By Kate McKee

A blog post from 2019 by a former History of the Book student documents the findings of Professor Cristina Dondi’s pioneering research on the material evidence in incunabula since the project’s inception in 2014. In this blog post, I focus on the 2021 illustrated copy census of an early printed edition of Dante’s work.

What does it take to document every extant copy of a specific edition of a book? Where do researchers begin such a daunting task?

As we learned in a presentation by Professor Cristina Dondi of Lincoln College, the task, also known as a copy census, does just that: researchers take stock of all the surviving copies of a particular edition through an epic feat of international collaboration between librarians, archivists, and scholars. In a copy census, librarians or researchers take account of each copy, noting data from the physical book itself. Handwritten notes, marginalia, and sale information—to name just a few data points—are then catalogued in a centralized database.

The excitement of conducting a copy census lies in how inconsistencies and consistencies from copy to copy of a particular edition can reveal a plethora of information. Data gathered from individual copies are crucial for the work of cultural and social historians, researchers interested in book ownership and provenance, and students of book history.

Dondi recounted one recent copy census completed by a global battalion of researchers in 2021. In recognition of the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death, the Cosortium of European Research Libraries organized and conducted an illustrated copy census of the 1481 printed book Comento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la Comedia di Danthe.

As an Italianist researching medieval literature, my ears perked up when Professor Dondi mentioned Dante’s Commedia. The Commedia, written at the beginning of the fourteenth century by the Florentine poet Dante Alighieri, tells the story of a particular Dante travelling through the afterlife. The three canticles (Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso) each include thirty-three canti, plus one introductory canto at the beginning of Inferno. With its complex imagery, theology, philosophy, and politics, the poem has remained an indispensable and genre-defying text for literary critics, historians, social scientists, mathematicians, and politicians since its initial circulation.

With the Commedia’s textual and visual richness, popularity, and influence in mind, it made for an exciting candidate for an illustrated copy census, and the 2021 census of the 1481 Comento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la Comedia di Danthe did indeed produce thought-provoking and surprising results. Provenance research demonstrated that these books initially fell into the hands of prominent, wealthy Florentine families, such as the Medici and the Cavalcanti. Dondi described the wide spectrum of conditions in the surveyed copies, including messy or incorrect illustrations, user illustrations in the margins, missing verses, personal notes, and heartfelt inscriptions.

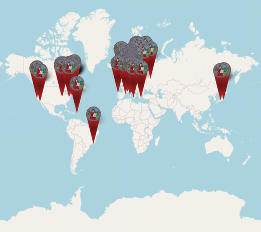

The comprehensive data set made possible a geographical visualization. Users can explore the results of the illustrated copy census and appreciate the global scope of the project using an interactive map with linked catalogue entries on the Material Evidence in Incunabula database. One copy of the Landino edition, for example, is held by Keble College in Oxford, and the database entry provides a description of the copy, its provenance, and catalogue entry. The entry also includes a link to the copy’s listing in the ISTC, or Incuncabula Short Title Catalogue, which tracks and lists 15th-century printed books. The seamless integration of these databases allows researchers around the world to quickly find copy-specific information from incunables in libraries near and far.

Besides the Dante illustrated copy census, Dondi’s larger project, 15cBOOKTRADE, aims to use incunabula as material evidence for historical study. In practice, the project tracks and traces the lives of books from their late-fifteenth century printing in Europe to their modern homes in libraries across the world. As Dondi reminded us, books are “dynamic” while libraries are “static,” meaning the potentially transnational stories of individual books can contrast significantly with the dormant nature of their current shelving.

The dynamism of books was on full display at the end of our seminar with the presentation of an incunable held by the Taylorian. A History of the Book seminar would not be complete without the investigation of a physical book, and this week we were treated to a 1472 letter collection by the Italian humanist Leonardo Bruni. We were captivated by the material evidence trapped between the covers: handwriting, pasted information, and crossed out writing integrated with print pages led us to imagine the many hands that held and interacted with the book in front of us. As we can learn from data accessible on MEI, the book was printed in Venice and then shuffled through many owners at varying price points, traveling between Venice, Siena, London, and Northamptonshire before settling at the Taylorian in Oxford.

The itineracy of the Bruni copy is only the tip of the iceberg in terms of its material history, and thorough data collection and cataloguing can make its particularities accessible to researchers around the world. As Professor Dondi reminded us, good data is fundamental to good visualizations, and the efforts of data collectors bring material evidence to life for a wide audience.