In the first week of the History of the Book methods option, students and researchers gathered in the Taylor Institute Library to explore items from the special collections that challenge the very notion of the ‘book’. From the curious collection of printed and handwritten manuscript pages rebound in Arch.Fol.It.1478(1) where Petrarch’s ‘sonetti et cançone’ are brought into touch with an Old English recipe, to the simplicity of the German Reformation pamphlets printed on a single folded sheet, e.g. ARCH.8o.G.1518 (5), approaching the form of the book made room for reflection on the nature of the ‘book’ itself. Focus on gems from the students’ own personal libraries enriched the discussion with consideration of the meaning of books beyond their printed form. Marginalia, provenance, elaborate sticky notes and – yes of course – flashy covers all played a part. Read more in detail below…

Ksenia Dugaeva – Too big, too small, just right… During the first History of the Book seminar, we were encouraged to think about the book as a material and cultural object, paying attention not only to the contents but primarily to the size, the binding, the illustrations and annotations found within. I was particularly enchanted by a pocket-sized edition of the collected works of Pierre de Ronsard (Arch.12o.F.1560 Pierre de Ronsard, Les œuvres de P. de Ronsard gentilhomme vandomois). The book was rebound in cardboard for conservation purposes, but the original parchment binding was conserved separately, too, with its curved edges overlapping the pages, seemingly designed to preserve them. The dainty annotations and the occasional stain on the pages made me think about the potential uses of this book, as well as the pedantry of its original readers. I thought further about the marks we leave on our editions of texts during the show and tell section of the seminar, learning about the peculiarities of the other participants’ marginalia, how personal and varied those annotations can be, notwithstanding the designation – or the size – of the book itself.

Cora Langnau – I really enjoyed the fact that we were encouraged to engage with the actual materiality and physicality of books using our haptic senses as well. Thanks to the brilliant idea of Charlotte, we added another sensory perception into the mix and turned the act of reading into an ASMR experience. We are still waiting for digital scent and taste technologies for an even more sensory experience of books online… Mini Qurans were used as and referred to as sancaks (banners), especially in the Ottoman tradition, because they were attached to military standards by sancakdars (standard bearers), who carried them into battles as talismans. What is interesting about miniature Qur’ans (and other miniature religious scriptures) is that they were and are literally produced and used as material objects in the first place, although they also could be and were read as sacred texts (while some only display key verses many contain the entire Qu’ranic text). So you would usually find them in gift shops not books shops, as I mentioned, or only displayed in particular libraries like the Lilly library the articles mentions as well. Interesting might also be the fact that in terms of the history of printing, due to their miniature format, which is more difficult to produce and reproduce in printing, they also had their own trajectory. Miniature scriptures had a long manuscript tradition and the Gutenberg printing “revolution” turned out to be not so revolutionary for them. At least as far as I know, there are miniature Qur’ans and other types of miniature scriptures & books printed from the 15th century onwards and printers experimented with smaller size formats, but they were more like pocketbook size, or even waistcoat pocket size. But since the traditional tiny miniature size of Qu’rans was not more than half a finger’s length and the letters barely visible to the unaided eye, they had to wait for their own microprinting revolution: Photolithography, which emerged in the 19th century.

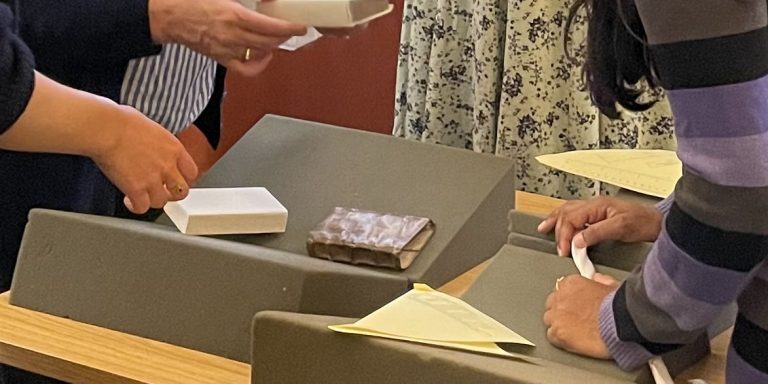

Charlotte Copeman – Only in Oxford, it seems, do you enter your first palaeography class of the year and find eight different rare incunabula laid out before you – indeed, not just laid out, but laid open. The sensory experience of these texts is multifaceted; with the materiality and sensory experience of reading these texts at the forefront of our interactions, Cora and I enjoyed searching for marginalia, illustration and decoration, and any indications left in the text as to their provenance or original printing date. The question of whether they are printed or handwritten prompted us to look for ligatures between individual letters (or here, the lack thereof), and feel for the indentations left by printing plates. Our discussion of what exactly constituted a book, however, was focused on the importance of binding – whether a ‘book’ was bound, how it was bound, and what role this played in its classification. When, for example, does a pamphlet stop being a pamphlet, and become a book? Before us we had a 1486 incunable rebound into a book for conservation purposes, but its original form is now unclear (Arch. Fol. G. 1486(2)). We were also provided with a brochure on the Reformation Pamphlets series printing this year, held together with staples. A pamphlet about a book about pamphlets… that may itself now be a book? The debate was engaging, the answer elusive.

Katarina Ristic – Attending a session, primarily intended as a sensory experience with books, via MS Teams makes for a unique experience. Fully conveying a book’s materiality through a screen seems difficult – not only when showing my own book, but also when viewing the books in the Taylorian. With the push for digitisation, more people may realise this – through virtually viewing books and manuscripts, rather than physically experiencing them. My book was a small, hardback translation of Ivan Turgenev’s ‘Fathers and Sons’, translated by C.J. Hogarth. It features a rounded back and gold font on the red cloth covering, with a centrally-placed debossed design on the front cover. It bears marks of previous ownership, with ‘Anne Hammond’ inscribed on the first page and a note indicating it was gifted to her in the 1960s. First published in this edition in 1921, this particular reprint is from 1948. J.M. Dent & Sons used The Temple Press in Letchworth, set up in 1905, to produce their ‘Everyman’s Library’ series of affordable, pocket-sized classics hardbacks, of which this book is #742. At the time of printing, the world was transitioning between mediums, yet this was still reprinted in hardback rather than paperback, which makes this book special to me.

Thomas Godfrey – Most university courses start with students asking each other the same old questions. Which college are you at? How’re you finding Oxford? What’s your specialism? In our first session of the History of the Book course, however, we got to know each other by presenting a book of our choice to the group. From seeing books that have sentimental value, to books that have been of paramount importance for a dissertation, this task allowed us to learn a lot about our peers and also to recognise the ways in which books are changed by their reader. I was struck by the immense amount of sticky notes and (charmingly illegible) scribbles that populated the two books that Charlotte and Kate presented to us. Such a process of annotation obviously changes the material nature of an object. However, we realised that a reader can also change a book through their emotional and historical relationship with it. The stories told about how each student came to possess their particular book made it clear that each book has a story that transcends the mere text contained within its bindings. As well as discussing our own books, the session allowed us to get familiar with the basics of handling rare materials and to share our initial thoughts about what constitutes a ‘book’. It was interesting that many of us thought that a book had to be of a certain length. This reminded me both of the Hugh Grant film ‘The Englishman who Went up a Hill but Came down a Mountain’, and of the debate surrounding whether or not Pluto is large enough to be considered a planet. I suppose it could turn into a rather heated discussion!

Kate McKee – What would Dante do if his BeReal notification popped up while in Hell? Maybe he would wait to post until he was doing something especially otherworldly, like riding atop a hairy beast with a scorpion tail and human head. Inspired by a woodcut illustration in the 1491 edition of La Commedia, commento di Cristophoro Landino (Arch. Fol. It. 1491), the Italianists of the History of the Book method option recreated the scene of Dante and Virgil riding atop Geryon in the seventeenth canto of Inferno. Using crowdsourced garments and props, Pietro donned Dante’s Florentine red and a laurel crown, and Tom wore Virgil’s classic blue. We constructed Geryon with a liberally-interpreted golden rope barrier, featuring Katarina (via Zoom) as Geryon’s human head. The format of BeReal—the social media app that prompts users, at a random point in the day, to take two photos simultaneously with the front and back lens of a phone camera—allowed us to showcase both our vision of the scene and the image from the woodcut with the book’s shelfmarks and our fingers for reference size.The exercise of creating a social media post featuring an incunable was an excellent exercise in seeing how we, as Book-Historians-in-training, can engage a popular audience with treasures of the Taylorian. I’m excited to see what’s in store next week!