by Charlotte Ross

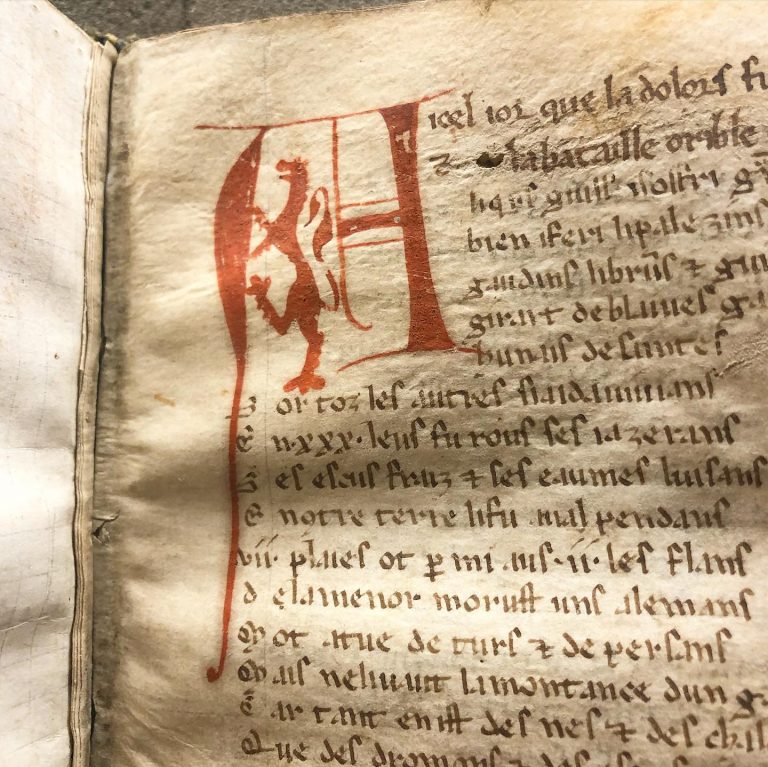

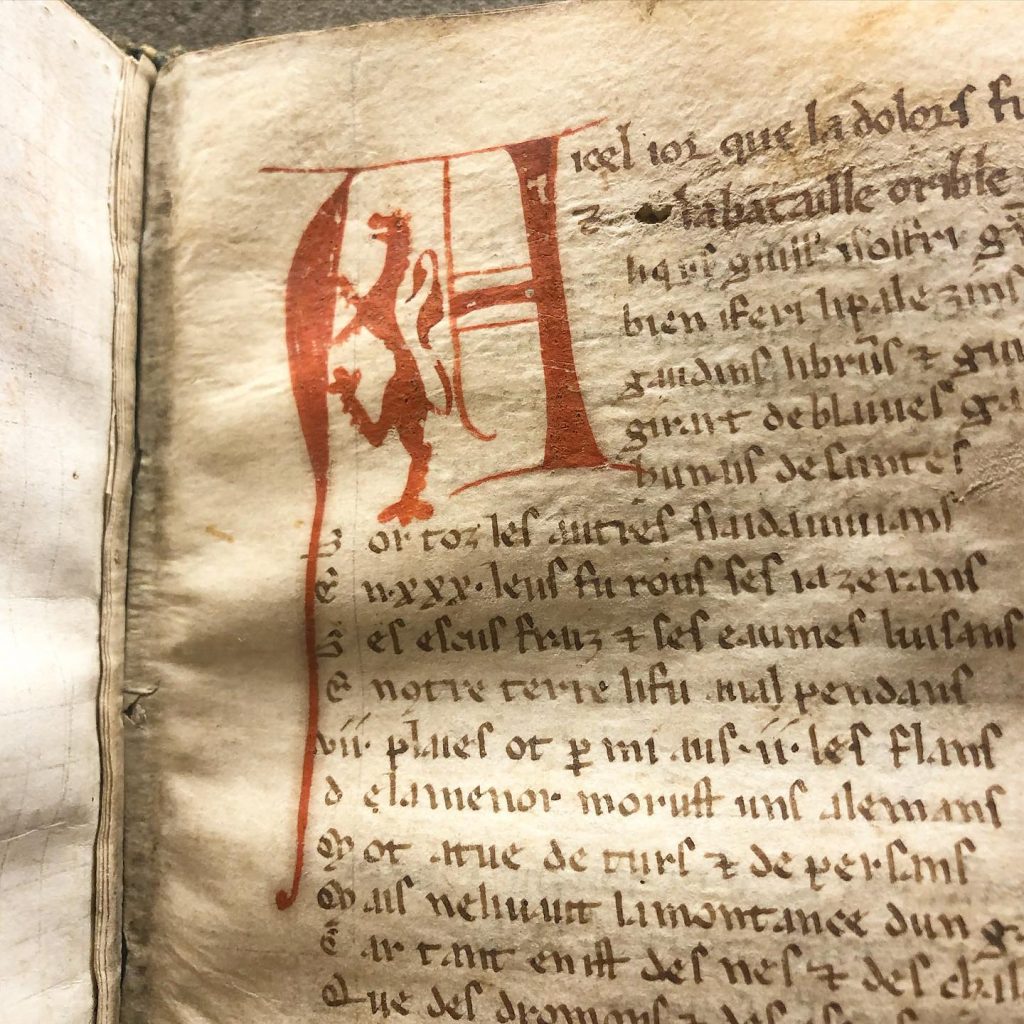

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Fr. e. 32 is a beautiful Old French manuscript that dates to the 12th century. Contained in this volume are the Chevalerie Vivien and an incomplete rendition of Aliscans, two poems from the Chanson de Geste tradition, which deals with French crusading narratives against the Moors and Saracens of Southern Europe.

My research concerns a particular character in the Aliscans narrative: a monstrous Saracen giant named Rainoart. In the poem, he is enslaved by a French lord and put to work in his kitchen, but is then taken under the wing of a crusading knight and educated in the ways of chivalry, eventually assimilating into society by converting to Christianity, becoming a lord and marrying.

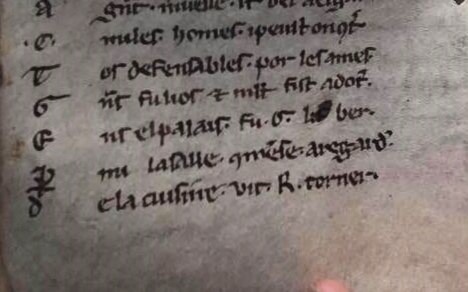

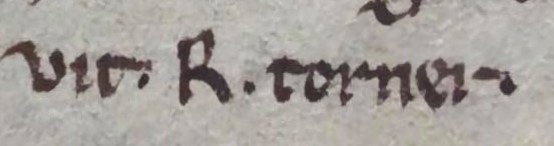

The reason I find this MS to be particularly interesting is its presentation of the characters’ names. In the moment when Rainoart is introduced to us, in his very first scene, his name is abbreviated to the letter R, rather than being spelt out in full. From this point on, his name is predominantly abbreviated to “R” or “Ren”, and only occasionally spelt out in full much later in the text. This was not something I was expecting to find when I opened the MS, as in every modern edition, this line is shown with his name spelt out in full. Yet perched on the last line of this leaf is this unexpected humble letter R.

This abbreviation in not unique to Rainoart; the names of other equally major characters are also abbreviated in the same style. Nor is it unique to the manuscript culture of the time: abbreviation is very common in medieval manuscripts, especially when naming characters. In this period, it is also prevalent in religious texts when referring to Saints or the names of months in calendars.

When a name is abbreviated, the text is making the assumption that the audience will be able to understand its meaning (within the context of the text) from a single letter. It signifies an established communal knowledge, an expectation of universal recognition. Therefore, in this MS, Rainoart’s abbreviated name implies that his character was sufficiently well known to be recognised from a single letter within the context of the manuscript. Considering the character’s earliest surviving appearance in written form is in a manuscript which barely pre-dates this MS, a mid-12th century manuscript of Chanson de Guillaume, this single, unassuming letter hints at the existence of a larger oral tradition which pre-dates these manuscripts. This would allow for an established knowledge foundation surrounding the text, making Rainoart recognisable to contemporary audiences.

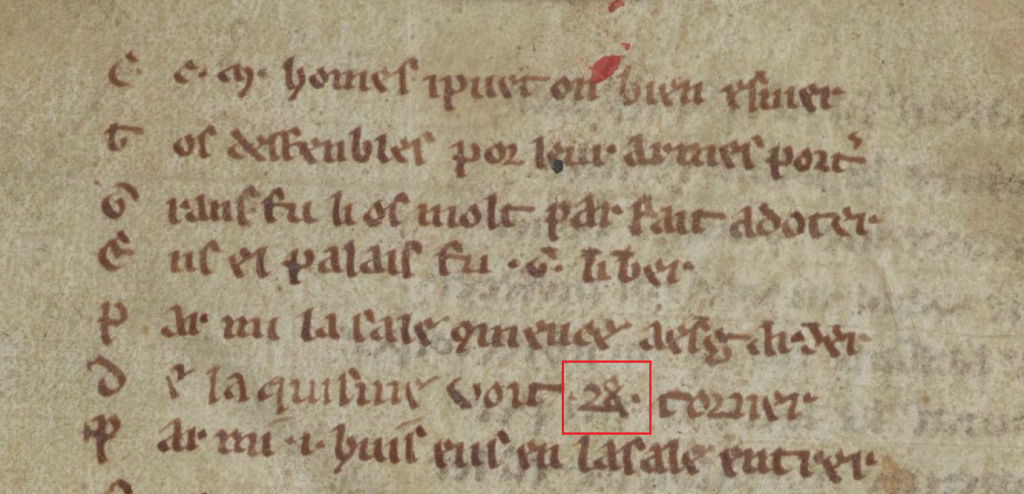

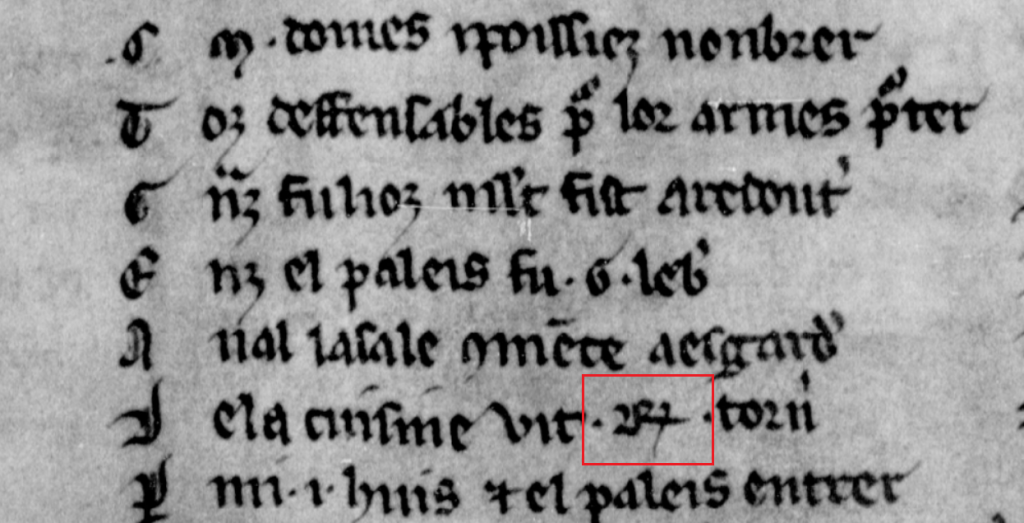

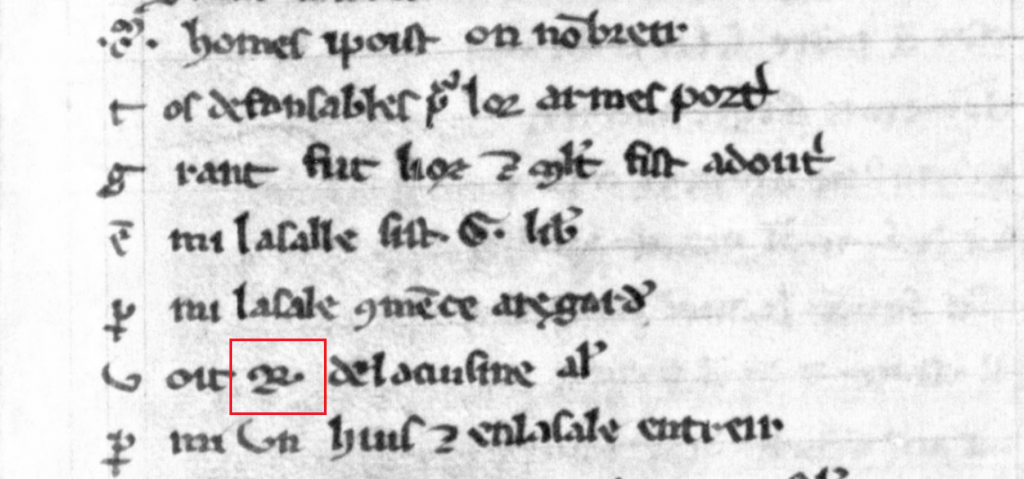

The same abbreviation is seen in three other manuscripts of this text. These images show the same line introducing the character in three 12th century manuscripts of Aliscans.

It is interesting to note that these abbreviated names do not appear in any modern printed edition of the text. Until the moment I opened this MS, I had believed that Rainoart’s name would be written in full throughout the text, as the editions had led me to believe. Having seen the MS, it has become clear that the editor did not consider the abbreviation to be relevant, as it is such a common trend in medieval manuscripts. However, whilst it does not offer any concrete conclusions on its own, I think this detail that hints at a pre-existing oral tradition enriches our understanding of both the text and its manuscript culture. It might just be a letter, but it is representative of a rich and cultured world of oral tradition which is now sadly lost to us.

Charlotte Ross is a first year MPhil student in medieval literature at the University of Oxford, and a member of St Cross College.