This article was originally posted on the Taylor Reformation blog which has now become part of the Taylor Editions website with a dedicated Reformation Pamphlets series.

Background to the Sendbrief

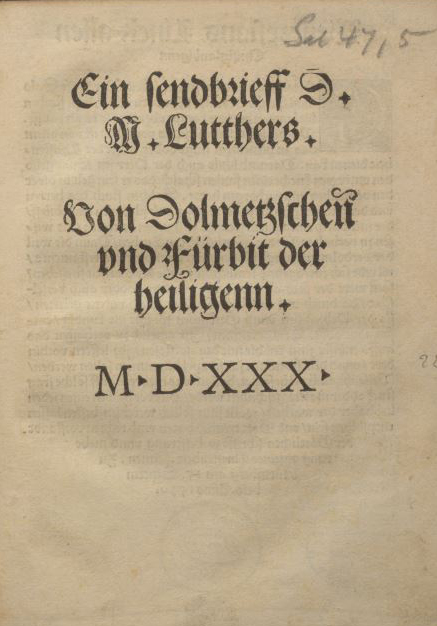

Luther wrote the Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen und Fürbitte der Heiligen in September 1530 at the fortress of the Wartburg, where he had been taken for his own safety under the protection of the Elector of Saxony Johann Friedrich. This was the year of the Diet of Augsburg, at which Luther’s colleague Melanchthon made the first proclamation of Protestantism, the Augsburg Confession.

The pretext for the letter is the fiction that an anonymous friend of Luther’s has asked for guidance on two matters: (i) why Luther inserted the word allein (‘only’) in his translation of Romans 3:28 and (ii) whether the saints intercede in human affairs (Fürbitte der Heiligen). The Sendbrief was triggered by criticisms of his translation by Luther’s opponents.

The Sendbrief is Luther’s most extensive justification of his approach to Bible translation; further views can be found in his Summarien über die Psalmen und Ursachen des Dolmetschens (1531-33), in the prefaces to his Bible translations, and in the Tischreden, which were notes of Luther’s conversations written down by colleagues.

Luther’s Bible translations

Some 3,000-5,000 copies of Luther’s translation of the New Testament were printed in Wittenberg in September 1522 (the Septembertestament); they were sold out within weeks at a price equivalent to a labourer’s weekly wage. A second, revised, edition appeared in December (Dezembertestament) that year. Within a few months versions had appeared in Basel and Augsburg. Between 1522 and 1524 14 authorised and 66 unauthorised versions appeared; from 1522 to 1546 87 High German and 19 Low German editions were published, making a total of 100,000 copies. Luther’s full Bible translation was published from 1534 onwards in six parts. A revised edition came out in 1541 and the last edition revised by Luther appeared in 1546, the year of his death.

Luther’s approach to Bible translation

For Luther, scripture represented a direct link between God and man, without the intermediation of the clergy: ‘Alle Christen/ sein warhafftig geystlich stands/ vnnd ist vnter yhn kein vnterschied’ (An die Radherren aller stedte deutschen lands, 1524). Luther and his colleagues also used scripture as a weapon against the church’s teachings and authority, particularly on the subject of grace and works: many scholastic additions to the scriptures could be exposed as unsupported. As Luther came into conflict with the church, the emphasis on scripture grew into the doctrine of sola scriptura. An accessible vernacular Bible was therefore an essential part of Luther’s theology. Moreover, since a large part of Luther’s audience was illiterate, his translation had to sound natural when read aloud.

The extracts shown here

The first two paragraphs shown here are from the very beginning of the Sendbrief, and the third is part of Luther’s explanation for his use of allein in Romans 3:28. The translation attempts to capture something of Luther’s colloquial style.

Extracts from the Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen

To the esteemed, wise N., my gracious and distinguished friend.

Grace and peace in Christ to you, esteemed, wise, dear, distinguished friend! I received your letter asking me for guidance on two queries/questions. First, why I translated the words of St Paul in Romans Chapter 3, ‘Arbitramur hominem iustificari ex fide absque operibus’ as ‘We consider that man is justified without the works of the law, only by faith’. And you point out by the way how the Papists are getting exceedingly worked up that the word ‘sola’ (‘alone’) is not in Paul’s text and that my addition here to the words of God cannot be tolerated, etc. Secondly, whether the departed saints pray for us since, as we read, the angels do so, etc. On the first question you can (if you like) give your Papists the following answer from me.

First of all if I, Dr Luther, could have imagined that that entire collection of Papists had enough talent between them to produce an accurate, idiomatic translation of one chapter of scripture I’d certainly have summoned up enough humility to ask for their help and collaboration in translating the New Testament. However, as I knew – and the evidence is still before my eyes – that none of them really understands how to translate, nor how to speak German properly, I spared them and myself the bother. But it’s very clear that they’re using my translation and my German to learn how to speak and write German themselves, and in the process stealing my own language from me, a language they knew little about before. Yet instead of thanking me for it they’re far more inclined to use it against me. Still, I don’t begrudge them this at all, because I have to say it flatters me that I’ve even taught my own ungrateful pupils – as well as my enemies – how to speak.

[…]

So when I translated Romans Chapter 3 I was very well aware that the word ‘solum’ doesn’t occur in the Latin or Greek text, and I didn’t need a lesson from the Papists to tell me that. It’s a fact: these four letters s-o-l-a are not there – the four letters that those oafs are gawping at like cows before a new gate. But they don’t see that this word nonetheless captures the meaning of the text, and if you’re aiming for a clear, vigorous translation, it belongs here – after all it was German, not Latin or Greek that I was trying to speak, given that I’d set out to produce a translation in German. That’s the way it’s done in German when talking about two things one of which is affirmed and the other denied – you use the word ‘solum’ (‘only’) along with the word ‘not’ or ‘no’. It’s the same when you say, ‘The farmer is bringing only grain and not money’, or ‘No, I haven’t got any money but only grain’, ‘I’ve only eaten and I haven’t had anything to drink yet’, ‘Have you only written it out and not read it over?’ – and countless similar expressions in everyday usage.

Dr Howard Jones

College Lecturer in Linguistics

Keble College