A report by Marina Giraudeau (Université de Lausanne), Research Intern Michaelmas 2025

When I first met Henrike Lähnemann in spring 2024, I would never have believed the possibility of an internship at Oxford University would actually come true. Yet here I am, spending Michaelmas 2025 in a city vibrant with cultural events, academic opportunities and specialists from all around the world. I arrived with an ambitious project but could not have imagined the scope of experiences that were waiting for me! In this blog post, I will try to shed light on some of them, following on from 10 Rules for an Internship by Philip Flacke.

Working on my project with new eyes

During my preparation for this internship, I had plenty of time to think about the research I wished to complete. My plan was to continue the edition of a prayer book held at my home institution, the University of Lausanne (Switzerland), which I had started working on during my master’s degree. I had already transcribed the first fifty folios of the manuscript and conducted an extensive study of the document’s provenance and history. But the prayer book TP2858 was far from giving away all its secrets, and I was very curious to take a look at the other hundred and ninety folios! For this very reason, an internship in Oxford was a chance I simply could not miss: I would work closely with Henrike Lähnemann, specialist in religious literature and medieval Northern Germany, the region where the manuscript TP2858 was copied. In other words, I was excited for the new term to finally start and had a clear project in mind. That was before I realised to what extent the discussions I shared with students and professors would reshape my thesis!

The diversity of seminars I was invited to attend opened my eyes to interdisciplinary aspects of the prayer book that I had not yet taken into account. My participation in the Medieval Visual Culture Seminar allowed me to connect with art historians – the fruitful exchanges that emerged from these events helped me to consider the prayer book TP2858 in its intermediality. Since the document contains twenty-two miniatures and numerous decorations, ranging from floral elements to illuminated initials, I decided to include a short description of these artworks rather than focusing solely on the text. Furthermore, the Medieval Women’s Writing Research Seminar enabled me to deepen my understanding of female agency through the act of writing. This interested me because I proved that the prayer book had been copied by nuns and was intended for a female audience. There is no doubt that the current state of research on the prayer book TP2858 has been broadened thanks to the many stimulating conversations about medieval texts!

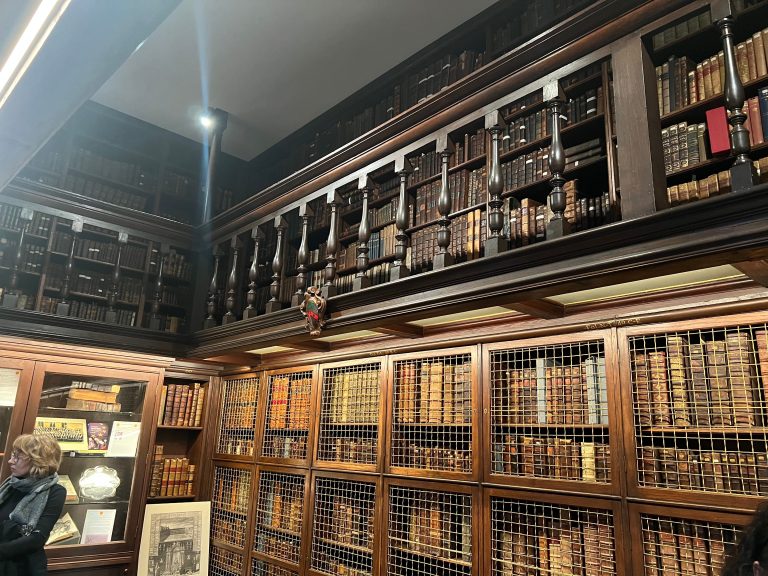

Discovering early printed editions from Germany held at the Bodleian Library

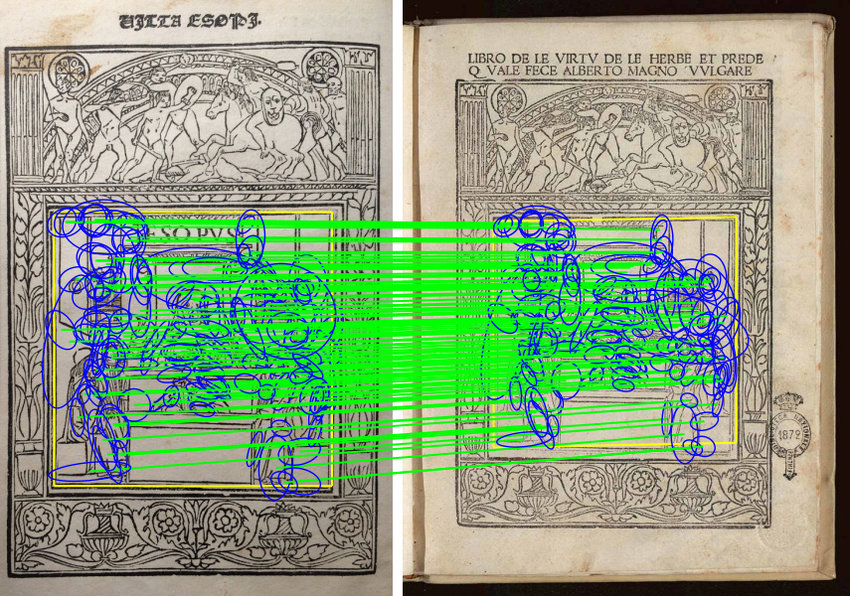

In addition to my own project, I was involved in the eighth edition of the Reformation Pamphlets from the Taylorian. To begin with, I searched Lutheran pamphlets dating from 1525 held at the Bodleian Library – what a specific request! In doing so, I learned to read blackletter typefaces as well as handwritten marginalia. But these case studies were not limited to the text itself: I was determined to find intertextualities and add specific descriptions of the woodcuts printed on the title pages. Through the bibliographic descriptions of the copies I provided, I notably recognised a Latin quotation from Juvenal’s Satires written around a figure appearing on a version of ‘Ermanung zum Frieden’. As I mentioned previously, interdisciplinarity was key to my project, and it appeared to be so for this one too. I therefore tried to take advantage of the new technologies that were introduced to me at the Symposium in Computer Vision and the Humanities. Giles Bergel presented Image Compare application, which I used to clarify the most likely order in which some of the copies were printed by comparing similar title pages.

My interest in German literature flourished in the History of the Book Method Option, as I extended my knowledge of pamphlets over several sessions. For example, thanks to Henrike Lähnemann as well as Emma Huber, I became familiar with the text encoding initiative (the TEI training course by Emma Huber is available online) and attempted to code an excerpt from a Lutheran text for the first time. The workshop that closed this third session turned out to be useful sooner than expected. At the end of November, I decided to update the online edition of the aforementioned Reformation Pamphlet. I focused on the Early New High German text, checking the content of the footnotes and ensuring that the layout was consistent throughout the document. I also inserted a choice option for every abbreviation, so that online readers can view the edited text while knowing what the original transcription looks like. I am very grateful for these two experiences in the context of a published critical edition: they were a valuable complement to the specialisation programme in philology edition that I followed during my master’s degree.

Embracing German texts through materiality and performance

What better way to celebrate the skills acquired than a book launch? On Friday 28th of November, the pamphlet ‘Wider die Rotten der Bauern’ was presented to the public. On this occasion, I volunteered to read a page from the edition, which meant I had to pronounce Early New High German correctly – and dramatically. With the encouragement of some colleagues, I gained the confidence to articulate my text in the spirit of the Peasant’s War. “Put the accent on the adjectives and speak loudly, as if you were in a big theatre!”, added Henrike Lähnemann as I was practicing with her. I followed her advice, and the reading was a success, giving me the impression of a reenactment of the debate that raged in the heart of the 16th century. Performing this pamphlet helped me appreciate the rhetoric Luther mastered to convey his ideas and persuade his audience. Needless to say, I am thinking about the performativity of the prayer book TP2858 and hope to discover new elements of its writing style in the process.

However, that was not the only moment I relived the way books were conceived and enjoyed in the early modern period. I had the privilege to meet Richard Lawrence in his printing realm and customise a Christmas Card. I translated the quote “Peace on earth” into French as well as Swiss German, assembling each letter to form the sentence I wanted. The result was incredibly satisfying to hold in my hands, but was not as marvellous as my realisation of the complex reality and materiality hidden in early prints. Although the time required to produce a manuscript had been explained to me at various conferences, I had surely underestimated the effort necessary to produce a printed text. Moreover, the complementarity between handwritten texts and new printing technology will be a question I will carry back with me to Switzerland: the prayer book TP2858 seems to draw inspiration from printed woodcuts that circulated in northern Germany.

“But why do you study German in Oxford?”

In this blogpost, I have hopefully demonstrated why studying German in Oxford was relevant for me and could be for lots of other projects: a few months ago, I would not have imagined the many opportunities that were going to be offered to me nor the variety of valuable insights Oxford would provide me with in my studies. To all those who questioned my desire to work at this university, asking me in countless different ways why it made sense to study German in an English-speaking country, I trust that these lines will have convinced you of the richness of my stay!