By Matthew McConkey

As anyone who has grappled with Single Sign-on can attest, humanities researchers and IT are often uneasy bedfellows. It was this perceived <div>ide that the 2024 history of the book students confronted last Wednesday: just what hides behind the intimidating pseudonyms ‘XML’ and ‘TEI?’ Luckily, we had an expert guide in Emma Huber, subject librarian for German at the Taylorian, to demystify the process. I’ve retreated to more familiar ground, and come up with a <list> of metaphors to lead the technophobe through our close encounter with the digital.

1. XML is (sort of) a language.

More accurately, it’s a code. But like a language, it has its dialects – and when compared to ‘Extensible Markup Language,’ the dialect that Emma taught us sounds practically homely: ‘Text Encoding Initiative’ (or TEI to his friends) allows us to create digital editions of manuscripts and print books, linking our transcriptions to facsimile pages for full ease of use. The XML editor ‘oXygen’ was our scribal pen and printing press, simplifying the process a good deal and pointing out mistakes with a jagged red underline.

2. XML is a Russian doll.

One of XML’s little quirks is that it likes its elements to be nested, one inside the other. This can be a problem in texts where there is some ambiguity or overlap – a <title> inside a <p>aragraph element gets the red line treatment. Similarly, manuscripts with confusing layouts, lots of images, or wonky tables are hard to encode. Everything in a digital edition requires a choice – do you include those marginal notes in an illegible hand? How can you simplify the layout to make it more accessible to those with a screen reader? We have to bear in mind, after all, that while theory is all well and good…

3. XML is a tool.

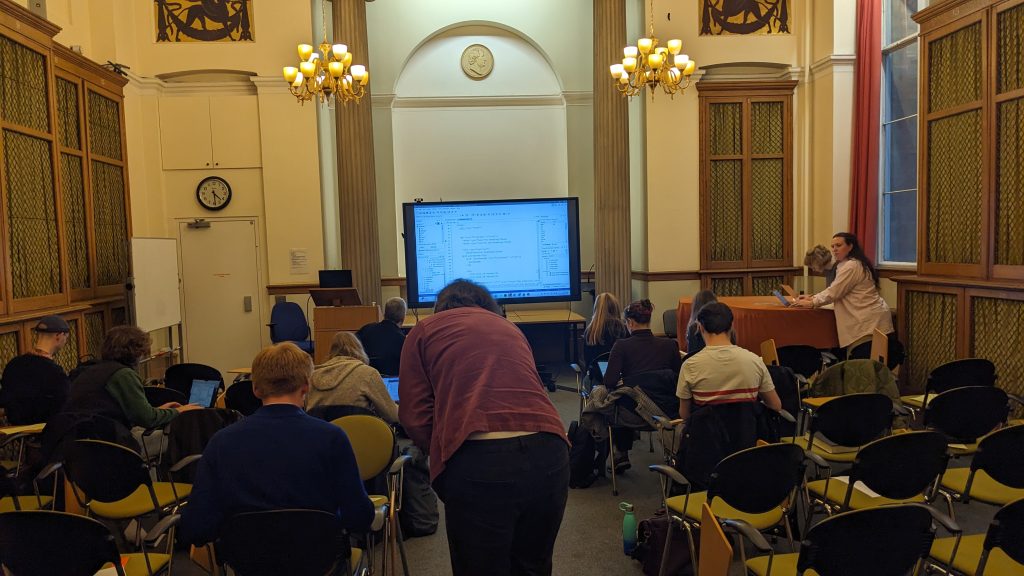

And it was with the practical aspects of TEI that we really got to grips in our session, firstly through a preliminary exercise, racing in groups to piece together a puzzle (see header image). And then hands on, each attempting to encode part of the books we had brought along. And though most of us didn’t get any further than the metadata, it was enough to sketch the edges of the potential of TEI.

4. XML is your best friend.

I left the session with a sense of the vast research applicability of TEI and digital editions. Properly tagged and catalogued, these editions are searchable for minute details, and, taken together, form databases that allow researchers to quickly access vital information. One example Emma showed us was the site CatCor, which collates a database of the letters of Catherine the Great, and allows us to create, for instance, a visual and chronological representation of her travels via an interactive map, or to search for the most common recipients across the metadata of more than 6000 letters.

Digital editions and TEI present a challenge to the traditional opposition of technology and the humanities. As the 2024-25 history of the book class continue to wrestle with them, they are also likely to present a (welcome) challenge to us!

Header image: the TEI puzzle or: <graphic> one of Shakespeare’s sonnets, in an unusual form… </graphic>