By Henrike Lähnemann

This is part of a series of introductory posts for the updated edition and translation of Hans Sachs’s first Reformation Dialogue ‘Chorherr und Schuhmacher’ (‘Canon and Cobbler’) in German (1524), Dutch (1540s), and English (1540s), published as Volume 5 of the Treasures of the Taylorian. Series One: Reformation Pamphlets. Ebook of the publication.

- The Historical Context (Tom Wood)

- English Reformation Dialogues (Jacob Ridley)

- The Pamphlets in Oxford (Philip Flacke)

- The Edition including the Bibliography (Henrike Lähnemann)

Related Taylor Editions

- Hans Sachs: Disputation zwischen einem Chorherren und Schuhmacher (1524)

- Een schoon disputacie (the Dutch translation of the early 1540s, coming soon)

- A goodly dysputacion (the English translation of the 1540s)

- Hans Sachs’s other 1524 dialogues (coming soon)

Preface to the Edition

2024 marks the 500th anniversary of Hans Sachs publishing in quick succession four prose dialogues which became bestsellers, particularly the first one where he has his alter ego, Hans the cobbler, debate a pompous priest – and win the day, of course. That the Taylorian was aware of the significance of this publication is clear from the date of its purchasing the ‘Dialogue’ copy which stands at the centre of the edition: 1924. It is a fitting continuation of the series which started as project to prepare for the quincentenary of the publication of the 95 Theses in 1517. In 2017, we opened the Taylor Editions series with the ‘Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen’, Martin Luther’s spirited (and not always accurate) defence of the way he had translated the Bible, a text which had been on the syllabus for German students in Oxford since 1917.

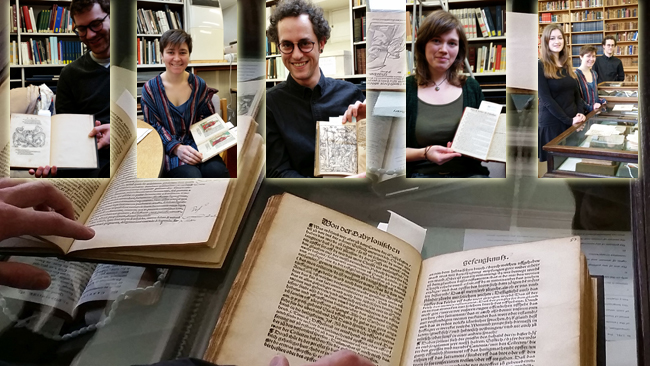

This has been a collective editing process over many years. Kezia Fender encoded the first version of the first dialogue in 2016 as a special option for her German and English combined BA course which was then continued by MSt. student Charlotte Hartmann as History of the Book project ‘Hans Sachs in Oxford’. The second-year students of ‘Paper VII’, a course on early modern German literature and culture, translated among them the first half of the first dialogue in February 2024, rising to the challenge of finding idiomatic equivalents to German proverbs and insults: Alexander Archer, Harrison Cartwright, Hannah Cowley, Lucy Gibbons, Elizabeth Gur, Ivan Halpenny, Leena Kharabanda, William Marriage, Olivia Rose, Oliver Schenke, Aaron Ung, and Eleanor Willcox. They were supported by David Hirsch, a translation studies student from Heidelberg on an internship during spring 2024.

Another intern, Philip Flacke from Göttingen, continued the work in the summer term and has since stepped up to be one of the editors of this volume, responsible for the book historical side. The project even led to him starting his doctoral project on concepts of truth in Hans Sachs’s texts. The bulk of the transcription work then was done by him and a number of other students, in the first place Timothy Powell who is also starting his doctorate on Hans Sachs, in this case on the reception history from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe to the GDR. Their work on the second and third dialogue, plus the transcription of the fourth dialogue by German BA finalist Nicholas Champness, have contributed to the commentary and book historical chapter in this volume and will be published as another book in the Reformation Pamphlets Series in January 2026, for the 450th anniversary of Sachs’s death. Two MSt. students, Montgomery Powell and Lucian Shepherd, jointly translated the second dialogue, and, together with MSt. students Viviane Arnold and Nina Unland provided the bulk of the biblical references (which, unsurprisingly given that Hans Sachs just had spent three years mainly studying the Bible and Luther’s writings based on it, make up a very high proportion of the dialogues, up to half of the actual text). Christina Ostermann, a History of the Book student of the first cohort, currently working on the history of the acquisition policy for Reformation pamphlets in the Taylorian, provided the transcription of the Dutch text and proofreading. Jacob Ridley not only annotated the early modern English but also provided the chapter on the English dialogues. We were fortunate to be able to win specialists and critical readers for different aspects, among them Andreas Wenzel and Daniel Lloyd for ecclesiastical terminology, Ulrich Bubenheimer for marginalia, and Howard Jones for linguistic advice. Numerous colleagues around Oxford joined in the discussion of translation conundrums such as how to translate the derogatory exclamation ‘py pu pa’ by the canon (see fol. a3v for the solution we settled on, suggested by Wes Williams).

Johanneke Sytsema helped locate a copy of the elusive Dutch edition which served as a relay station between the German and the English versions of the first dialogue. Margreet Vos and the curator of early printed works, Esther van Gelder, at the Royal Library in The Hague provided a microfilm copy and bibliographic information which then allowed Asmus Ivo, curator at the University Library in Greifswald, to find the missing pamphlet bound in a Sammelband. Alexandra Franklin, Richard Lawrence, and a group of colleagues at the Weston Library helped with the book historical chapter, and the Bodleian Library gave us access to the extensive run of Lutheran pamphlets and the unique copies of the English translation and granted permission for the liberal inclusion of images in this volume, with expert help from Alexandra Franklin and the other colleagues in the early modern department. As for the previous volumes, Emma Huber as the German subject librarian at the Taylor Institution and digital lead for the library provided expert help on the digital editions aspect and designed the cover.

Oxford, October 2024

Henrike Lähnemann for the editorial team

General Introduction

Hans Sachs (1494–1576), the Nuremberg shoemaker, prolific playwright, poet, and Meistersinger, has never completely vanished from the history of German literature. But more often than not, he has been first and foremost seen as a figure of cultural history, known beyond the German-speaking area as the main character in Richard Wagner’s opera ‘Die Meistersinger’. His poetry suffered from being considered a mechanical product, produced en masse, with near-comic effects of the rhyming couplets that count syllables rather than following natural speech. This was epitomised in the Baroque mock couplet

Hans Sachs war ein Schuh-/

macher und Poet dazu

(Hans Sachs was a shoe-/maker and poet, too).

The identification of his profession with his mode of writing was reenforced by Sachs’s practice to write himself into his texts; he signed his poems normally in the penultimate line, finding multiple rhymes for ‘Sachs’. In his first prose dialogue, he chose a different way of putting himself into the text: the main character is the cobbler Hans who has an inexhaustible stock of biblical quotations in German at hand – a reflection of the fact that the real Hans Sachs had spent the years 1520 to 1523 intensely studying the works of Martin Luther and his 1522 translation of the New Testament, not publishing anything himself in that period. But in 1523, he came back with a vengeance, and the result was the opposite of bland, monotonous, and mechanical. First, he wrote an allegorical praise of Luther as ‘the Wittenberg nightingale’ which became proverbial, and then a group of four sharp and witty prose dialogues, full of idiomatic phrases, proverbs, interjections, one-line put-downers, and asides, which must have been particularly entertaining for a local audience.

The form Hans Sachs used was one beloved by Humanists and their readers, the prose dialogue. A model which Sachs certainly knew was the early instalments of Erasmus’s ‘Colloquia familiaria’ (started in the late 1490s, first printed edition 1518), humorous and ironic encounters between characters taking opposing positions used as Latin exercises in schools. They allow a more informal tone and the integration of everyday characters, putting forward arguments more pointedly by dividing them up between the opponents.

Hans Sachs uses a number of different expressions for this form, The first dialogue uses the Latin academic term of ‘disputatio’ and describes it as a ‘fight’: Disputacion zwischen ainem Chorherrenn vnnd Schüchmacher darin das wort gottes vnd ein recht Cristlich wesen verfochtten wirtt. (‘Disputation between a canon and a shoemaker, in which there is a battle for the word of God and a truly Christian existence). The second and third are less confrontational between the protagonist, instead in a discursive style exchanging points of view and called a ‘conversatio’ (Gesprech eines evangelischen Christen mit einem Lutherischen) and (Gesprech von den Scheinwercken der Gaystlichen). The final one has two terms: ‘dialogus’ and ‘argumentum’ (Dialogus vnd Argument der Romanisten / wider das Christlich heüflein / den Geytz vnd ander offentlich laster betreffend).

This short, accessible format of live demonstrations of current religious topics were an immediate success, well beyond Nuremberg. Our introduction places this unique group of texts first in the historical context of Nuremberg, the first Imperial city which, only one year later, openly declared its alliance to Martin Luther – not least because of propagandists such as Hans Sachs. A comparative study of the Reformation publishing market in England in the 1540s, when the first dialogue was translated via Dutch into English forms the second part. The third part looks at the publishing history and then follows the way of the pamphlets into Oxford. A short practical guide on how to read the Early New High German texts closes the chapter.

Reading Early New High German

Early modern German was written to be performed. This is true for all Reformation pamphlets but particularly important to remember for Hans Sachs’s dialogues. Even though they were not written to be staged like his ‘Fastnachtspiele’ (bawdy Shrovetide plays), they use the same stylistic devices of frequent interjections, question and answer ping-pong, and insults. The audience would have had exposure to German verse and prose largely as listeners, whether through mystery plays, sermons, or public performance of the works of the ‘Meistersinger’. The best approach to these dialogues is therefore to read them aloud, in line also with the argument that Martin Luther put forward e.g. in the ‘Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen’ for the importance of idiomatic expression and the ‘street value’ of language.

This short introductory guide has been part of the whole series of the Reformation pamphlets but this is the first run of editions from Southern Germany with a distinctly different dialect by the author and – perhaps more importantly – the typesetters and printers, distinct from the East Central German of Leipzig / Erfurt / Wittenberg. All Sachs pamphlets discussed come from a cluster of towns within today’s Bavaria: The Imperial Free City of Nuremberg, the home of Hans Sachs where he lived all his life; Bamberg, the episcopal seat 60km north of Nuremberg, a Catholic stronghold but nevertheless less strict in enforcing publishing censorship than the ever-suspecting Nuremberg town council; they both belonged to the East Franconian area. Finally the flourishing trade centre Augsburg, 150km south of Nuremberg, where the reprint of the first edition of the first dialogue was produced which opens our edition, with an active print scene which picked up all new publications from best-selling authors such as Hans Sachs, which used mainly Swabian dialect conventions.

- Dialect

The edition shows a mix of East Franconian and Swabian features. Typical of East Franconian are the swapped plosives, voiced b, d, g used for unvoiced p, t, k, and vice versa, particularly at the beginning of words: ‘poden’ for NHG ‘Boden’; ‘driegerei’ for ‘Trügerei’. The other characteristic is a wide use of e-elision (apo- and syncope), resulting in many truncated forms such as ‘Cristn’ or ‘bericht’ for ‘berichtet’, while Central German tends to preserve the full forms with the final schwa-e. Typical of Nuremberg is the use of ‘e’ for ‘ö’ as in ‘Kechin’ for ‘Köchin’. - Punctuation

Early modern editions use full stops, brackets, question marks, and virgules as punctuation marks. The ‘/’ Virgel (virgule or forward slash) is the main means of structuring sentences, and can stand for both a comma and a semicolon. It is best to treat a virgule like a musical caesura, to pause for breath. Often the full stop at the end of a sentence is omitted, particularly if a capital letter follows. - Abbreviations

Typesetters took over from manuscripts some handy ways to save space. The main abbreviation mark is a bar (macron) over characters ‘-’. As a nasal bar above any letter, it replaces a following n such as ‘warē’ = waren or (mainly for Latin case endings) an m such as ‘Jtē’ = Item. The macron is also habitually used for ‘vn̄’ = und. Confusingly, the rounded z-form ‘ʒ’ stands both for z and for a number of established abbreviations, particularly in ‘dʒ’ / ‘wʒ’= das / was. In the transcription, ʒ has been rendered as z where it stands for the affricate sound /ts/ and has been resolved where it is used as abbreviation. Occasionally a hook is used for the -er ending, e.g. ‘ď’ = der; this has also been resolved in the transcription. - u/v/w – v/f – i/j/y, and different s– and r–forms

The Roman alphabet had only one symbol for u and v and one for i and j. u/v/w are interchangeable, as are i/j/y, and v/f are both used for f, e.g. ‘vnd’ = und; ‘zuuor’ = zuvor; ‘new’ = neu; ‘vleissig’ = fleißig; ‘jch’ = ich. In most cases, letters are pronounced as in the equivalent modern German word.

The two typographically different forms for s (long ſ versus round s) and for r (the round form of r = 2 being mainly used after characters with a rounded right-hand border such as o or – in some fonts – h) in the type set have not been distinguished in the transcription because they are simply graphic variations. Confusingly, the round r can also be used to stand for the more 7-shaped Tironian note ‘et’, used exclusively for ‘etc.’. This has been replaced with the ampersand ‘&’ which also started life as representing ‘et’ (the form is a ligature of an uncial ‘e’ and a lower-case ‘t’). - Umlauts

The umlaut sound would have been in the same position as in modern German, but there is no strict rule for writing it. In most cases, an umlaut should be used wherever one occurs in modern German. The Augsburg print workshop used superscript ‘e’ for ‘ö’ and long ‘ä’ as in ‘hoͤren’ and ‘vnzaͤlich’ (= ‘unzählich’), ‘ü’ for umlaut-u (probably to avoid confusion with ‘o’ above ‘u’ in words with old diphthong ‘uo’ such as ‘brůder’), ‘e’ for short ‘ä’. - Double versus single consonants and s/ß, k/ck, z/tz, r/rh, t/th

There is no consistency in writing single and double consonants such as f/ff or n/nn, nor is there a difference in pronunciation, i.e. ‘gottlich’ and ‘gotlich’ are pronounced the same. This also applies to s and ß (the latter started out as a ligature of long ſ and z to indicate a double consonant), to k and ck (the spelling for double k), and to z and tz. Note that z always sounds like modern German z, i.e. /ts/, not like English z. Again, almost all consonants can be pronounced like their modern German equivalents. - Use of h and e after vowels; long and short vowels

While in medieval German each letter would have been sounded, e.g. ‘lieb’ would have had a diphthong in the middle, ‘e’ after other vowels had become silent in the sixteenth century. This is evident from the use of e after i where there never was a diphthong, e.g. the word ‘diesen’. The same applies to h. In most instances a following e or h indicates a long preceding vowel, but this is not consistent, e.g. ‘jhm’ can stand both for modern im and ihm. Do not therefore pronounce h and e after vowels, but use long vowels as in modern German. - Word division and ‘Zusammenschreibung’

Hyphens in the form of ‘=‘ are used frequently but not consistently to indicate the continuation of words across line-breaks; if typesetters ran out of space in a line, they would assume that the reader would be able to link words without this visual prompt. Clear single words have been joined in the transcription but the irregular use of spaces between compounds has not been normalized. - Capital letters

Capital letters are used as in English to indicate the beginning of new sentences and for proper names but also for emphasis in words; these have not been normalized since they can be used for highlighting key terms. - Syncope, apocope, and contraction

Unstressed vowels are often absent where we should expect them in NHG; this is particularly pronounced in Upper German dialects, see above, either mid-word (syncope), e.g. ‘gsagt’, ‘gnug’, or at word-end (apocope). Such vowel loss can cause confusion, e.g. ‘gelob(e)t’, which looks like a present, may stand for the preterite ‘gelob(e)te’. Sometimes a consonant is lost along with a vowel, especially a repeated consonant, e.g. ‘laut’ for ‘lautet’, ‘veracht’ for ‘verachtet’, ‘verstorben’ for ‘verstorbenen’. Vowel loss also occurs by contraction between words, e.g. ‘ers’ for ‘er es’, ‘nympts’ for ‘nimmt es’, ‘zun’ for ‘zu den’. - Zero inflections and absence of ge- prefixes

Some neuter plurals have a zero-inflection in ENHG and look like singulars, e.g. ‘das/die werk’, ‘das/die wort’. Strong adjectives in the nominative and accusative singular could also be zero-inflected, e.g. ‘solch vnleidlich tyranney’. - Omission of auxiliaries and personal subject pronouns

The auxiliaries haben and sein are sometimes omitted, especially in subordinate clauses. Personal pronouns are also sometimes left out where they would appear in NHG.

Bibliography

The bibliography is a combination of full references for short titles used in the footnotes of the introduction and some general introductory books. This is obviously not exhaustive and is designed mainly for anglophone students of historical linguistics. Further resources are available at the Reformation editions website of the Taylorian https://editions.mml.ox.ac.uk/topics/reformation.shtml

1. Abbreviations

- DEEP – Database of Early English Playbooks. Open Access.

- DWb. – Deutsches Wörterbuch. https://woerterbuchnetz.de/?sigle=DWB. References ‘s.v.’ (sub voce) reference the lemma which is explained.

- Fnhd. Wb. – Frühneuhochdeutsches Wörterbuch. https://fwb-online.de/.

- KJV – The Holy Bible, Conteyning the Old Testament, and the New: Newly Translated out of the Originall tongues: & with the former Translations diligently compared and reuised, by his Maiesties speciall Comandement. London: Robert Barker 1611. Open Access Version on biblija.net.

- KG – Adalbert von Keller and Edmund Goetze: Hans Sachs. 26 vols., Tübingen: 1870–1908. Repr. Hildesheim: Olms 1964.

- L45 – Martin Luther: Biblia: das ist: Die gantze Heilige Schrifft: Deudsch Auffs new zugericht. D.Mart.Luth. Wittemberg: Hans Lufft 1545. Open Access Version on biblija.net.

- STC – A. W. Pollard and G. R. Redgrave (eds.) (1976–1991): A Short-Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland and Ireland, and of English Books Printed Abroad 1475–1640. Second edition, revised and enlarged, begun by W. A. Jackson and F. S. Ferguson, completed by K. F. Pantzer. London: The Bibliographical Society.

- VD 16 – Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachbereich erschienenen Drucke des 16. Jahrhunderts. Open Access (Full bibliographic reference for all Reformation pamphlets with linked-in digitized copies, continually updated; links: http://gateway-bayern.de/VD16+[letter]+[number]).

- WA – Martin Luther: Werke. Kritische Gesamtausgabe [Weimarer Ausgabe]. Weimar 1883 ff.

- VLC – Vulgata Clementina, 1592. Biblia Sacra juxta Vulgatam Clementinam. M. Tweedale (ed.). http://vulsearch.sourceforge.net/html, accessed via biblija.net – the Bible on the Internet. Biblical books are given with the abbreviations used for the Vulgate.

2. Editions

- Davidson, Clifford, Martin W. Walsh and Ton J. Broos (eds.) (2007): Everyman and its Dutch Original, Elckerlijc. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications.

- Hahn, Reinhard (ed.) (1986): Das handschriftliche Generalregister des Hans Sachs: Reprintausgabe nach dem Autograph 1560 des Stadtarchivs Zwickau von Hans Sachs. Köln et al.: Böhlau.

- Köhler, Reinhold (ed.) (1858): Vier Dialoge von Hans Sachs. Weimar: Böhlau. Open Access.

- Seufert, Gerald H. (ed.) (1974): Hans Sachs: Die Wittenbergisch Nachtigall: Spruchgedicht, vier Reformationsdialoge und das Meisterlied Das Walt got. Stuttgart: Reclam.

- Spriewald, Ingeborg (ed.) (1970): Die Prosadialoge von Hans Sachs. Leipzig: VEB Bibliographisches Institut.

3. Manuscripts

- [May, Johann Gottlob] (1818): [Catalogue of Tract. Luth.] (Catalogus autographorum Lutheri et coaevorum tam faventium ipsi, quam adversantium, aliorumque libellorum hisce temporibus scriptorum. [Partes 1 et 2.] Collegit ac descripsit secundum singulas lineas Joannes Gottlob May, D. D. Philosophiae ac archaeologiae Professor in Gymn. Annaeo. Aug. Vindel. 1810.). Oxford, Bodleian Library, Library Records c. 1819 (formerly under R.6.212).

- [Sotheby, Samuel (?)] (1818): ‘Some Account of Dr. May’s of Augsburg Collection of Tracts on the Reformation’. Bound together with May 1818. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Library Records c. 1819, fol. 3–6.

- Taylor Institution Library: Cashbook of the Finch Fund. Oxford, Taylor Institution Library, TL 2/5/2.

- Taylor Institution Library: Register of additions to the Library (accession registers) 1922–34. Oxford, Taylor Institution Library, TL 3/2/8.

4. Printed Sources

- Baader, Klement Alois (1795): Reisen durch verschiedene Gegenden Deutschlandes in Briefen, vol. 1. Augsburg: Johann Melchior Lotter. Open Access.

- [Beyschlag, Eberhard, Johann Gottlob May and Commerzienrath Bürgle] (ed.) (1812): Verzeichnis der ansehnlichen und auserlesenen Büchersammlung des verstorbenen Herrn Geheimen Rathes Georg Wilhelm Zapf, welche 1812 am 6. des Heumonats und folgende Tage in Augsburg Lit. F. Nro. 151 in dem Lorbe’schen Gute nächst dem Katzenstadel an die Meistbiethenden verkauft werden soll, Augsburg. Open Access.

- Bibliotheca Heberiana. Catalogue of the library of the late Richard Heber, Esq., part the second, removed from his houses in York-Street and at Pimlico, which will be sold by Auction by Messrs. Sotheby and son … (1834). London: Nicol. Open Access.

- Bibliotheca Heberiana. Catalogue of the library of the late Richard Heber, Esq., part the fifth, removed from his house at Pimlico, which will be sold by Mr Wheatley … (1835). London: Nicol. Open Access.

- Catalogue of the First Portion of the Extensive & Valuable Library of the Late Rev. John Fuller Russell, … which will be sold by auction by Messrs. Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge … (1885). London, J. Davy & Sons.

- Douce, Francis (1807): Illustrations of Shakspeare, and of Ancient Manners: With Dissertations on the Clowns and Fools of Shakespeare; on the Collection of Popular Tales Entitled Gesta Romanorum; and on the English Morris Dance, vol. 2.London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme. Open Access.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (1911), 11th ed. Wikisource edition.

- Gradmann, Johann Jacob (ed.) (1802): Das gelehrte Schwaben: oder Lexicon der jetzt lebenden schwäbischen Schriftsteller. Ravensburg: self-published. Open Access.

- ‘Intelligence, Literary, Scientific, &c.’, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, &c. Second series V, 26 (February 1, 1818), pp. 122–24. Open Access.

- ‘Literary Notice of Dr. May’s Collection of Reformation Tracts; (Autographa Lutheri et Reformatorum.)’, The Gentleman’s Magazine: and historical chronicle (March 1818), pp. 208–11.

- Macray, William Dunn (1890): Annals of the Bodleian Library Oxford with a Notice of the Earlier Library of the University. Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2nd ed. Open Access.

- [May, Johann Gottlob] (ed.) (1798): Catalogus Bibliorum quae collegit Matthias Jacobus Adamus Steinerus, b. m. pastor quondam eccles. evang. ad aedes St. Udalrici Augustae Vindel. et quae d. XXV. Novembr. MDCCIIC. aut omnia simul, aut singula plus licitantibus vendentur in aedibus Weilerianis. Augustae Vindel[icum]: Brinnhausser. Open Access.

- [May, Johann Gottlob and Gottlieb Thomas Wilhelm] (eds.) (1797): Verzeichnis der ansehnlichen und auserlesenen Bücher- und Kunstsamlung Weiland Herrn Matthias Jacob Adam Steiners, Pfarrers an der evang. Kirche zu St. Ulrich in Augsburg, welche den 16ten October 1797 zu Augsburg in Weilerischen (ehemals Maschenbauerischen) Hause nächst dem Weinstadel an die Meistbietenden verkauft werden soll. [Augsburg:] Brinhaußer. Open Access.

- Schön, Theodor: ‘Zapf, Georg Wilhelm’. Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 44 (1898), pp. 693 f. Open Access.

- Zapf, Georg Wilhelm (1787): Merkwürdigkeiten der Zapfischen Bibliothek. 2 vols. Augsburg: Christoph Friedrich Bürglen/self-published. Open Access here and here.

5. Secondary Literature

- Arnold, Martin (1990): Handwerker als theologische Schriftsteller: Studien zu Flugschriften der frühen Reformation (1523–1525). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Attar, Karen (ed.) (2016): Directory of Rare Books and Special Collections in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. London: Facet.

- Bagchi, David (2016): ‘Printing, Propaganda, and Public Opinion in the Age of Martin Luther’ in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: OUP. Open Access.

- Barton, Anne (1990), The Names of Comedy, Oxford: OUP.

- Beare, Mary (1958): ‘The later dialogues of Hans Sachs’, Modern Languages Review 53, pp. 197–210.

- Bernstein, Eckhard (1993): Hans Sachs: mit Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.

- Blayney, Peter W. M. (2013): The Stationers’ Company and the Printers of London, 1501–1557. Cambridge: CUP.

- Bloomfield, B. C. and Karen Potts (ed.) (1997): A Directory of Rare Books and Special Collections in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. London: Library Association, 2nd ed.

- Bodleian Library (2024): Rare Books. Named collections index. Last Updated September 2, 2024. Open Access.

- Clapinson, Mary (2020): A Brief History of the Bodleian Library. Oxford: Bodleian Library, rev. ed.

- Creasman, Allyson F. (2012): Censorship and Civic Order in Reformation Germany,1517–1648: ‘Printed Poison & Evil Talk’. London / New York: Routledge.

- Drummond, Andrew (2024): The Dreadful History and Judgement of God on Thomas Müntzer: The Life and Times of an Early German Revolutionary. London/New York: Verso.

- Freeman, Janet Ing (1990): ‘Anthony Scoloker, the “Just Reckoning” Printer’, and the Earliest Ipswich Printing’ Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society Vol. 9 No. 5, pp. 476-496.

- Füssel, Stephan (2019): Gutenberg, transl. by Peter Lewis London: Haus Publishing.

- Hartmann, Charlotte (2015–16): Hans Sachs in Oxford: Bodleian and Taylorian Library: Wittenberg Nightingale and Reformation Dialogues https://hanssachsinoxford.wordpress.com/.

- Heijting, Willem (1994): ‘Early Reformation Literature from the Printing Shop of Mattheus Crom and Steven Mierdmans’ Nederlands archif voor kerkgeschiedenis/Dutch Review of Church History Vol. 74, No. 2, pp.143-161.

- Holzberg, Niklas (2021): Hans Sachs. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Holzberg, Niklas and Horst Brunner (2020): Hans Sachs: Ein Handbuch. 2 vols. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter.

- Jefcoate, Graham, William A. Kelly and Karen Kloth with the Assistance of Holger Hanowell and Matthias Bauer (eds.) (2000): Handbuch deutscher historischer Buchbestände in Europa, vol. 10: A Guide to Collections of Books Printed in German-speaking Countries before 1901 (or in German elsewhere). Held by Libraries in Great Britain and Ireland. Hildesheim/Zürich/New York: Olms-Weidmann.

- Kaufmann, Thomas (2022): Die Druckmacher: Wie die Generation Luther die erste Medienrevolution entfesselte. München: C. H. Beck.

- Kelen, Sarah A. (1999): ‘Plowing the past: “Piers Protestant” and the authority of medieval literary history’, Yearbook of Langland Studies 13, pp. 101–36.

- King, John N. (1976): ‘Robert Crowley’s editions of Piers Plowman: A Tudor Apocalypse’, Modern Philology 73, pp. 342–52.

- ––––––––––– (1982): English Reformation Literature: The Tudor Origins of the Protestant Tradition. Princeton: PUP.

- ––––––––––– (1999): ‘The book-trade under Edward VI and Mary I’ in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, ed. by Lotte Hellinga and J. B. Trapp, vol. 3: 1400–1557. Cambridge: CUP, pp. 164–78.

- Köhler, Hans-Joachim (1996): Bibliographie der Flugschriften des 16. Jahrhunderts. Teil 1: Das frühe 16. Jahrhundert (1501–1530), vol. 3.Tübingen: Bibliotheca Academica.

- Krümpelmann, Maximilian: ‘The History of the Taylorian Copies’, in Jones / Lähnemann (2020), pp. xxxix–lxvi. Open access.

- Lähnemann, Henrike and Eva Schlotheuber (2024): The Life of Nuns. Love, Politics, and Religion in Medieval German Convents, transl. by Anne Simon, Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. Open Access.

- Micklich, Rahel (2024): ‘Whose hand? Unearthing an Unknown Manuscript in the Bodleian’ in History of the Book. Exploring the World of Books at Oxford, ed. by Henrike Lähnemann. Open Access.

- Otten, Franz (1993): mit hilff gottes zw tichten … go zw lob vnd zw aǔspreittǔng seines heilsamen wort: Untersuchungen zur Reformationsdichtung des Hans Sachs. Göppingen: Kümmerle Verlag.

- –––––––––– (1994): ‘Die Reformationsdialoge des Hans Sachs. Revidierte Chronologie und ihre Auswirkungen auf das “Bild” des Nürnberger Dichters der Reformation’ in Dieter Merzbacher et al.: 500 Jahre Hans Sachs: Handwerker, Dichter, Stadtbürger. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz,pp. 33–37.

- Page, Christopher (2015): The Guitar in Tudor England: A Social and Musical History of Musical Performance and Reception. Cambridge: CUP.

- Pegg, Michael A. (1973): A Catalogue of German Reformation Pamphlets (1516–1546) in Libraries of Great Britain and Ireland. Baden-Baden: Valentin Koerner.

- Pollard, Albert Frederick (1897): ‘Scoloker, Anthony (fl. 1548)’, in Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 51, ed. by Sidney Lee, pp. 4 f. Open Access.

- Ranisch, Salomon (1765): Historischkritische Lebensbeschreibung Hanns Sachsens ehemals berühmten Meistersängers zu Nürnberg. Altenburg: Richter. Open Access.

- Reske, Christoph (2015): Die Buchdrucker des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebiet. Auf der Grundlage des gleichnamigen Werkes von Josef Benzig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2nd ed.

- Rettelbach, Johannes (2019): Die nicht-dramatischen Dichtungen des Hans Sachs: Grundlagen, Texttypen, Interpretationen. Wiesbaden: Reichert.

- Rößler, Hole: ‘Das nicht mehr schöne Bildnis. Druckgraphische Porträts als Medien der Diffamierung in der Frühen Neuzeit’, Medienphantasie und Medienreflexion in der Frühen Neuzeit. Festschrift für Jörg Jochen Berns, ed. by Thomas Rahn and Hole Rößler. Wiesbaden 2018, pp. 79–113.

- Schreyl, Karl Heinz (1976): Die Welt des Hans Sachs: 400 Holzschnitte des 16. Jahrhunderts, ed. by the Stadtgeschichtliche Museen. Nürnberg: Hans Carl.

- Schuster, Susanne (2019): Dialogflugschriften der frühen Reformationszeit: Literarische Fortführung der Disputation und Resonanzräume reformatorischen Denkens. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Steele, Robert (1910): A Bibliography of Royal Proclamations of the Tudor and Stuart Sovereigns and of Others Published Under Authority 1485–1714, vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Open Access.

- Valkema Blouw, Paul (1992): ‘The Van Oldenborch and Vanden Merberghe pseudonyms or Why Frans Fraet had to die’, Quaerendo 22, pp. 165–81 and 245–72.

- Warner, Lawrence (2014): ‘Plowman traditions in late medieval and early modern writing’ in The Cambridge Companion to Piers Plowman, ed. by Andrew Cole and Andrew Galloway.Cambridge: CUP, pp. 198–213.

- Warnke, Martin (1984): Cranachs Luther: Entwürfe für ein Image. Frankfurt a. M.: Fischer.

- Weller, Emil (1868): Der Volksdichter Hans Sachs und seine Dichtungen: Eine Bibliographie.Nürnberg: Jacob Sichling. Open Access.

- Wiggins, Martin (2012): British Drama 1533–1642: A Catalogue, vol. 1. Oxford: OUP.

- Wortham, C. J. (1981): ‘Everyman and the Reformation’, Parergon 29, pp. 23–31.

- Zlatar, Antoinina Bevan (2011): Reformation Fictions:Polemical Protestant Dialogues in Elizabethan England. Oxford: OUP.

6. Taylor Editions: Reformation Pamphlets. Oxford: Taylor Institution Library. Treasures of the Taylorian, Series 1: Reformation Pamphlets

- Jones, Howard (ed.) (2017): Martin Luther: Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen. An Open Letter on Translation. (First edition of the text with a freer translation). Open Access.

- Jones, Howard, Martin Keßler, Henrike Lähnemann and Christina Ostermann (eds.) (2018): Martin Luther: Sermon von Ablass und Gnade, 95 Thesen. Sermon on Indulgences and Grace and the 95 Theses. Open Access.

- Jones, Howard and Henrike Lähnemann (eds.) (2020): Martin Luther: Von der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen. On Christian Freedom. Open Access.

- Wareham, Edmund, Ulrich Bubenheimer and Henrike Lähnemann (eds.) (2021): Martin Luther: Passional Christi und Antichristi. Passional of Christ and Antichrist. Open Access.

- Jones, Howard and Henrike Lähnemann (eds.) (2022): Martin Luther: Ein Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen und Fürbitte der Heiligen. An Open Letter on Translation and the Intercession of Saints. 2nd ed. Open Access.

- Gieseler, Florian, Henrike Lähnemann and Timothy Powell (eds.) (2023): Martin Luther: ‘Mönchkalb’ and ‘Ursache und Antwort’ Two Anti-Monastic Pamphlets from 1523. Open Access here and here.

7. Bible Quotations

Biblical books are quoted in the abbreviations established for the Vulgate. The list gives the Latin names of the books and the titles established by Martin Luther for his Bible translation.

OT (Old Testament / Altes Testament)

Gn (Genesis / Das erste buch Mose), Ex (Exodus / Das ander buch Mose), Lv (Leviticus / Das dritte buch Mose), Nm (Numeri / Numbers / Das vierde buch Mose), Dt (Deuteronomium / Deuteronomy / Das fuͤnffte buch Mose), Ios (Joshua / Josua),

Idc (Iudices / Judges / Der Richter), Rt (Ruth), 1–2 Sm (Samuel), 3–4 Rg (Regum / Kings / Der Koͤnig), 1–2 Par (Paralipomenon / Chronicles / Chronica), 1 Esr (Esra / Ezra), 2 Esr (Ezrae secundus / Nehemiah / Nehemia), Est (Hester / Esther),

Iob (Job / Hiob), Ps (Psalmi / Psalms / Psalter), Prv (Proverbiorum / Proverbs / Sprüche Salomonis), Ecl (Ecclesiastes / Prediger Salomonis), Ct (Canticum Canticorum / Song of Songs / Hohelied Salomonis),

Is (Isaiae / Isaiah / Jesaia), Ier (Jeremiah / Jeremia), Ez (Ezekiel / Hesekiel), Dn (Daniel), Os (Osee / Hosea), Ioel (Joel), Amos (Amos), Abd (Abdias / Obadiah / ObadJa), Ion (Jonah / Jona), Mi (Micha / Micah), Na (Nahum), Hab (Habakkuk / Habacuc), So (Sofoniae / Zephaniah /Zephanja), Agg (Aggei / Haggai), Za (Zechariah / Sacharja), Mal (Malachi / Maleachi), Idt (Judith), Sap (Sapientiae Salomonis / Book of Wisdom / Das Buch der Weisheit), Tb (Tobia / Tobit), Sir (Ecclesiasticus / Book of Sirach / Jesus Syrach), Bar (Baruch), 1–2 Mcc (Maccabeorum / Maccabees)

NT (New Testament / Newes Testament)

Mt (Mattheus / Matthew), Mc (Marcus / Mark), Lc (Lucas / Luke), Io (Johannis / John), Act (Actuum Apostolorum / Acts of the Apostles / Der Aposteln Geschicht),

Rm 1–2 (ad Romanos / Romans / an die Roͤmer), 1–2 Cor (ad Corinthios / Corinthians / an die Corinther), Gal (ad Galatas / Galatians / an die Galater), Eph (ad Ephesios / Ephesians / an die Epheser), Phil (ad Philippenses / Philippians / an die Philipper), Col 1-2 (ad Colossenses / Colossians / an die Colosser), Th (ad Thessalonicenses / Thessalonians / an die Thessalonicher), 1–2 Tim (ad Timotheum / Timothy / an Timotheum), Tit (ad Titum / Titus / an Titum), Phlm (ad Philemonem / an Philemon), 1–2 Pt (Petri / of Peter / S. Peters), 1–3 Io (Iohannis / of John / S. Johannis), Hbr (ad Hebraeos / Hebrews / an die Ebreer), Iac (Iacobi / of James / Jacobi), Iud (Iudae / of Jude / Jude),

Apc (Apocalypsis / Revelation / Offenbarung Johannis)

4 thoughts on “Hans Sachs in Oxford 4: The Edition”