The Taylor Institution’s collection of Georges de Peyrebrune’s Works, a unique collection in the UK.

by Marie Martine, DPhil in Modern Languages (German and French)

I came across Georges de Peyrebrune during the first year of my DPhil as I was looking for women writers in contact with naturalist literary circles in end-of-nineteenth-century France. I became fascinated with Peyrebrune, born in the Périgord, who became very successful in Paris in the 1880s and 1890s with her political and feminist novels. She became one of the rare women published in La Revue des Deux Mondes and prestigious publishers. Despite her literary success, Georges de Peyrebrune struggled all her life with money and died in poverty, in 1917. Because of Peyrebrune having been forgotten and erased from the French literary canon, her works are particularly difficult to access. The Taylor Institution’s collection of her works is therefore unique in the United Kingdom as it holds several first editions of Peyrebrune’s works, as well as a wide range of digitalized ones. I organised this exhibition to make Oxford students and staff aware of this exceptional collection, but also to encourage them to (re)discover this captivating figure of the French Belle Epoque.

Georges de Peyrebrune’s trajectory tells us about what it means to be a woman and a writer in nineteenth-century France, which is no easy feat. Writers like George Sand and Madame de Staël, among others, have certainly paved the way for the next generation of women wanting to make a career out of writing; but men still reproach women to be too fragile and sentimental. Additionally, writing is seen as a distraction from women’s one and only duty: motherhood. Despite those ideological obstacles, women of the time used different strategies to access the literary market and it all had to do with names: they either wrote under a male pseudonym, used their husbands’ or fathers’ names, wrote under initials, or even anonymously. Peyrebrune chose the unisex name of ‘Georges’ (with an S!) that is of course derived from her birth name, Georgina, but which we can see as a tribute to many other writers who chose the name George as well (George Sand or George Eliot), inscribing Peyrebrune in a continuity within women’s writing history. A masculine name, on a cover or at the end of a journal article was thus a strategy for women of letters to make their way into the closed literary world. However, the Decadent writer, Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, claimed that he could ‘smell’ a woman writer from a book, because the feminine smell always betrays itself, even if the author used a male pseudonym. This approximative ‘science’ is very telling of how fin-de-siècle men made a parallel between the physicality of books with women’s bodies; not matter which masks women were using, they could always be discovered by men inhabiting the intellectual and spiritual sphere. Barbey d’Aurevilly used the qualifier ‘bas-bleu’ to negatively designate women with literary ambitions, a name derived directly from the English ‘blue stockings’. For him and numerous of his contemporaries, women are physically incapable to write books comparable to those by men and are to be labelled as ‘hysterical’. This sexist discourse reveals male anxieties in fin-de-siècle France more than it tells us about the true quality of women’s writing: not only did men worry about women getting out of their dedicated sphere, the household and motherhood, but they also worried about women writers becoming serious competitors on the literary market.

Georges de Peyrebrune is aware of those discourses, but she proudly reappropriates the term ‘bas-bleu’ to designate herself and her peers. She directly responds to those male anxieties in her play Jupiter et les Bas-bleu from 1894, which you will see displayed in the exhibition. In this comic play, she stages Emile Zola, one of the main literary figures of the time, under the traits of Jupiter, posing as a judge putting her contemporaries on trial. Well-known women writers defend themselves in front of this ruthless judge who rejects women’s ability to write on principle. The text ends with his definitive judgement: ‘elles n’enteront jamais à l’Académie !’. This is unfortunately true: the French Academy will only admit women as their members in 1980. Ironically, Zola himself will never get admitted either! What is interesting with this recently republished text is that Georges de Peyrebrune smartly mocks the anxieties of men writers fearing the competition from women. She debunks their pseudo-scientific arguments to justify women’s exclusion from public life and shows that the women of her generation have proven their ability to write. However, it is also worth noting that Georges de Peyrebrune herself was awarded the prize of the Académie Française twice in her life, once in 1896 for Vers l’amour and another time in 1899 for Au pied du mât. This institutional recognition shows that she was read and appreciated by her contemporaries. Even if many best-sellers of any period have been forgotten and might not be interesting for us as contemporary readers, it is important to recognize that the erasure of women writers from our canon is a complex phenomenon and cannot be justified by saying that women’s writing was less qualitative and interesting than their male contemporaries’.

Peyrebrune’s career also gives us a glimpse of feminine and feminist literary networks of the Belle Epoque. Peyrebrune’s correspondence shows that she stood in solidarity with other women writers and tried to build a literary network made of women. We unfortunately have few archives left from Georges de Peyrebrune, but some letters she received enable us to see how her contemporaries considered her as a generous mentor figure. For instance, in a letter from September 1912, Julia Daudet (the wife of the well-known writer Alphonse Daudet) asks Peyrebrune to support the publication of another woman writer. She writes: ‘Pourquoi favoriser toujours le travail masculin qui a toutes les chances, toutes les facilités ? […] Enfin je m’adresse à vous dont l’œuvre est toute généreuse et remarquable à tant de titres, dans un élan de justice féminine ou féministe, si vous aimez mieux’ (Why always favour men’s work which has all the chances, all the opportunities? […] I address you whose work is so generous and remarkable in so many ways, in a spirit of feminine or feminist justice, if you prefer). Daudet reflects on the numerous opportunities given to men to get their works published and publicized, compared to the few women get. Her conscious choice of the word ‘feminist’ is very telling: Peyrebrune’s ambition to have the value of women’s writing recognized is a feminist project. Daudet’s letter also demonstrates her confidence in Peyrebrune’s influence, highlighting that we are dealing with a respected and influential player in the literary market. Other letters from Georges de Peyrebrune’s correspondence show her as ready to help young writers by sharing her contacts within the publishing world and by giving her advice. One could think that in a society so hostile to women’s writing, the few who dared to publish would jealously protect their secrets, but Peyrebrune was clearly a woman who valued other talents and strived to help other writers.

This work towards promoting women’s writing led Georges de Peyrebrune to be part of the first jury of the Prix de la Vie Heureuse. In 1904, several feminist and women intellectuals were tired to see that the prestigious Prix Goncourt was again given to a man despite the talent of a potential female candidate Myriam Harry with her novel La Conquête de Jérusalem. They thus decided to build their own literary prize to finally recognize and reward women’s talents, as well as encourage contacts among women writers. Among Georges de Peyrebrune, we find in the jury Anna de Noailles, Julia Daudet, Daniel Lesueur, Marcelle Tinayre, Gabrielle Réval, Séverine and Lucie Delarue-Maldrus, all brilliant and influential writers of the time and well-established on the Parisian literary scene. This prize will become the Femina prize in 1917 and is still awarded today.

Peyrebrune’s friendship with her contemporary, Rachilde, is also fascinating. Both women had opposite worldviews and ways to respond to literary trends of their time, but their literary ambitions brought them together. Both come from the Périgord and tried their luck as writers in Paris. At first, Peyrebrune appears as a mentor for the young Rachilde who tries to navigate the capital city and its literary circles. As she marries Alfred Valette, director of the influential journal Le Mercure de France, Rachilde gains more influence. It was now Peyrebrune’s turn to ask for Rachilde’s support through her literary critiques to publicize Peyrebrune’s new publications.

Rachilde is known for being ‘the queen of the Decadents’ in fin-de-siècle France. She scandalized French audiences with her bold portraits of independent and sadistic heroines in her novels Monsieur Vénus (1889) and La Marquise de Sade (1887). Interestingly, she claimed loud and clear that she was not a feminist and often refused to be associated with other women writers, instead calling herself ‘homme de lettres’ (man of letters). Her pamphlet Pourquoi je ne suis pas féministe (1908) illustrates her anti-feminist stance. Peyrebrune, on the contrary, clearly revendicated to be a feminist, but her female characters can seem rather tame compared to the ones of Rachilde. Rachilde published several critiques of Georges de Peyrebrune’s novels in the Mercure de France and underlined her moralising tone. Georges de Peyrebrune makes Rachilde appear under fictional traits in the novel Une Décadente (The Decadent Woman, the only novel by Peyrebrune which has been translated into English) in which she criticizes the morbid values of the Decadents. A friendship between the two can thus seem quite surprising, but their letters show that they shared worries and advice on how to navigate the Parisian literary circles, making for a true literary friendship.

Finally, Peyrebrune’s concern with sexual violence in her fiction makes her works strikingly relevant for readers today. In a letter from June 1886, addressed to Georges de Peyrebrune, Rachilde mentions the way sexual harassment is a banal occurrence for young women writers: ‘En bonne franchise, quand une femme de lettres n’est pas une catin il faut au moins qu’elle puisse avoir l’air de l’être et au fond vous ne pouvez pas trop me donner tort, vous qui connaissez notre siècle’ (To be perfectly frank, when a woman of letters is not a whore, she at least needs to look like one and you cannot really disagree with me, you know our century all too well). Georges de Peyrebrune deals with this issue in Le Roman d’un bas-bleu (The novel of a Blue-Stockings, 1892) which tells the destiny of a young writer who falls into despair as she refuses to compromise her self-worth for literary success. This novel poignantly reflects the debates started by the #MeToo movement which unveiled the harassment and abuse faced by women, particularly in their professional lives. Already in the nineteenth century, Georges de Peyrebrune denounced this harassment and how it kept women from accessing the public sphere as equals to men. Her message strongly resonates with contemporary debates.

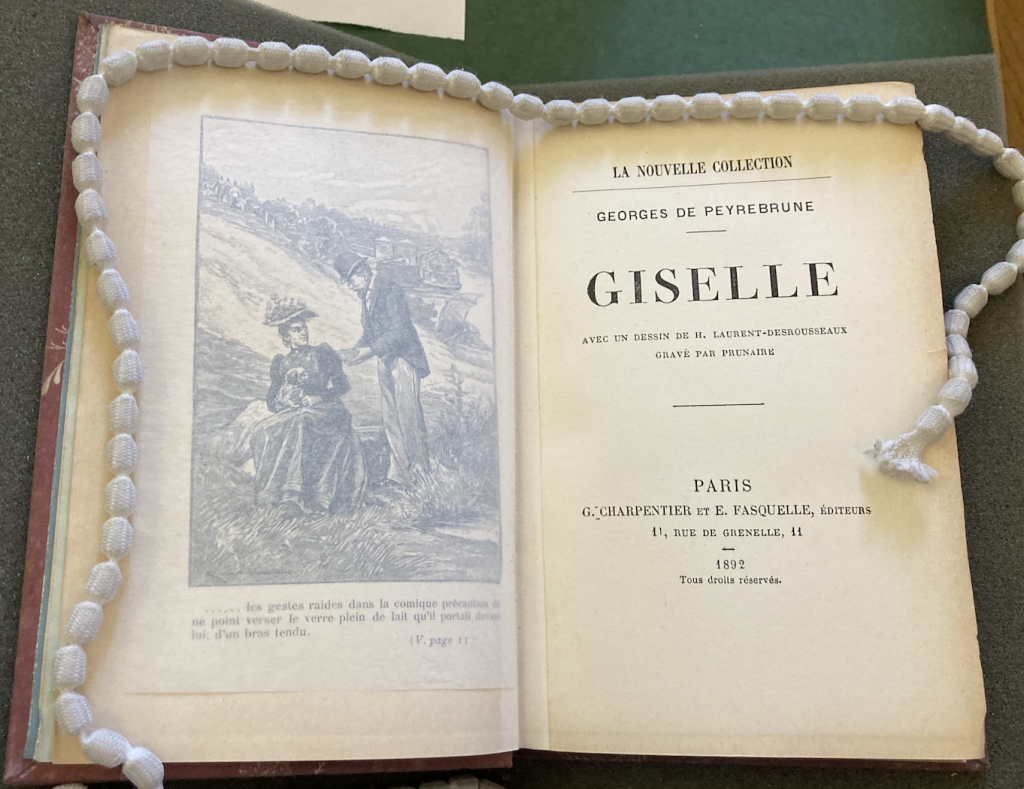

Peyrebrune’s literary career reflects the strategies French women writers were using to enter the literary market at the end of the nineteenth century, but also the obstacles and sexism they faced while doing so. Peyrebrune is an example of feminist solidarity, by promoting women’s writing and sharing her advice on navigating the publishing world. The Taylor Institution has now collected three exceptional copies of her works dating from her lifetime (an edition of Au Pied du Mât, a signed edition of Gatienne and an illustrated edition of Giselle) as well as some of her works that have been republished (Victoire la Rouge, Jupiter et les Bas-bleu, and A Decadent woman), making for a unique collection of Peyrebrune in the UK. More information on the Taylorian holdings in this blogpost.