On the 500th anniversary of their first publication, the first of the four hilarious, successful and witty Reformation Dialogues by Hans Sachs is reissued in a new edition. This includes a new English translation, a historical introduction, linguistic footnotes, and also the 15th century Dutch and English translations. The launch event comes in three parts, both on Friday, 1 November 2024

- 10.45-11am, Weston Library, Visiting Scholars Centre: Pamphlet presentation during the Medievalists Coffee Morning.

- Items exhibited

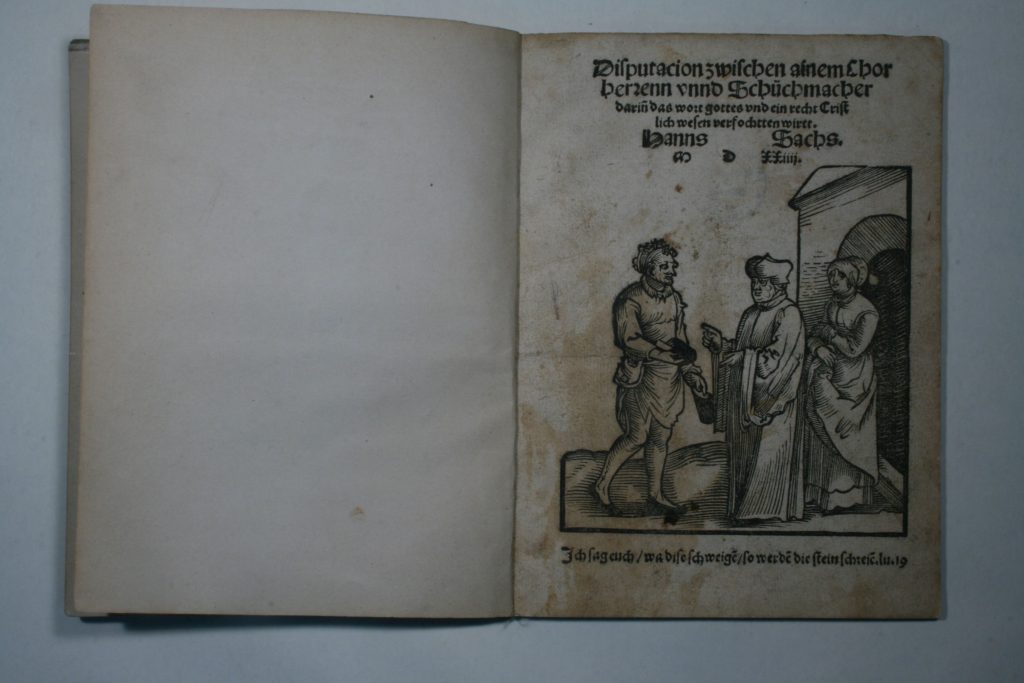

- Tr.Luth. 34: A Sammelband with nine copies of different editions of the four 1524 dialogues by Hans Sachs

- a number of home-made facsimiles of the dialogues for ‘spot the difference’

- Vet. A1 f.237: ‘A goodly dysputacion’, the English translation of the first dialogue

- Douce Fragm. f.22: Same edition, last quire only

- Tr.Luth. 50: A Sammelband which contains a 1527 illustrated pamphlet with verses by Hans Sachs Ein wunderliche weissagung von dem Bapstumb, wie es yhm bis an das ende der welt gehen sol, ynn figuren odder gemelde begriffen, gefunden zu Nurmberg. Ein vorred A. Osianders. Mit gutter verstendlicher auslegung, wilche H. Sachs yn deudsche reymen gefasset.

- Following this, the Print Workshop at the Bodleian Library will be open 11.30-12.30 for a chance to print an extract of the German dialogue, typeset by Oxford students in black letter.

- 5-6:30pm, Taylor Institution Library (St Giles, Oxford), Room 2: Launch of the edition which featured live performances of part of the first dialogue in early modern German, early modern Dutch, and early modern English.

Watch the launch

The new edition is volume 7 of the ‘Reformation Pamphlets’ series of the ‘Taylor Editions’, with introductory chapters by Philip Flacke, Henrike Lähnemann, Jacob Riley, and Thomas Wood. Ebook of the publication (and as a side-by-side version). The volume is also available on Google Books. Download this pdf-reconstruction of the original quires to make your own Reformation pamphlet (print on A3, double-sided, then fold and cut).

Introductory Chapters as Blogposts

- The Historical Context (Tom Wood)

- English Reformation Dialogues (Jacob Ridley)

- The Pamphlets in Oxford (Philip Flacke)

- The Edition (Henrike Lähnemann) including the general introduction and the bibliography

Digital editions:

- Sachs, Hans Disputacion zwischen ainem Chorherrenn vnnd Schüchmacher dariñ das wort gottes vnd ein recht Cristlich wesen verfochtten wirtt. M. D. XXiiii [1524]

- Sachs, Hans Een ſchoon | diſputacie van eenē Euā- | geliſſchen Schoenmaker | ende van eenē Papistigen | Cooꝛheere / met twee | ander perſonagiē | gheſchiet tot | Norēborch. | Ghedꝛuckt by my Magnus | vanden Merberghe. [s.l.:] Magnus van den Merberghe, [c.1545]. (coming soon)

- Sachs, Hans / Scoloker, Anthony, A goodly | dyſputacion betwene a Chꝛi-|ſten Shomaker / and a Popyſſhe Par-|son with two other parſones more, | done within the famous Citie | of Norembourgh. | Translated out of yͤ Germayne | tongue into Englyſſhe. By | Anthony Scoloker. London 1548

- Sachs, Hans; Osiander, Andreas Eyn wunderliche Weyssagung / von dem Babstumb / wie es yhm biß an das endt der welt gehen sol / in figuren oder gemaͤl begriffen / gefunden zu Nuͤrmberg / ym Cartheuser Closter / vnd ist seher alt. Nuremberg: Hans Guldenmund, M. D. xxvii. Jar. 1527

Recordings and other audio-visual material

Recording of the first of the Reformation dialogues by Hans Sachs. Chorherr: Konstantin Winters. Schuhmacher: Linus Ubl. Köchin: Henrike Lähnemann.

Reposting from a blog by Charlotte Hartmann on Hans Sachs in Oxford

The Disputation zwischen einem Chorherren und Schuhmacher, the first of Hans Sachs four Reformation dialogues was by far the most successful. The pamphlet’s enormous popularity is proved both by the noticeable number of eleven different printed editions in 1524 alone and the fact that it was translated not only into Dutch, but also into English (A goodly dysputacion betwene a christen shomaker, and a popysshe parson). Sachs’ publisher and printer was Hieronymus Höltzel, who produced the first prints of the last three dialogues, whereas this dialogue was first printed by Gustav Erlinger in Bamberg – possibly for the reason that reformatory publications in the city of Nuremberg, Sachs’ hometown, were subject to strict censorship at the time.

The dialogue features a lively debate between a canon and the shoemaker Hans, which centres on the principal question as to the say of laymen in clerical and theological discussions. Sachs coquets with his recently attained fame through the publication of his allegoric poem Die Wittembergisch Nachtigall (1523) when the shoemaker casually notes the cleric’s nightingale, which eventuates in a temperamental outburst of the canon. The opponents are unevenly matched: From the very beginning the figures are characterised by their manner of speaking. The author satirically targets the contrast between the shoemaker’s respectful, polite salutation and the canon’s distinctly ‘sloppy’ remarks. It quickly becomes obvious that the Lutheran craftsman, who is very well-versed in the Bible, outperforms the canon by far. The argumentation of the latter seems to result chiefly from his insistence on traditional privileges, underlining the concern for his own comfort. Not by chance does Sachs frequently refer to the canon’s pantoffel, which are a symbol for the comfortable and easy life he leads. Throughout the discussion the shoemaker’s sober reasoning leaves the canon unconvincing and helpless.

The use of the dialogue form in pamphlets was not new. Especially in the early 1520s the dialogue experienced a striking heyday. This fomenting genre offered the opportunity to depict the process of opinion-forming and simultaneously influencing it. Nevertheless, Hans Sachs’ Disputation zwischen einem Chorherren und Schuhmacher was particularly significant, owing its enormous popularity to its distinctly vivid style of conversation and character depiction and its numerous reproductions, which were fuelled by the controversial prominence of Luther’s conception of lay priesthood.

Tr. Luth. 34 (57)- ARCH.80.G. 1524 (26) – Tr. Luth. 34 (56)

Two of these three woodcuts look much alike, whereas one seems to clearly differ from the others. It was common practice for designers of woodcuts to trace existing woodcuts, using thin sandwich paper. This image was then transferred. It can be assumed that these reproduced woodcuts were not refined, since reprints were mainly expected to be cheap and quickly available while looking as alike as possible. A slightly longer coarser nose can therefore be an indication that this woodcut was a later copy made from an older woodcut.

Which differences can you find? Which one do you think is the oldest/youngest?

1 thought on “Hans Sachs in Oxford”