One of the Taylor Editions practicum placement students from the MSc in Digital Scholarship programme writes on creating a digital edition of her own Slovak language learning notebook. Visit Kafka’s Languages in the Voltaire Room, Taylor Institution Library from 29 May–13 June to see the exhibition that inspired this project.

For the 2022–23 academic year, I moved to Slovakia to be an English teaching assistant at a vocational secondary school. I had a TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) certification and experience as a writing tutor, but I knew that most of my success as a teacher was going to depend on my ability to learn on the job. This included learning Slovak.

Before moving to the country, it was difficult to do any language learning preparation. At my secondary school and university, I had the option to choose from a combined 14 different language classes—more than most peers at other schools in my country had—but Russian was the only Slavic language option available. There are a handful of free Slovak self-study resources I found online, but teaching myself a language that has very little grammatical similarity with English proved to be a significant challenge. Duolingo offers Czech but not Slovak. While Wikipedia makes the claim that Czech and Slovak are mutually intelligible (and this sentiment was echoed by many of my Slovak friends and colleagues last year), Duolingo Czech didn’t seem like the right option for me. Basic phrases like “What is your name?” and the formal “Goodbye” don’t resemble each other at all in either language (or at least from an English speaker’s perspective).

About halfway through my teaching experience, I was able to get a place in a beginner Zoom Slovak language class organised by the country’s International Office of Migration. This class used a handful of existing language learning resources, like the Krížom-krážom textbook produced by Comenius University Bratislava, as well as materials produced by the lecturer himself. I meticulously followed along in an A5 notebook.

This Trinity term, conversations at the Taylorian seem to be geared toward language learning even more than usual because of the ‘Kafka’s Languages’ exhibition at the end of term. Knowing that I would be completing a practicum placement with Taylor Editions at the same time as this exhibition, I thought it would be a good opportunity to see what I could learn about my language learning process by creating a TEI/XML digital edition of my old Slovak notebook.

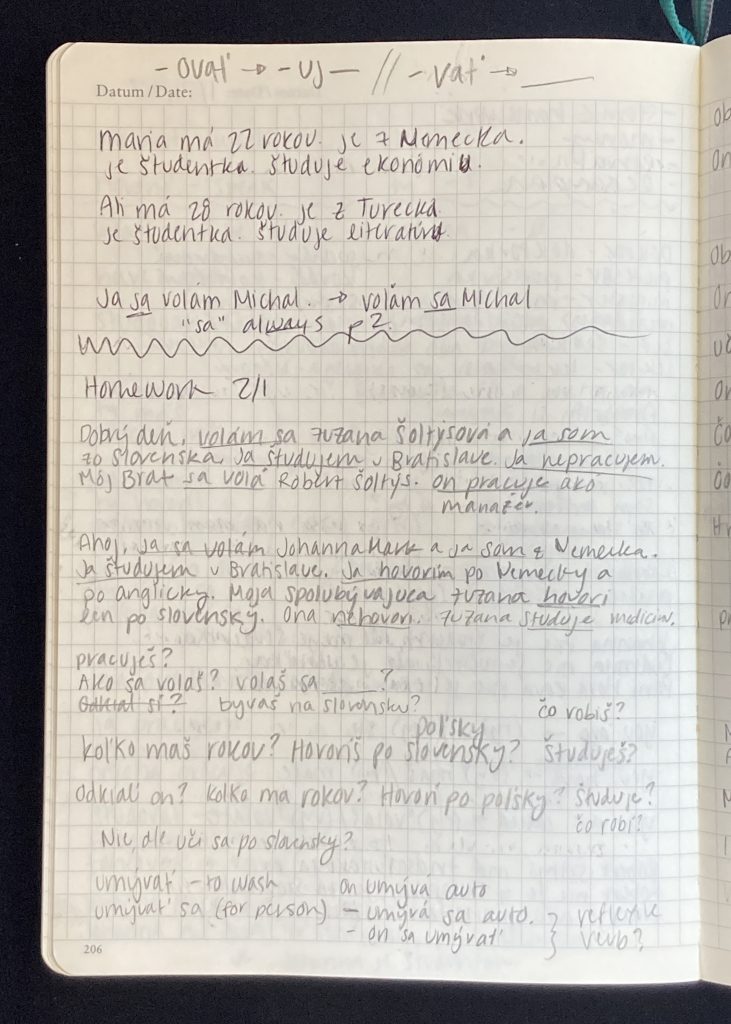

Having primarily worked with nineteenth-century printed documents in the past, this project gave me the chance to try encoding manuscript material for the first time. Because of this, I hoped to create a diplomatic digital edition. I picked a 4-page spread from early in the Slovak section of my notebook that included a variety of notes, sentences, and word lists to try representing a few different text structures in TEI/XML. Working with my own text, I could intuit divisions and structures that seem difficult to parse when working with unfamiliar manuscript material, and I have the added benefit of knowing my own handwriting. Font colours were encoded to reflect writing in blue and black ink and pencil, and lines between sections were recorded. These different features, along with the few cases where I recorded dates, helped to distinguish between textual divisions, which are marked with the <div> element.

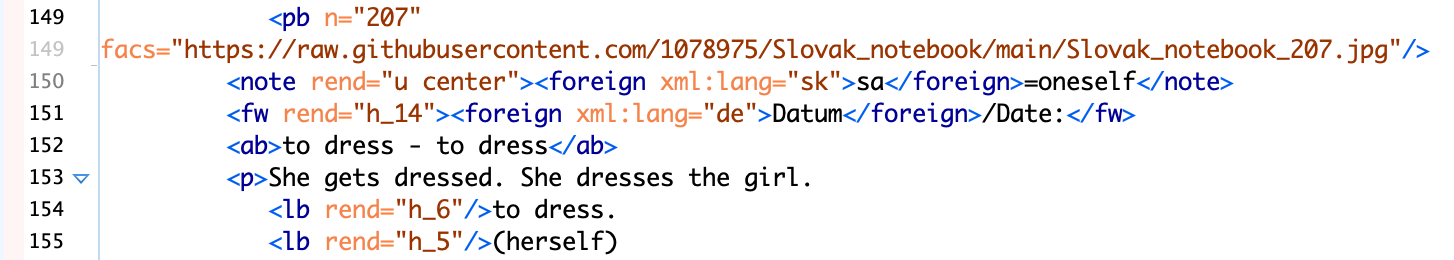

In cases where I was writing or copying complete sentences that aligned with the left margin, I used the straightforward paragraph element, <p>. Some pieces of writing were single-line Slovak to English definitions or essential grammar notes that also aligned to the left margin. As these were not complete sentences, the paragraph element was inappropriate, but because they were a core piece of the writing, the note element couldn’t accurately communicate the function of those pieces of text. In these cases, I used the anonymous block, or <ab>, element which serves “as a container for phrase or inter level elements analogous to, but without the same constraints as, a paragraph”. I used the <note> element to describe pieces of writing that were not complete sentences and either annotated another piece of writing or contained a general reminder. Another factor that helped me differentiate between using <note> as opposed to <ab> was the location on the page—notes are scattered across the page rather than aligning to the left margin.

In different sections of the text, I listed a word or sentence in English or Slovak, and then in a following column, wrote a translation and provided further examples. Because of the clear row and column format, I use the <table> element to describe these pieces of text. I use the <list> element twice—once to structure a word list and another to record a numbered true/false answer key. For the word list, I considered following the TEI guidelines for encoding dictionaries, but because this is meant to be a documentary edition and isn’t a practical language-learning resource, I decided to use the simpler <list> structure. This is also more compatible with screen readers than dictionary encoding.

I set the overall document language to Slovak using the @xml:lang attribute and the three-letter ISO language code “slo”, consistent with Taylor Editions best practice. Text written in English was overridden using the @xml:lang attribute with the ISO code “eng” on the <foreign> element, or whatever structural element was applicable. Because of the focus on languages for this project, I also recorded the forme work on the page, as the printed dateline includes the German “Datum”, which is marked with @xml:lang=”ger”.

While I was transcribing and encoding, I was surprised by the amount of Slovak I could mentally translate. Of course, this is elementary writing and most words that were unfamiliar when encoding were also unfamiliar to me when I was learning the language. Because of that, I had definitions written on many pages that I could refer to. When working on both the Slovak transcription and encoding and the encoded English translation of my notebook, I was reminded of some of the differences between Slovak and English that I struggled with as a student, which I tried to reflect in both TEI/XML documents.

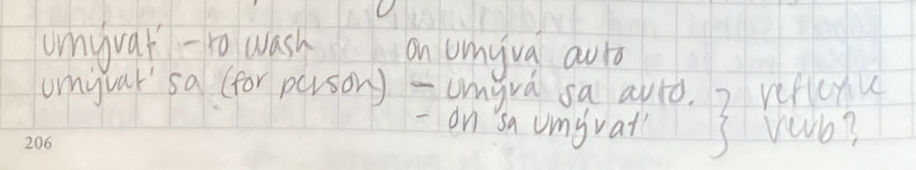

At this point in my Slovak learning, I was being introduced to the reflexive pronoun “sa” which is not easily translatable into English. The lecturer of my class was interested in helping us use the language more than he wanted to teach us the theory of Slovak grammar. When practising using verbs that take “sa” in my notebook, I made the connection that “sa” is paired with reflexive verbs, though I was not confident in this conclusion, as denoted by the question mark. I remember drawing this conclusion based on my experience learning about reflexive verbs when studying German, rather than my lecturer pointing this out. Later in my notebook, I made a note of the rough translation “sa = oneself”, though I don’t recall whether this was something I came up with myself or was something my lecturer shared. When working on my translation, I ran into a bit of confusion with “sa” in the example sentence “umývá sa auto”, which followed the note “for person” after the Slovak verb for “to wash”. As “auto” means car, I was unclear how “sa” could describe a person in this case. Admittedly I turned to Google Translate for answers, which returned the translation “the car is being washed”, using the passive voice in English. I never advanced far enough in my study of Slovak to learn about how the passive voice is constructed, so I can’t say how literally correct this Google translation is, but it is much clearer to me than claiming that “a car washes itself”.

Because “sa” doesn’t perfectly translate into English, that is the one word that remains in Slovak in my TEI/XML translation and is marked using @xml:lang=”slo”, along with one other note where I recorded how the stem of some Slovak verbs change before they are conjugated.

Google Translate still isn’t perfect with Slovak. The verb “obuvať” means “to put on shoes” and is sometimes used reflexively with “sa”. I wanted to confirm my translation of the sentence “On obuvá chlapec” as “He puts shoes on the boy” and found that Google Translate returned the very literal “He shoes the boy”. This, of course, sounds strange in English, and my decision to keep my own translation is consistent with my overall choice to translate correct Slovak grammar into natural-sounding English. Frequently this affected my translation because of the difference in the use of articles in Slovak and English. Slovak doesn’t have indefinite articles and doesn’t use definite articles with the same frequency as English. I supplied articles in my translation where appropriate.

Because of the lack of articles, Slovak sentences are typically fewer words than their English translations. There was one exception to this rule that stood out to me though. Practising using the verb “hrať sa”, to play, I wrote the sentence “On sa hrá na play station”. While prepositions are typically difficult to translate one-to-one, “na” is used in a similar way to the English “on” in many cases. This sentence could translate to “He plays on the PlayStation”, but in English, I opted to omit the preposition and article, which I believe sounds more colloquially correct.

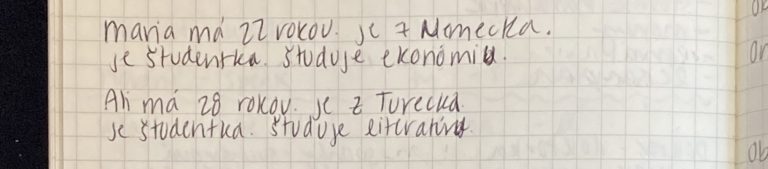

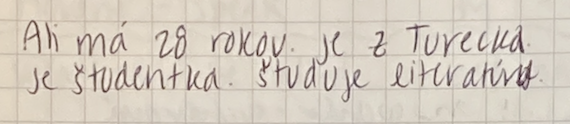

Another notable moment where I chose to translate sentences naturally rather than literally occurs in the first textual division in my document, which lists a couple sentences introducing the ages of different people. In Slovak, the sentence “Maria má 22 rokov” literally means “Maria has 22 years,” which again doesn’t sound quite right in English. I opted for the more natural “Maria is 22 years old” in my translation. Literal vs natural translations were also relevant because of the strength of Slovak verb conjugation. Because verb endings change to indicate the person and number of the verb, often subject pronouns are omitted from sentences. To take an example from the same section, the sentence “je z Nemecka” is literally “is from Germany”, omitting the pronoun “ona” (she) because the previous sentence makes clear who the subject of this sentence is. In my translation, I included the pronoun she to make the sentence complete in English because the sentence lacking a subject in Slovak is perfectly complete.

The only situation where the lack of a subject pronoun can be confusing is in the third-person singular where the present verb form is the same when paired with the sometimes-omitted pronouns for he, she, or it. This happens in the next set of sentences about Ali from Turkey. Ali was a man in my class, but because my sentences lacked subject pronouns, the way to infer what the pronoun would be is from the word “študentka” (student). Because I made the mistake of using the feminine form instead of the masculine “študent” the grammatical assumption would be that Ali is a woman. I preserved my Slovak mistake in my translation and used “she” based on that error.

Another difference between Slovak and English due to the strength of conjugated verbs is the relative flexibility of Slovak word order. I practised this in my notebook when looking at ways to translate the English sentence “I play football on Friday” into Slovak. The conjugated verb “hrám sa” indicates the subject, so other parts of the sentence can be in the first position, and the subject pronoun “ja” does not need to be expressed. The modifier “sa” must come in the second position in the sentence, though, and must always be next to the conjugated verb form.

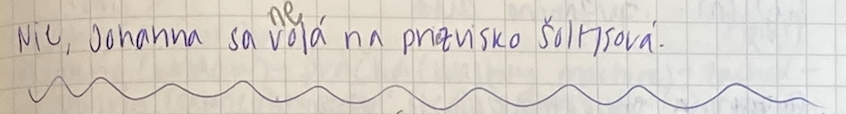

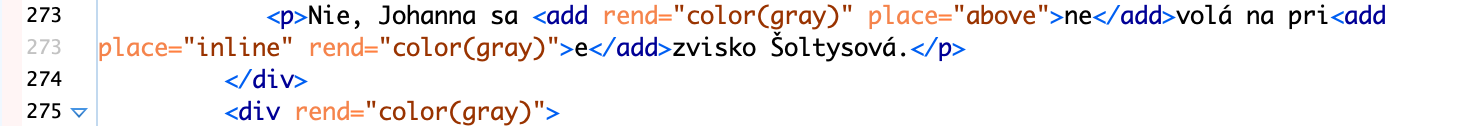

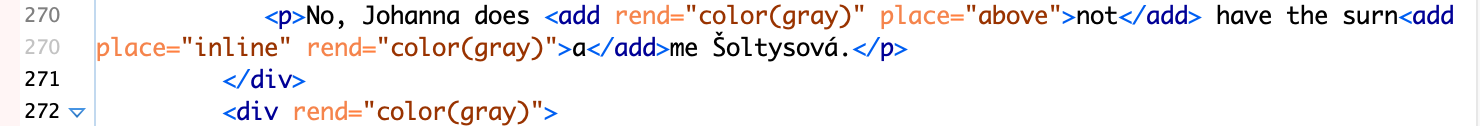

When working on my translation, I was surprised that my encoding was relatively simple to keep consistent across Slovak and English. I only encountered one sentence where I had to change my translation to fit my encoding: “Nie, Johanna sa nevolá na priezvisko Šoltysová”. In this sentence, I corrected “volá” to the negative form “nevolá” and corrected the spelling of “priezvisko” by adding the letter “e” in my notebook.

I represented these corrections using the <add> element.

I would typically translate this sentence, as “No, Johanna’s last name is not Šoltysová”, but to keep the location of the additions consistent across the original and the translation, I translated this as “Johanna does not have the surname Šoltysová”, leaving the “not” and the letter “a” in surname in the addition elements.

As a new language learner, I naturally made many mistakes in my notebook. In this sentence, my instinct is that the preposition “na” is incorrect, as it usually means “on”, but having had a year without using Slovak I am not sure. Because the goal of my edition is to be diplomatic, I preserved mistakes in my transcription and tried to replicate these in my translation. Here, however, I am relying on Google Translate’s “No, Johanna is not called Šoltysová” which does not add an unnecessary “on” and sounds correct in English as the basis for my reinterpretation of the translation.

Other mistakes are clear to me now a year later. Frequently I would forget to conjugate verbs in sentences I was writing. For example, I wrote “Ona sa prechadzať po parku”, leaving prechadzať in its base form instead of the third-person singular form prechadzá. This is reflected in my translation where I use the base form “to walk” in the sentence “She to walk in the park” rather than “takes a walk”. In addition to conjugation mistakes, many spelling mistakes seem to result from my writing quickly, which I replicate with misspellings in my translation. Often, I also omit accents from vowels. I recall that this was partially due to the speed with which I was writing, but also because it was hard for me as an English speaker to hear the difference between accented and non-accented vowels, which made it harder to know when they were used in writing. I was not able to preserve accent mistakes in my English translation because of the lack of accented vowels.

The experience of encoding a diplomatic digital edition of my Slovak language notebook has reminded me of how enjoyable the experience of learning the language was. It was empowering to feel like I understood a little bit more of the world around me after each class, and it was gratifying to show my students that I was making an effort to learn their language as they were learning mine. As a language that is very different to English, I appreciated being able to puzzle through new grammatical structures. In the same way I puzzled through new grammar when I was learning, I had to puzzle through the pages in my encoding. Thinking about the language learning experience through TEI/XML, it was interesting to see how I moved from structured paragraphs, lists and tables and then complicated my pages by adding secondary notes and revisions that made my thinking more thorough and explicit. My focus on creating a diplomatic digital edition helped me better understand the layers of my language learning thought process because of the ways it did and did not easily fit into structured data.