The Presentation of Holy Texts

Wilfried Kuugauraq Zibell, MSt. Yiddish Studies

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. – John 1:1 (KJV)

The relationship between the written word and religion is, for the Abrahamic faiths and the regions where they have historically predominated, inextricable. The interweaving of words and the divine reaches into the very deepest levels of these faiths, and this relationship, both theologically and historically, has shaped the secular world around itself in countless ways. It is only appropriate, then, that the second session of our Paleography course this term focused on the history of the Bible and the presentation of its text.

To begin with, all members of the class were asked to bring in a Bible, resulting in a wonderfully wide array of languages represented. We had a partial Basque Bible translated on the orders of Emperor-President Napoleon III of the Second French Empire, a copy of the original Chinese translation of the Bible, a devotional Bible particularly angled at teenagers which seemed to have had its contents rearranged without rhyme or reason, and many more! While I would’ve liked to have had a copy of the New Testament in Iñupiatun, the native language of my village in Alaska, to bring in, unfortunately (as far as I know) no copy of that translation exists on this continent and so I brought in my serviceable King James study Bible. The smorgasbord of biblical variation, even among those editions published within a relatively narrow band of time, demonstrated the many choices of publishing and translation which make each Bible a fascinating document, both in the history of books and the history of The Book: whether to strive for a vernacular translation or to maintain a high register, whether to include commentary or the text alone.

The class was also treated to a guest lecture by Dr Thea Gomelauri, Founding Director of the Oxford Interfaith Forum and member of the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, on the intricacies of the Jewish scribal tradition. Dr Gomelauri brought in a facsimile of a Scroll of Esther (Megillat Esther), and explained the basics of the halakhically-mandated scribal practices for a scroll to be considered kosher, including precise stipulations for line counts on each page and the spacing between them. These stipulations reflect an estimation of the sacred text not only as a medium for the delivery of holy information, but as an object holy in itself, such that not only the textual information but also the visual impression is considered and cultivated in a particular fashion.

There were three main points of consideration in the text which Dr Gomelauri highlighted: firstly, a section of the book of Esther; secondly, the passage detailing the parting of the Red Sea; and finally Psalm 30. In the book of Esther, which details the plot by the Persian official Haman to have all of the Jewish people in the Persian Empire killed and the foiling of that plot by the Persian-Jewish Queen Esther, there is a section listing Haman’s sons, who were hanged alongside their father on the same gallows he had intended for use against Esther’s people. In every Torah scroll, Dr. Gomelauri informed the class, this list of names is arranged such that the text both visually resembles a gallows and gives the impression of instability, as words are stacked over others of similar length in a technique which the professor called brick-over-brick.

This technique is contrasted with the brick-over-half-brick style of lettering, in which words of various lengths give the visual impression of interlocking stability. It is precisely this latter style which is employed in the section of Exodus which details Moses’ parting of the Red Sea during the Israelites’ escape from Egypt. In the Torah scroll, the very words themselves are parted on the page, a striking visual invocation of the miracle being recounted.

On these sections of the scroll, the walls of text representing the walls of water are themselves written in the sturdy, aforementioned brick-over-half-brick style, so that the reader is struck not only by the miraculous separation of the waters but also the safety this miracle imparted to the Israelite refugees. In neither case did any such stylization exist in any of the translations which the class had brought in, demonstrating the vast differences in extratextual information conveyance even in texts so closely linked.

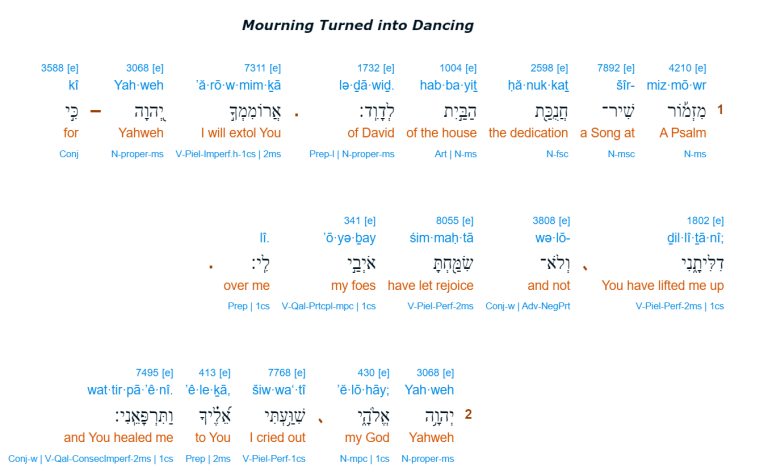

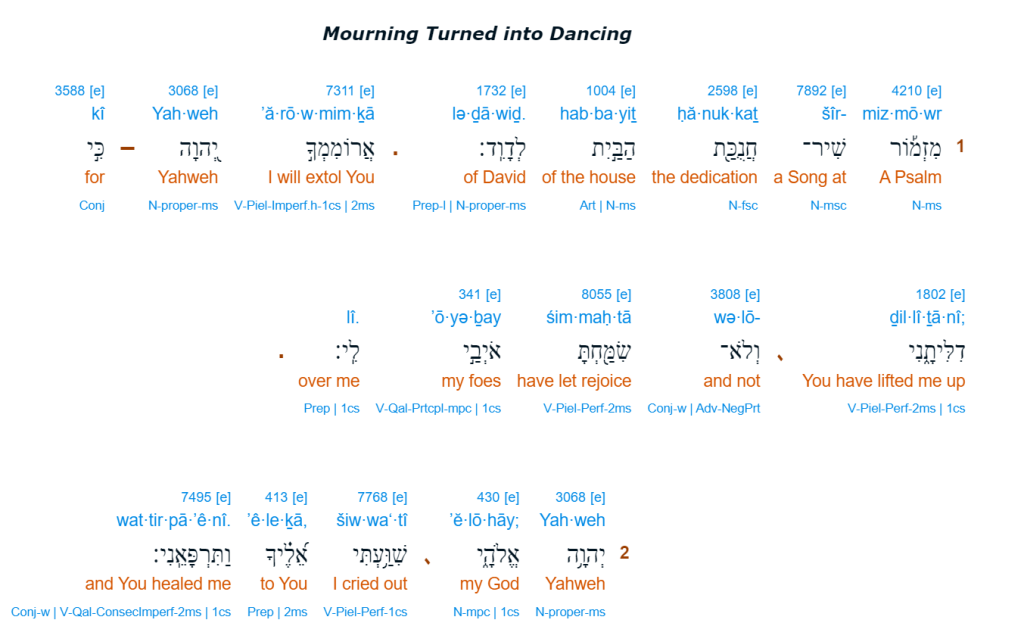

Finally, we focused on the differences in presentation of Psalm 30, whose title is translated variously as “A Psalm. A Song at the dedication of the house of David” (NKJV), “A psalm. A song. For the dedication of the temple. Of David” (NIV), “A Psalm or song of the dedication of the house of David” (1599 Geneva Translation), and even at times omitted altogether. This is notable for several reasons, all centering around the relative importance assigned to the titles of the Psalms as compared to the verses comprising them. Many modern translations of this Psalm, and indeed of the Psalms in general, place these titles in a superscript, not giving them a verse number at all and indicating that they are somehow set apart from the rest of the text. This separation is not at all seen in the original Hebrew, which includes the title as though it were any other part of the Psalm. In fact, once verse numbers were introduced to the Jewish tradition the title of each Psalm was numbered as its first verse, a direct contrast to the practice of many Christian translations (in fact, in writing this blog post I discovered that some online biblical resources do not display the titles of the Psalms at all). This is in part, Dr. Gomelauri informed us, due to a debate as to whether the titles are truly original to the Psalms or are merely a categorization system applied after the fact by some later scribe. Dr. Gomelauri took the case of Psalm 30 to argue strongly in favor of their role as integral to the text along two lines: firstly, that the title of the Psalm seems to bear very little explicit relationship to its content, such that it would be unlikely for a later scribe to apply it on his own initiative and secondly that the literary structure of the Psalm itself only makes sense if one includes the title as a verse. This latter case is based on the structure of the Psalm which, if one includes the title, has 13 verses. Dr. Gomelauri pointed out that in reading the Psalm thusly, a parallelism arises such that the seventh verse acts as an anchor point, and every two verses opposite it (such the first and thirteenth verse, or the third and eleventh) form a single conjoined unit of the Psalmist praising God in a particular way, and hinging on the seventh verse as its fulcrum, being the only one without a parallel and the only one to use a first person pronoun in the original.

As is demonstrated by these examples, not only the content of a text but also its presentation may have massive ramifications on the effect a reader receives, and so both translation and publishing decisions may have a great deal of impact on a text even when striving to reproduce the original as faithfully as possible. How much more impactful, then, do those decisions become when one sets out to translate and publish a holy text?