamphlets in Oxford (Philip Flacke)

- The Edition including the Bibliography (Henrike Lähnemann)

Related Taylor Editions

- Hans Sachs: Disputation zwischen einem Chorherren und Schuhmacher (1524)

- Een schoon disputacie (the Dutch translation of the early 1540s, coming soon)

- A goodly dysputacion (the English translation of the 1540s)

- Hans Sachs’s other 1524 dialogues (coming soon)

The Reformation in sixteenth-century Germany was a matter of public debate to a scale that had never been seen before. It was carried by a generation, born between 1470 and 1500, whom Thomas Kaufmann has recently characterised as ‘printing natives’ in analogy to the digital natives of today.1 These women and men had grown up with the new technology of printing with movable type and the resulting emergence of a media landscape fit for the fast and cheap circulation of ideas. Hans Sachs was one of them. His Reformation dialogues from 1524 reflect on what it meant to partake in a heated public debate. The pamphlets in which these texts reached an audience all over the German-speaking world provide an insight into media use not just by Sachs but by printers, booksellers, readers, collectors, politicians, and the ‘gmaine mann’ (edition, a2r: common man and woman!) addressed in his pamphlets.

Printing Reformation pamphlets

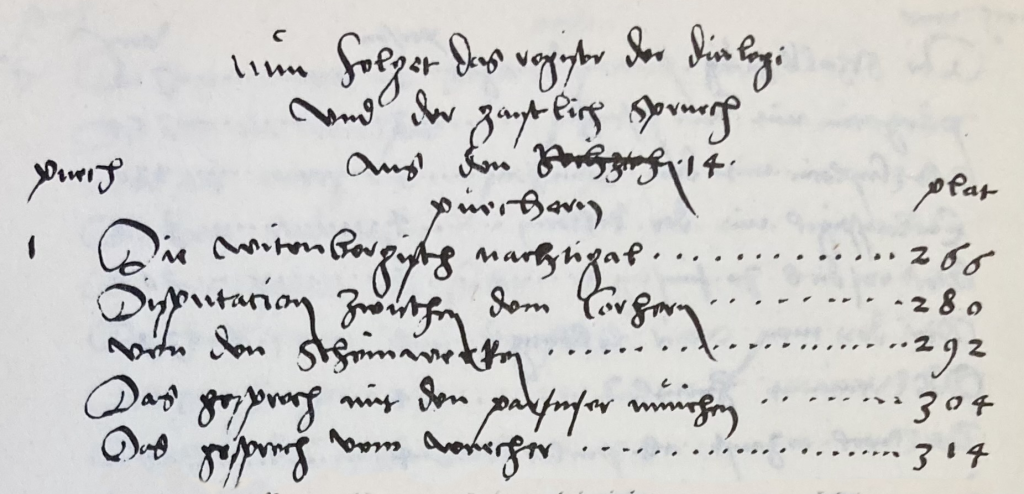

Four of Sachs’s prose dialogues have an 1524 imprint date. No autograph of any of these exists. This is despite the fact that Sachs copied out more or less all of his literary output by hand into what eventually grew to be 34 volumes. Two indices, compiled by Sachs himself later in life, contain the folio numbers of where the four dialogues were to be found in the very first of these volumes.2 But this volume, compiled in 1526/27, has not survived. In the second of these two indices, written half a lifetime after their publication, Sachs lists the four texts under the following short titles: ‘Disputation zwischen dem Corhern’, ‘Von den scheinwercken’, ‘Das gesprech mit den parfuser munichen’, ‘Das gesprech vom wuecher’. Even if the exact order in which they were written and published, has been a matter of academic debate,3 it is clear, that the ‘Chorherr und Schuhmacher’ comes first.

On publication the Disputation zwischen einem Chorherren vnd Schuchmacher was an immediate success. Printers in seven cities published no less than 13 editions, all dated to the year 1524: three in Bamberg, four in Augsburg, one in Speyer, one in Erfurt, one in Eilenburg near Leipzig, one in Straßburg and two in Vienna.4 While the Wittenbergisch Nachtigall had first been published anonymously, the name Hans Sachs now appeared on all these editions. – All except one: The printer Matthes Maler in Erfurt got it wrong and typeset on the title page: ‘Hanns Bachs’.

Nuremberg is noticeably missing. As had been the case with the Wittenbergisch Nachtigall (Ill. 3) in the previous year,5 Sachs did not publish his text in his home town but turned to the printer Georg Erlinger in Bamberg instead – probably because of the difficult situation for printing and selling pamphlets in Nuremberg at this point. We know of the case of an old woman who was living in the Tuchscherergasse (‘[d]as alte Fräulein im Tuchscheerergäßchen’).6 After she had offered copies of a newly printed pamphlet by the reformer Heinrich von Kettenbach for sale, she had to spend four days and nights chained to the pillory. This was in January or February 1524 – precisely when Sachs might have worked on his first dialogue.

Only one further German edition from the sixteenth century is known, published around 1580.7 All of Sachs’s 1524 dialogues were bestsellers but not longsellers. When later in his life Sachs compiled an edition of his own collected works, which was published in five large volumes in folio from 1558 to 1579, he did not include the four Reformation dialogues. The Dutch and English translations included in this volume were almost certainly printed without Sachs’s involvement. More than two decades after the original publication, they testify to an interest in the text by new audiences and to their potential for new markets.

Strong emotions: sixteenth-century readers

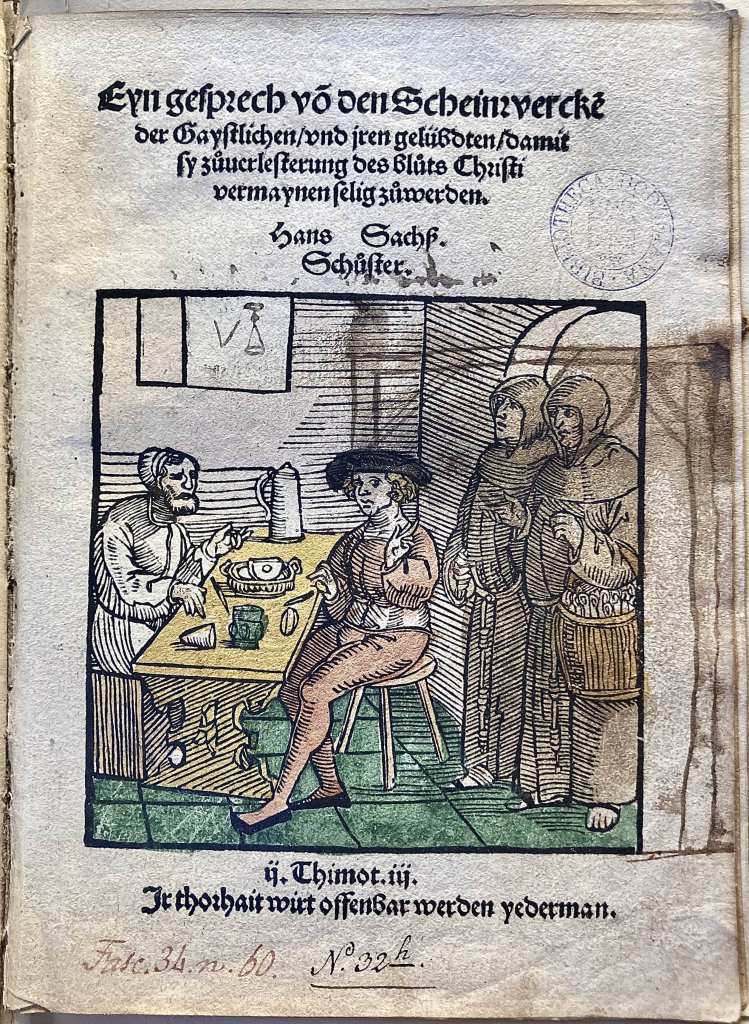

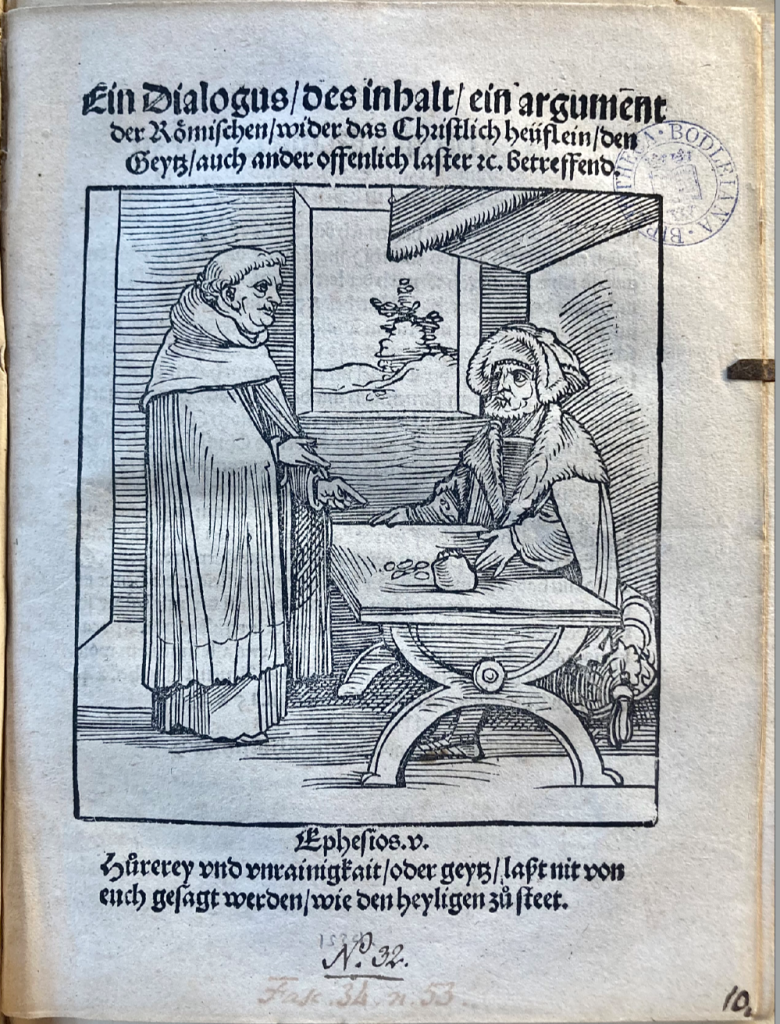

Two Franciscans dressed in religious habit enter from the right while Hans and Peter sit at a wooden table with food, drink and knives. The gestures of all four attest a lively discussion, the starting point of which is made visible by what the right monk is carrying in a large basket on his arm: They are collecting candles in order to perform their monastic duties of singing, chanting and reading.

In the Oxford copy Tr. Luth. 34 (60) of the pamphlet showing this woodcut, by Erhard Schön presumably,8 somebody has coloured in various parts using seven shades: yellow for the table, the monk’s basket and Hans’s or Peter’s hair, a reddish brown for his clothes, black for his hat, a sandy brown for the chair and bench, a dark green for the floor tiles and the beaker on the table, a dark brown for the monks’ tunics, and even a light beige wash shading in the flesh tones and the walls. Later, somebody, surely a different person, added drawings in brown ink: two shapes in the window (just doodles or a lamp?) and a large gallows standing outside the picture in the margin and reaching over the two monks, who have crudely been hung from it with two nooses round their necks.

This single page shows two distinct ways in which probable contemporaries of the Reformation engaged with the printed medium of the pamphlet. The colours are meant to increase the visual impact and the aesthetic value of the woodcut, which had proved an important selling point of prints and ideas alike. Especially illiterate audiences relied on pictures and the reading out aloud of published texts in public and private contexts. The reader who drew in ink on the page on the other hand treated the pamphlet as a cheap medium which did not have to remain pristine. His drastic imagery of having the Franciscans hung from the gallows likely shows an emotional response to Sachs’s critique of mendicant monastic life and the climate of the Reformation. Comparable examples from the time show how on the other side Catholic readers drew on reformers’ printed portraits delegitimising their sometimes saintlike appeal while also making fun at them by giving them ink moustaches.9

Who were the people whose engagement with Sachs’s dialogues, going as far as a symbolic execution, can still be observed today? The pamphlets in the Bodleian reveal more about them. Another of these pamphlets, Eyn gesprech eynes Euangelischen Christen mit einem Lutherischen shelved under Tr. Luth. 34 (58), shows glosses and drawings in ink on the first and last page as well as in the margins. These include doodles of a face in profile and, on the last page, first ‘Der’, then, after what looks like a reference marker, ‘lieb vber ale lieb hat bie | mir ein eren dieb’.10 (‘He who loves love above all has in me a thief of (his) honour’?)

These rhyming words read like a rebuke of the dialogue’s conciliatory ending, where Sachs cites the Epistle to the Philippians: ‘If there be therefore any consolation in Christ, if any comfort of love, if any fellowship of the Spirit, if any bowels and mercies, Fulfil ye my joy, that ye be likeminded, having the same love, being of one accord, of one mind’ (Phil 2:1–2) and so forth. Such a sentiment would not have resonated well with a radical anti-Catholic. For it seems the scribe was no other than the person who symbolically hanged the Franciscans and of whom a more and more coherent picture unfolds.

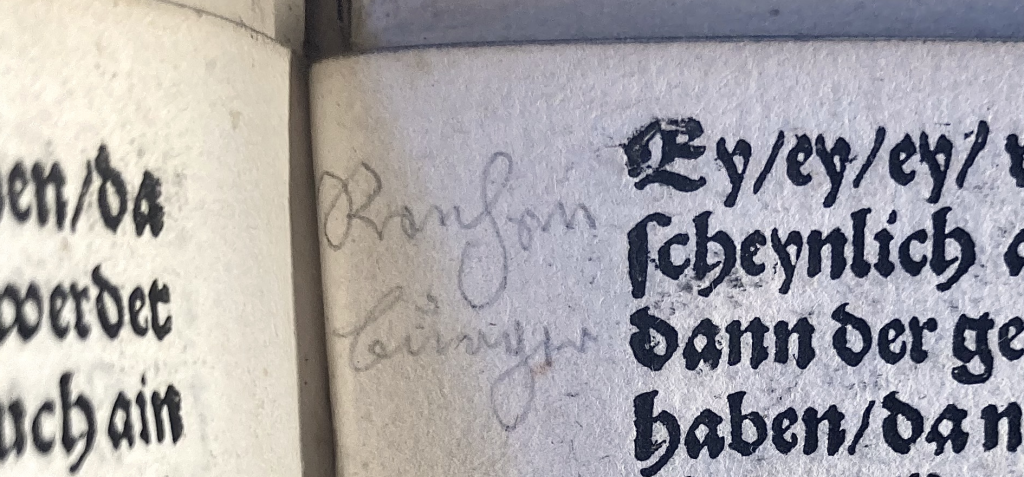

The writing is smudged, and the reason for that can be seen on the page with the drawn-in gallows. Just above the woodcut, beneath the name of the author ‘Hans Sachß. Schůster.’ (‘Hans Sachs. Shoemaker.’), there is the matching inkblot that resulted from the pages being pressed together when the ink was still wet. Judging by the script, the two pamphlets now numbered 60 and 58 must have been part of the same collection in the sixteenth century already, being bound together in a volume where 58 preceded 60.

Examining the Bodleian copies, one can add at least one more pamphlet to those two. It is the Disputation zwischen einem Chorherren vnd Schuchmacher, numbered 57 (Ill. 6). To facilitate finding the beginning of each item in a combined volume, leather tabs were permanently fixed to the last folio of the pamphlets, each about one centimetre lower down the page than the preceding one. Over time these left a slight indent on the opposing next page, which can still be seen even if the pamphlets are bound in a different order today. All three pamphlets show matching leather tabs on the last folio and indents on the first, so that they must have been bound together following each other – in an order that exactly fits the most likely chronology of publication:11 57 – 58 – 60. They come from a similar region and may have been bought there. Two were printed in Nuremberg, one in Bamberg, probably all first editions. The frontispiece of 57 is coloured in, and especially the dark green of the ground and the slippers seems similar to the tone used in 60. But the shading is more intricate, differentiating between darker and lighter areas in two different colours, which shows even more care in making the pamphlet a visually appealing object. Again, the reader who drew the gallows might not have been the first owner.

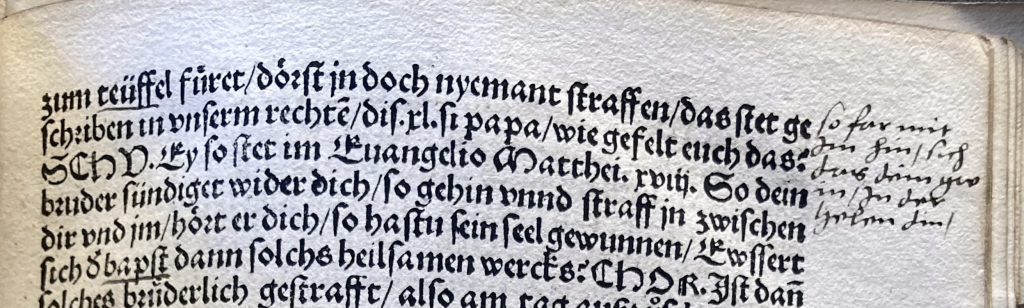

In all three pamphlets, single words and short phrases have been underlined in ink, and 57 and 58 further contain some glosses that comment on these words and phrases. They all seem to have been written by the same scribe, probably identical with the artist of the gallows. At the beginning of the first dialogue, the canon wants to send Sachs and Luther to hell (the shoemaker Sachs had written about Luther using the image of a nightingale): ‘Ey / der teüffel holl den schůster / mitsampt seiner Nachtigall’ (‘the devil take the cobbler together with his nightingale’, 57, fol. A2r). The reader of the pamphlet reacted by underlining the words they disagreed with and addressing the fictional canon in his gloss: ‘gmach o Herle das wirt ain seltzame nachtigal sain’ (‘Calmly, little man, that is going to be a special nightingale’). A little later, the canon insists that the pope cannot be punished for any crime: ‘Ey lieber / vnnd wenn der bapst so boͤß wer / das er vnzelich menschenn mit grossem hawffen zum teüffel fuͤret / doͤrft in doch nyemant straffen’ (‘My good man, even if the pope were so evil as to lead numerous people in a large crowd to the devil, still nobody would be allowed to punish him’, fol. A2v–A3r). Again, the reader turns directly to the canon, now evidently angry and in versified form: ‘so far mit jm hin / sieh das deine gwin / In der Helen din /’ (‘So go with him! See how your reward shall serve in hell’).

At the end of 57 (fol. C3r), the reader comments on the closing biblical verse in a way that seems very similar to the note on the last page of 58. The edition ends with Paul’s words ‘Ir Bauch jr got’ (‘Their belly, their God’) of Paul (Phil 3.19). As in 58, the reader makes use of a mark in the form of a virgule which might in both cases serve to connect the printed word with the handwritten note and continues with a rhyme: ‘die warheit schlecht sy zu tott | dan sy nur gottes spott’ (‘truth kills them as they are only a mockery to God’). The glosses of 57 and 58 show a reader who engages enthusiastically with the text, taking a strong anti-Catholic stance. In 57 they defend Sachs while in 58 they apparently disagree with his plea for patience and consolation.

Apart from 57, 58 and 60, there are five further German editions of Sachs’s Reformation dialogues in the Bodleian collection. They, too, preserve signs of their usage and history: the different sizes to which they were cut down earlier, painted edges, leather tabs and the impressions of leather tabs, finger prints, one more gloss, folio numbers as well as numbers and letters to count items. All of these show how typesetters, earlier readers and owners interacted with the pamphlets making them individual objects that tell personal stories about the usage of these printed materials from the Reformation in their time and after.

people operating the press

For example, in the pamphlet numbered 55 somebody wrote the name ‘Raichenburger’ in the inner margin. This reverses the placement of a printed or handwritten catchword which anticipates the first word of a new page at the foot of the preceding one to assist binding and reading: the gloss here repeats the end of the last line of the previous page (‘Reychenbur.’) at the beginning of the next one. The desired effect must have been to facilitate reading, probably out loud and perhaps even in different voices or with different performers, as the page break coincides with a change of speaker.

Different features speak of various collections in which many of the pamphlets were apparently combined and bound together at some point between their publication in 1524 and their integration into their current order at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Among these is the foliation, written in large, round numbers in the upper corners of print number 56. Their easily recognisable forms appear quite often in the pamphlets shelved under Tr. Luth. in the Bodleian Library, though in none of the other seven Sachs dialogues.12 The same is true for the green fore edge of 55. It can be seen on a number of pamphlets in the collection, which have all been trimmed to about 14.1 to 14.6cm width.13 On one of these, Tr. Luth. 31 (190), it is apparent that the trimming and colouring of the edges are later than some handwritten entries, which could be from the sixteenth century. So it might well be that the green fore edges and maybe some of the other signs of former collections tell us less about how the pamphlets were used by contemporaries of the Reformation and instead attest to their later history when they had already become objects of the past. At this time, they had become a matter of interest for collectors, historians and libraries.

Collectors, auctioneers and librarians

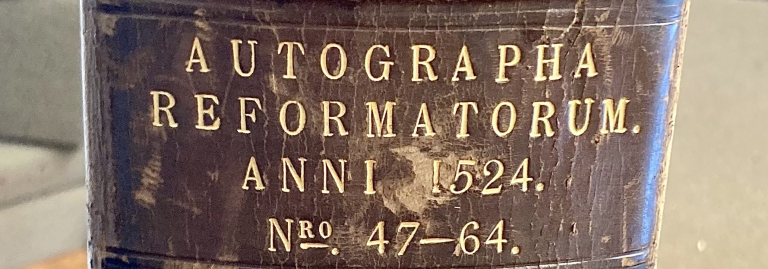

At the core of the Bodleian special collection called Tractatus Lutherani, which includes eight copies of Sachs’s Reformation dialogues, are84 volumes with c. 1,670 Latin and German tracts from the context of the German Reformation, all of them published between 1518 and 1550, and many of them pamphlets.14 They were collected by Johann Gottlob May (1754–1821), a schoolmaster and librarian from Augsburg.15 An advertisement from 1818, when May’s collection was sold at Sotheby’s in London, mentions that it was by this point already ‘chronologically arranged’,16 another that it was ‘carefully arranged in chronological order’.17 The Annals of the Bodleian Library record the acquisition of a ‘very valuable and curious series of original editions of Latin and German tracts, issued by the German reformers between 1518 and 1550’, already bound ‘in eighty-four volumes’.18 So it seems that May himself put them in the order they appear in today and had them bound in brown leather. He did not trim them but left them in their different shapes and sizes.

May had accumulated the pamphlets over a period of thirty years, incorporating in turn collections of the theologian Matthias Jacob Adam Steiner (1740–1796) and the historian Georg Wilhelm Zapf (1747–1810), both of them contemporaries of May in Augsburg.19 More is known about the work and collecting habits of these two than about those of May. Zapf published various studies on the Reformation and the history of book printing.20 Steiner collected everything from natural curiosities to engravings, coins, bibles and stained glass.21

It is not clear if any of the eight editions in question were part of Steiner’s or Zapf’s collections or where else they came from. The sales catalogues for their libraries, both probably co-written by May, do not list the pamphlets under their titles, but include entries like ‘[Ein Fascikel mit] 18 seltnen Originalschriften, die durch die Reformation Luthers zu Augsburg u. Nürnberg veranlaßt worden’ (‘a fascicle of 18 rare original publications prompted by the Lutheran Reformation in Augsburg and Nuremberg’),22 ‘12. Tractatus divers argument. et auctor. Deutsch’, published ‘1523–25’, ‘Gebunden’ (‘12 pamphlets of various subjects and authors in German, published 1523–25, bound’), and ‘50.’ plus another ‘48. Tractatus divers. argument. et auctor. in lingua lat. et. germ.’, published ‘1524’, ‘Ausgeschnitten’ (‘[98 (?)] pamphlets of various subjects and authors in German, published 1523–25, loose (?)’).23 It may well be that some of the eight Sachs pamphlets were among those but it is uncertain.24 In his handwritten catalogue of his own collection, which is kept in the Bodleian, May lists all eight pamphlets but does not indicate where or when he bought them.25

May’s catalogue of the Tractatus Lutherani mainly fulfils the function of an inventory. It designates two numbers to each item – apparently an older and a newer sorting system. Both numbers appear on the pamphlets as well. Apart from that, the focus of the catalogue lies on bibliographical information suitable for identifying the prints. May lists titles, author, the number of printed pages (‘S.’ for ‘Seiten’).

To this he adds the date and place of publication (for the eight pamphlets mostly ‘s. l.’ for sine loco or ‘s. l. et a.’ for sine loco et anno), the publisher (‘s. n. t.’ for sine nomine typographorum), the book format (‘4.’ for quarto). He gives exact information on the printed elements of the title pages including line breaks, mottos and woodcuts. What May’s catalogue widely ignores, are signs of usage and provenance – aspects regarding the prints as individual copies with a specific history different from other copies of the same print.

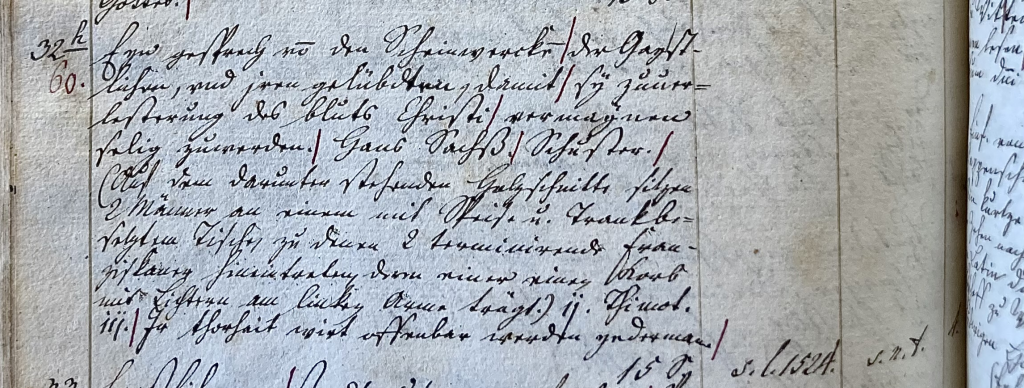

For example, following an exact transcription of the title on Tr. Luth. 34 (60) (Ill. 12), he describes its frontispiecein the following words: ‘Auf dem darunter stehenden Holzschnitte sitzen 2 Männer an einem mit Speise u. Trank besetzten Tische, zu denen 2 terminirende Franziskaner hineintreten deren einer einen Korb mit Lichtern im linken Arme trägt.’ (‘In the woodcut beneath there are two men sitting at a table set with food and drink. Two Franciscan monks enter collecting alms, one of whom is holding a basket with candles on his left arm.’) May does not make note of the fact that the woodcut has been coloured in, nor of the ink drawings and the ink blot on the title page or the leather tab secured to the last folio. In the case of Tr. Luth. 34 (57) he does note the coloured frontispiece but only to distinguish the print from the previous one: ‘Der nämliche Holzschnitt wie beym vorigen, aber illuminirt.’ (‘The same woodcut as in the previous one but illuminated.’)

In 1818, the Bodleian purchased May’s collection at Sotheby’s in London for 95 Pounds and 15 Shillings.26 The acquisition fell under the direction of Bulkeley Bandinel, who had been named Bodley’s Librarian in 1813 and remained in that position until 1860. Bandinel had more money at hand than his predecessors thanks to new library statutes approved in 1813 and to an increased deposit of new British publications following the Copyright Act of 1814.27 He used part of this money to buy libraries of private collectors all over Europe, acquiring amongst others printed books and manuscripts in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Sanskrit, Italian and German. ‘It was the scale of the acquisitions made when Bandinel was Bodley’s Librarian that marked his time in office as one of the greatest periods of expansion of the collections.’28

According to the Annals, the Tractatus Lutherani ‘probably comprise […] as complete a gathering of these controversial publications, so easily lost or destroyed from their small extent and often ephemeral character, as can anywhere be found.’29 In this evaluation the account takes its cue from a preface to May’s handwritten catalogue of the collection – a text which advertises its value and which, it has been presumed, might have been written by Samuel Sotheby himself.30 Sotheby, who, though a bibliophile, of course had a financial interest in the pamphlets, is known to have routinely hyped interest in his holdings.31 In the case of the Tractatus Lutherani this includes his repeated claim that among them are numerous autographs by Luther and other reformers.32 Sotheby also gives a reason why the pamphlets might be of academic value in a library in Britain:

It would be superfluous after these details, to say more of the interest and high value of this Collection for any public and private Library; – for every one, acquainted with literature, must be convinced, that without the aid of similar Collections, it is impossible to investigate the History of the Reformation on the Continent, which is so intimately connected with the History of the Reformation of this Country.33

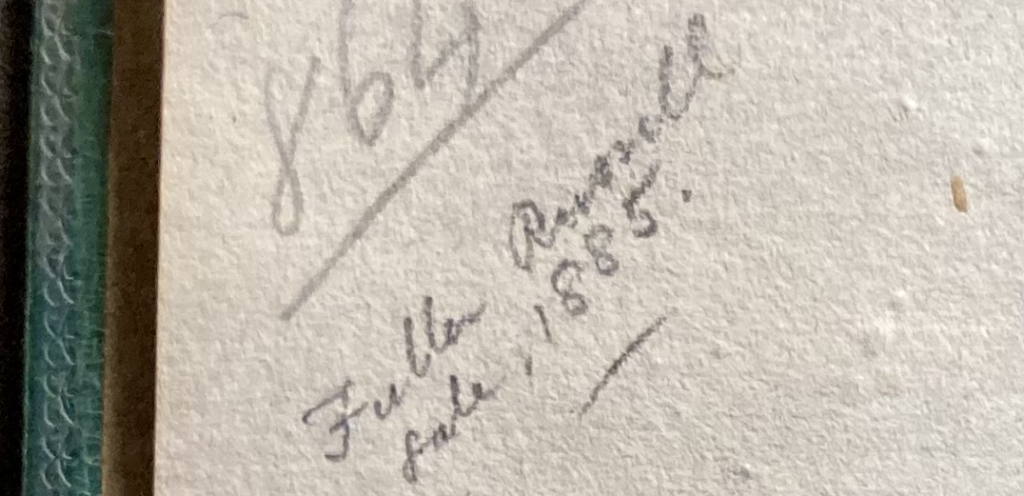

In addition to the eight German editions of Sachs’s Reformation dialogues, all published in 1524 and part of the Tractatus Lutherani, the Bodleian holds two copies of the English translation published by Anthony Scoloker in 1548. One of these, too, entered the collection in the time of Bandinel. It was part of the immense collection of prints, books, manuscripts and other items that was bequeathed to the library in 1834 by Francis Douce (1757–1834).34 Douce’s copy of A goodly dysputacion betwene a Christen Shomaker and a Popysshe Parson, however, preserves only the second part of the octavo volume, quires C & D.

For this reason, a complete second copy, printed in London like Douce’s, was purchased in 1885. It had belonged to Richard Heber (1773–1833), a bibliomaniac, who had a special interest in early English drama and whose immense collection of books and pamphlets, according to the Encyclopædia Britannica, ‘over-ran eight houses’.35 It was sold at Sotheby’s from 1834 to 1837. The London edition of A goodly dysputacion appears in the fifth volume of the 13-volume sales catalogue.36 Despite the rarity of the title, Heber owned two copies. A second one, an earlier edition printed in Ipswich, is listed in the second volume of the catalogue.37 The London copy was bought (or given to) the theologian and art collector John Fuller Russell (1814–1884), whose library was again sold at Sotheby’s. The 1885 sales catalogue mentions the rarity of the title: ‘Very scarce. The Author was probably the facetious Hans Sachs. This copy sold for £2. 3s. in Heber’s sale.’38 In the Bodleian copy of this catalogue can still be seen the annotations regarding the purchase.39 The first entry, ‘com. 53’, must mean that the library commissioned its agent to spend a maximum of 53 shillings (or £2. 13s.), the second, ‘got at 32’, that the winning bid was only 32 shillings (or £1. 12s.).

Besides the ten copies of Sachs’s Reformation dialogues in the Bodleian, an additional German copy from 1524 is kept by the Taylor Institution Library for Modern European languages which is the basis for our edition.40 Bound in a simple brown cardboard cover with marbled paper on the outside, it is an edition of the Disputacion zwischen ainem Chorherrenn vnnd Schüchmache. According to an inscription on the front flyleaf, it was once given as a birthday present: ‘Dem lieben Bruder Adolf zu seinem 65sten Geburtstage, den 7. Juli 1879.’ (‘To dear brother Adolf for his 65th birthday, July 7, 1879’). The copy was bought by the Taylorian in December 1924 for £5 – by far the most expensive purchase listed on that page in the register of additions – from the bookseller Gustav Fock in Leipzig.41 With this acquisition being the last, a total of eleven original copies of Sachs’s Reformation dialogues had been added to Oxford collections in the period from 1818 to 1925.42

The five-hundred-year history of the eleven copies involves diverse parties with varying interests, yet all (or almost all) strongly invested in Reformation pamphlets. The rapid succession of the four publications, quickly reprinted in a number of towns all within a single year, speaks of a fast-paced media landscape, which could swiftly react to current debates. Sachs made use of this as he wrote his four dialogues, focusing on different aspects, altering his stance and trying out literary strategies in a newly reinvented genre. The printing history is also a history of censorship and the difficulties and dangers of publishing in the time of the Reformation. How heated the debate was, can be seen most prominently in the emotional responses of one reader arguing with the text and its characters in the margins and symbolically hanging the two Franciscans in one of the frontispieces. Overall, the engagement of early readers shows how a pamphlet in the sixteenth century could be very different things: a valued object embellished with intricately coloured woodcuts, a functional text medium to be worked with, annotated and bound in miscellany volumes or even possibly a short-lived product of what must have seemed a mass production of affordable up-to-date prints that could be used for doodles. The copies that have survived still bear witness to their original multimedia contexts between text, image and performance, public and private, single pamphlet, miscellany volume and library.

Later, the collectors, bibliophiles, historians and auctioneers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries looked at them from different perspectives. The pamphlets had become historical objects, whose value could lie in their rarity and collectability, their use as historical sources or their alleged connection to famous men from the past. The acquisition for libraries, in Oxford from 1818 to 1925, marked them as matters of public research. This continues to this day, but the questions we ask them have changed, first with a growing interest in literary and sociological aspects of the texts and in recent years increasingly in material aspects of the individual copies. These can tell us more about the time of their publication, the people who interacted with them, the changing perspectives over the centuries and about the texts themselves.

List of the Sachs dialogues in Oxford

Tr. Luth. 34 (53)

Ein Dialogus / des inhalt / ein argumēt | der Roͤmischen / wider das Christlich heüflein / den | Geytz / auch ander offenlich laster ꝛc. betreffend. [Nuremberg: Jobst Gutknecht,]43 1524.

(Weller 1868: 18(a); KG, vol. 22: 9a; Pegg 1973: 3550; Köhler 1996: 3989; VD 16 S 211.)

Tr. Luth. 34 (54)

Ain Dialogus vnd Argument | der Romanisten / wider das Christlich heüflein / | den Geytz vnd ander offentlich laster betreffend ꝛc. [Augsburg: Philipp Ulhart, 1524.]

(Weller 1868: 18(d); KG, vol. 22: 9d; Pegg 1973: 3552; Köhler 1996: 3991; VD 16 S 210.)

Tr. Luth. 34 (55)

Ain Dialogus vnd Argument | der Romanisten / wider das Christlich heüflein / | den Geytz vnd ander offentlich laster betreffend ꝛc. [Augsburg: Philipp Ulhart, 1524.]

(Weller 1868: 18(c); KG, vol. 22: 9c; Pegg 1973: 3551; Köhler 1996: 3990; VD 16 S 209.)

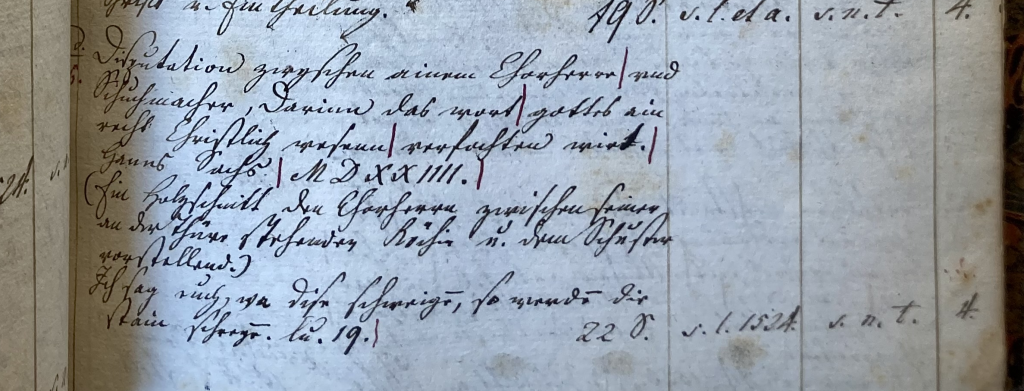

Tr. Luth. 34 (56)

Disputacion zwyschen ainem Chorherre | vnd Schůmacher / Darinn das wort | gottes ain recht Christlich wesenn | verfochten wirt. [Augsburg: Melchior Ramminger,] 1524.

(Weller 1868: 17(e); KG, vol. 22: 7e; Pegg 1973: 3553; Köhler 1996: 3994; VD 16 S 215.)

Tr. Luth. 34 (57)

Disputation zwischē einem Chorherren | vnd Schuchmacher darin̄ das wort | gottes vnnd ein recht Christlich | wesen verfochten würt. [Bamberg: Georg Erlinger,] 1524.

(Weller 1868: 17(a); KG, vol. 22: 7b; Pegg 1973: 3554; Köhler 1996: 3995; VD 16 S 220.)

Tr. Luth. 34 (58)

Eyn gesprech eynes Euangelischen | Christen / mit einem Lutherischen / darin | der Ergerlich wandel etlicher / die | sich Lutherisch nennen / ange|zaigt / vn̄ bruͤderlich ge|strafft wirt. [Nuremberg: Hieronymus Höltzel,] 1524.

(Weller 1868: 20(b); KG, vol. 22: 10c; Pegg 1973: 3558; Köhler 1996: 4001; VD 16 S 302.)

Tr. Luth. 34 (59)

Ain Gesprech aines Euangeli-|schen Christen / mit ainem Lutherischen | darinn der Ergerlich wandel etli-|cher / die sich Lutherisch nennē | angezaigt / vnd bruͤderlich | gestrafft wirdt. [Augsburg: Philipp Ulhart,] 1524.

(Weller 1868: 20(e); KG, vol. 22: 10g; Pegg 1973: 3560; Köhler 1996: 3999; VD 16 S 297.)

Tr. Luth. 34 (60)

Eyn gesprech vō den Scheinꝛverckē | der Gaystlichen / vnd jren gelübdten / damit | sy zůuerlesterung des blůts Christi | vermaynen selig zůwerden. [Nuremberg: Hieronymus Höltzel, 1524.]

(Weller 1868: 19(b); KG, vol. 22: 8c; Pegg 1973: 3562; Köhler 1996: 4006; VD 16 S 321.)

Footnotes

For full titles and full bibliography, see part 4 of the introduction

1 Kaufmann 2022, pp. 7–11.

2 Otten1993, pp. 102–108.

3 Rettelbach 2019, pp. 94–96; Schuster 2019, pp. 93–94.

4 According to the VD 16. Bamberg (Georg Erlinger): VD 16 S 219 (not listed in KG, vol. 22), S 220 (=KG, vol. 22, 7b), S 221 (=7a); Augsburg (Melchior Ramminger): S 215 (=7e), S 216 (=7c), S 217 (=7f), S 218 (=7h); Speyer (Jakob Schmidt): ZV 31754 (not listed in KG); Erfurt (Matthes Maler): ZV 13538 (not listed in KG); Eilenburg (Nikolaus Widemar): S 222 (=7d); Straßburg (Wolfgang Köpfel): S 223 (=7i); Vienna (Johann Singriener): S 213 (=7j), S 214 (not listed in KG).

5 VD 16, see also Schottenloher 1913, p. 236. In other older publications on Sachs, Nuremberg is sometimes named as one of the towns in which the poem was printed.

6 Cit. von Soden 1855, p. 162.

7 VD 16 S 224 (not listed in KG, vol. 22). The printer is unknown.

8 For this attribution see Schreyl 1976, no. 15.

9 Rößler 2018; Warnke 1984, pp. 67–68.

10 The words are smudged. Reading suggested by Ulrich Bubenheimer.

11 Proposed by Otten 1993, pp. 102–108; see also Otten 1994.

12 In the neighbouring volumes, the following pamphlets show this foliation: Tr. Luth. 36 (102) with the folio numbers 9–36, Tr. Luth. 35 (67) with numbers 95–102, Tr. Luth. 35 (80) with numbers 119–126, Tr. Luth. 36 (103) with numbers 127–159, Tr. Luth. 33 (56) with numbers 246–257 and Tr. Luth. 35 (85) with numbers 344–351. Perhaps, if one were to search more volumes, a complete reconstruction of this former collection could be achieved.

13 In the neighbouring volumes, the following pamphlets have this size and edges in the same shade of green: Tr. Luth. 31 (167), Tr. Luth. 31 (169), Tr. Luth. 31 (190), Tr. Luth 36 (90), Tr. Luth. 50 (9) and Tr. Luth. 50 (16).

14 Cf. Bodleian Library 2024; Attar 2016, p. 329; Jefcoate/Kelly/Kloth 2000, p. 297; Bloomfield/Potts 1997, p. 515.

15 The name variant ‘Johannes’, which most often appears in English publications, seems to be a misunderstanding of May’s Latinisation of his name as ‘Joannes Gottlob May’ on the two Latin title pages of his catalogue (May 1818, s. p., cf. also the same Latinisation under the Latin preface in May 1798, p. IV). I cannot find the name ‘Johannes’ anywhere in historical sources from May’s lifetime.

16 ‘Intelligence, Literary, Scientific, &c.’ 1818, p. 123.

17 ‘Literary Notice of Dr. May’s Collection’ 1818, p. 210. Both advertisements largely follow the wording of Samuel Sotheby, as can be seen in his preface to May’s catalogue of the collection. There it says: ‘The Collection is carefully arranged in chronological order’ (Sotheby? 1818, fol. 6v).

18 Macray 1890, p. 303.

19 ‘Having besides an opportunity of enriching his own Collection with a great part of those of Steiner and Zapf of Augsburg, he succeeded in getting together a more numerous and perfect assemblage of Tracts, illustrative to the early history of the Reformation than had ever been before made.’ (Sotheby(?) 1818, fol. 5v, cf. Jefcoate / Kelly / Kloth 2000, p. 297).

20 Cf. Schön 1898; Gradmann 1802, pp. 801–809.

21 Baader 1795, pp. 93–100, contains a detailed footnote on Steiner’s collections that comprises no less than eight pages, despite the book being written as a travel report.

22 May / Wilhelm 1797, p. 139. For Steiner’s library cf. also May 1798.

23 Beyschlag / May / Bürgle 1812, pp. 416 f. For Zapf’s library cf. also Zapf 1787 (in which I could not find mention of Reformation pamphlets).

24 It could also be that May did not want to put items on public sale which he preferred to buy for himself and hence did not list them in the sales catalogues.

25 May 1818, fol. 75r–75v. Warm thanks go to Alan Coates and Oliver House for their help locating the manuscript, which is now shelved under Library Records c. 1819 (formerly under R.6.212).

26 Cf. Macray 1890, p. 303.

27 Cf., also for his purchases, Clapinson 2020, pp. 138–142.

28 Ibid, p. 139.

29 Macray 1890, p. 303.

30 Jefcoate/Kelly/Kloth 2000, p. 297.

31 Cf. Micklich 2024 about a purchase for the Bodleian in 1835 of a manuscript falsely advertised to have probably been written by Melanchthon and Sotheby’s marketing strategy of ‘fabricating a Bibliotheca Melanchthonia’ (Georg Kloss).

32 Apart from Sotheby(?) 1818 cf. also the advertisements ‘Intelligence, Literary, Scientific, &c.’ 1818 and ‘Literary Notice of Dr. May’s Collection’ 1818.

33 Sotheby(?) 1818, fol. 6v.

34 For Douce’s bequest cf. Clapinson 2020, pp. 143–148.

35 Encyclopædia Britannica 1911, vol. 13, p. 167.

36 Bibliotheca Heberiana 1834, p. 65.

37 Bibliotheca Heberiana 1835, p. 94.

38 Catalogue Russell 1885, p. 34.

39 Shelved under 2591 d.1 Sotheby 1885 Jan–June. Many thanks go to Simon Phillips for his kind help in locating and making sense of the Bodleian copy of the sales catalogue.

40 The provenance research has been done by Christina Ostermann, who is currently working on the acquisition of Reformation holdings for the Taylorian. Thanks also go to Gareth Evans for his help looking into the collection.

41 Cf. Taylor Institution Library: Register of additions to the Library 1922–34, as well as Taylor Institution Library: Cashbook of the Finch Fund, s. p. According to the cashbook, £5 2s. were paid to Fock in January 1926 (£5 for Sachs, 2s. for an edition of Goethe’s Faust by Heinrich Düntzer).

42 For an overview of the eleven copies cf. also Hartmann 2015.

43 According to VD 16 online. Otherwise the printer is usually identified as Hieronymus Höltzel.

3 thoughts on “Hans Sachs Edition 3: The Pamphlets in Oxford”