By Thomas Wood

This is part of a series of introductory posts for the updated edition and translation of Hans Sachs’s first Reformation Dialogue ‘Chorherr und Schuhmacher’ (‘Canon and Cobbler’) in German (1524), Dutch (1540s), and English (1540s), published as Volume 5 of the Treasures of the Taylorian. Series One: Reformation Pamphlets. Ebook of the publication.

- The Historical Context (Tom Wood)

- English Reformation Dialogues (Jacob Ridley)

- The Pamphlets in Oxford (Philip Flacke)

- The Edition including the Bibliography (Henrike Lähnemann)

Related Taylor Editions

- Hans Sachs: Disputation zwischen einem Chorherren und Schuhmacher (1524)

- Een schoon disputacie (the Dutch translation of the early 1540s, coming soon)

- A goodly dysputacion (the English translation of the 1540s)

- Hans Sachs’s other 1524 dialogues (coming soon)

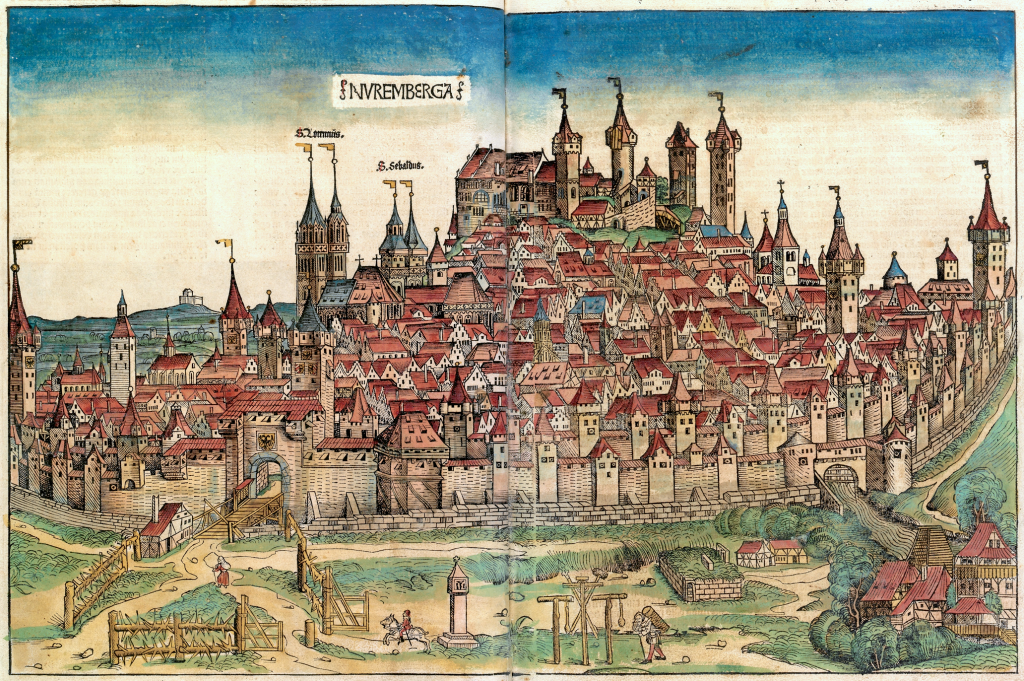

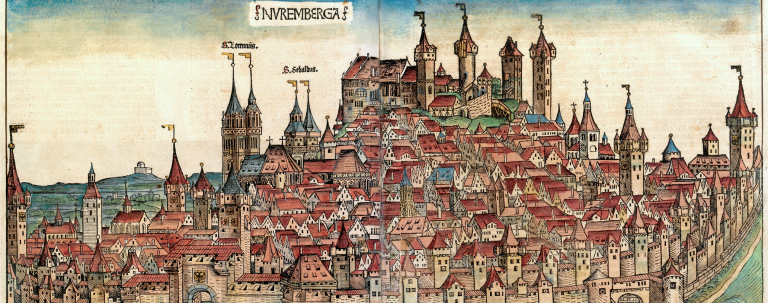

Situated on the river Pegnitz in the heart of the Holy Roman Empire, the Nuremberg of Hans Sachs was a thriving Free City that acted in 1524 as a site of both Imperial power and religious conflict. In the late Middle Ages and into the sixteenth century, Nuremberg had been a prosperous city sitting upon a trade route between the Italian City States and the ports of the Hanseatic League with many flourishing trades and a vibrant intellectual culture. Thus goods and ideas from across the world passed through the city which itself would become a major exporter of commodities and culture. From arms and armour to sophisticated scientific instruments, all manner of wares flowed from the workshops of Nuremberg whilst great luminaries of the German renaissance such as Albrecht Dürer, Adam Kraft, and Veit Stoß called the city their home. Over the centuries Nuremberg had become a nexus at the heart of the European continent, an ideal melting pot for new ideas and dissent against the existing religious order to brew, and when the Reformation swept through the German-speaking lands over the course of the 1520s, Nuremberg was ripe for reforming.

Indeed, Nuremberg had a thriving community of humanists who were not only initially receptive to Martin Luther’s ideas, especially the adoption of vernacular Bibles, but also served on the city council. The council served as de facto rulers of Nuremberg, overseeing the prosperity of this trading city and investing heavily in its future. They scrutinised every aspect of life in the free city and their religious convictions would dramatically alter the course of Nuremberg’s future in the sixteenth century. Council members and leading figures in the city governance sympathetic to Luther in the early 1520’s would include Christoph Scheurl, Wenceslaus Link, Lazarus Spengler,1 Willibald Pirckheimer, Hieronymus Ebner, Kaspar Nützel, Clemens Volckamer, and Christoph Kress. Some of these men were particularly close to Luther, Link being a close personal friend while Spengler and Pirckheimer were even threatened alongside Luther with excommunication in the papal bulls of 1520 and 1521. Though the former would serve as secretary to the council and be influential in the events of 1524 and 1525, Pirckheimer meanwhile, alongside Scheurl, would ultimately side with the Catholic establishment. Those Nuremberg humanists that stuck with Luther would develop strong Protestant convictions that saw the city formally adopt Protestantism in 1525, aided in their endeavours by the theologians of the city.

As well as humanists within Nuremberg’s governance who were receptive to Luther’s ideas, many of the religious authorities within the city were also of a Reformation spirit. The sixteenth-century skyline of Nuremberg was characterized by the double spires and ‘Buckelchor’ (high Gothic choir) of its two parish churches, St Lorenz, and St Sebald, the latter named after the patron saint of the city. Within these institutions the Protestant spirit had taken hold in the years leading up to 1524. In 1522, Andreas Osiander would be appointed to St Lorenz after having worked for the previous two years as a Hebrew tutor at an Augustinian convent. A proud and defiant Lutheran preacher, Osiander was involved in multiple high-profile cases of religious controversy and conversion over the course of his life. By 1524 he had notably converted Albert of Prussia, Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, to Lutheranism who would go on to found the Duchy of Prussia and make it the first land to officially adopt Protestantism as the state religion, and in 1525 he would be the Protestant leader of the debates which led to Nuremberg formally adopting the Reformation as first Imperial Town. Meanwhile, at St Sebald, Dominicus Schleupner had taken up residence at the recommendation of Luther from which he became a leading voice of reform in the city, giving the opening speech at the 1525 debates. These eminent preachers at the city’s two major churches were supporters of the Reformation and persisted in their Protestant teachings despite pressure from Imperial authorities.

Indeed, the pro-Reformation slant of the city’s authorities can be seen in their lax approach to enforcing the Edict of Worms, posting a copy of it at the town hall in 1521 while continuing to appoint men like Osiander and Schleupner to office. The council of Nuremberg had long preferred to manage religious affairs within their territory, existing in constant fractious struggle with the nearby Bishop of Bamberg who was ultimately ineffective at asserting his authority over the free city in his diocese. The zeal for reform did however find itself tempered somewhat in the early 1520s by the presence of the Imperial Diet in Nuremberg, its first session 1522 and its second in 1524, which saw the Imperial Governing Council, Imperial Chamber Court, and papal delegation stay in the city. This mass gathering of Catholic authorities in the city saw the council of Nuremberg forced to balance the demands of those who opposed Luther’s ideas with their own pre-Reformation tendencies. Indeed, Francesco Chieregati, the papal nuncio, demanded that the council only allow the printing of anti-Lutheran pamphlets. The council reluctantly censored the presses, but refused Chieregati’s request to arrest preachers, instead merely advising them to avoid controversial topics in their sermons while the Diet was in the city.

When the Diet left the city in April 1524, the spirit of the Reformation began to be expressed more freely, not only from the pulpits of St Lorenz and St Sebald, but also from the presses and on the streets. This emboldened the Lutherans in the city, and it also attracted more radical religious reformers with whom they would dome to be at odds. Many religious radicals either lived in or passed through Nuremberg in 1524, carrying their ideas throughout the Empire across the trade routes that ran through the free city. In the prior century Jan Hus had stayed there on his fateful journey to the Council of Constance, and many others would pass between the city gates in 1524 who had similarly violent ends. Notably, Thomas Müntzer briefly visited the city in the latter half of 1524, maintaining a low profile and spending just enough time in the city to print a defence of his position aimed at Luther and his Wittenberg disciples before heading southwest where the first murmurings of the German Peasants Revolt could be heard. Müntzer’s pamphlet, A Highly Provoked Vindication and Refutation of the Unspiritual Soft-Living Flesh in Wittenberg Whose Robbery and Distortion of Scripture Has So Grievously Polluted Our Wretched Christian Church served as on open letter to Luther that accused him of betraying his original vision of reform in favour of the nobility and at the expense of the peasantry.2

This incendiary pamphlet never made its way to distribution however. Müntzer had left Heinrich Pfeiffer in the city to disseminate this work while he moved further afield, but Pfieffer was quickly expelled from Nuremberg and the council suppressed Müntzer’s pamphlet following the advice of Osiander, who would regularly offer his opinion on religious pamphlets when asked by the council while he preached at St Lorenz.

Similarly, the council would suppress the work of Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt. A former leader of the Reformation in Wittenberg and a friend of Luther as well as many Nuremberg humanists, Luther would eventually denounce him as a radical in 1524 and he would be expelled from Saxony in September. Though Karlstadt would not join Müntzer, his unfavorability with Luther would colour Nuremberg council’s response to his associate Martin Reinhart, who attempted to have the exiled reformers’s work published in the city. The publisher, Hieronymus Höltzel, would be arrested by the authorities and Reinhart was expelled from the city. Once more, the works of those disowned by Luther himself were censored by the council who cleaved more closely to the ideas espoused at Wittenberg.

Other religious radicals included the preacher Diepold Peringer who operated in the suburb of Wöhrd in the city c.1523-4. The Baptist Hans Hut regularly visited the city as a bookbinder in the 1520’s and was in contact with Müntzer whilst he visited Nuremberg. Similarly, Anabaptist leader Hans Denck arrived in Nuremberg in 1523, acting as headmaster of the St Sebald church school but was banished from the city after coming into contact with Müntzer and adopting many points of his radical theology. While the council was keen to break from Catholicism, they did not wish to be seen to allow radicals, who might discredit the new faith, to thrive. Eventually however, the Protestants of Nuremberg would get their wish when the city formally adopted the Reformation in 1525. While councillors and theologians like Christoph Scheurl and Andreas Osiander were pivotal voices in the religious debates that engulfed the city, Nuremberg was also a centre of pamphleteering undertaken by the artisan strata of society. These pro-Lutheran artisans would proliferate the ideas of the Reformation in their own ways and counted amongst their number men such as Hans Sachs.

Hans Sachs was born in Nuremberg in 1494 the son of Jörg Sachs, a tailor, and would go on to become a celebrated Meistersinger, poet, and playwright who was deeply involved in the Reformation in Nuremberg. Sachs attended Latin school in the city as well as apprenticing as a shoemaker there before undertaking the customary years of training in other places at the age of 17, leaving Nuremberg in 1511. During this period of his life Sachs would travel across the length and breadth of modern-day Germany and Austria practising his trade before a chance encounter with the retinue of Emperor Maximilian I in Wels, where Sachs had settled in 1513 to study the fine arts, saw the young shoemaker join the Imperial court. He would then for a time be situated in Innsbruck, before quitting the court in 1515 and beginning an apprenticeship under Lienhard Nunnenbeck as a Meistersinger in Munich. After five long years travelling as shoemaker and Meistersinger, Sachs would move back to his home city of Nuremberg in 1516 where he would remain for the rest of his life, practising both his crafts and enthusiastically engaging with the Reformation. He was married twice, first to Kunigunde Creutzer in 1519 with whom he had seven children that Sachs would sadly outlive, then later to the widowed Barbara Harscher with whom he had no children, marrying her the year after Kunigunde’s death in 1560. Sachs himself would die in 1576 and be buried at the Nuremberg Johannisfriedhof.

In his lifetime Sachs produced a vast quantity of works, many in Knittelversen, including more than 4000 mastersongs, over 2000 poems, and a great multitude of tragedies, comedies, carnival plays, dialogues, fables, and various kinds of religious tracts. He was immensely popular in his own time, and after being largely forgotten some time after his death, Sachs’s memory was revived by artists and scholars in the eighteenth century. His extensive works continue to be performed and analysed to this day, especially those works which pertained to Sachs’s support of Martin Luther.

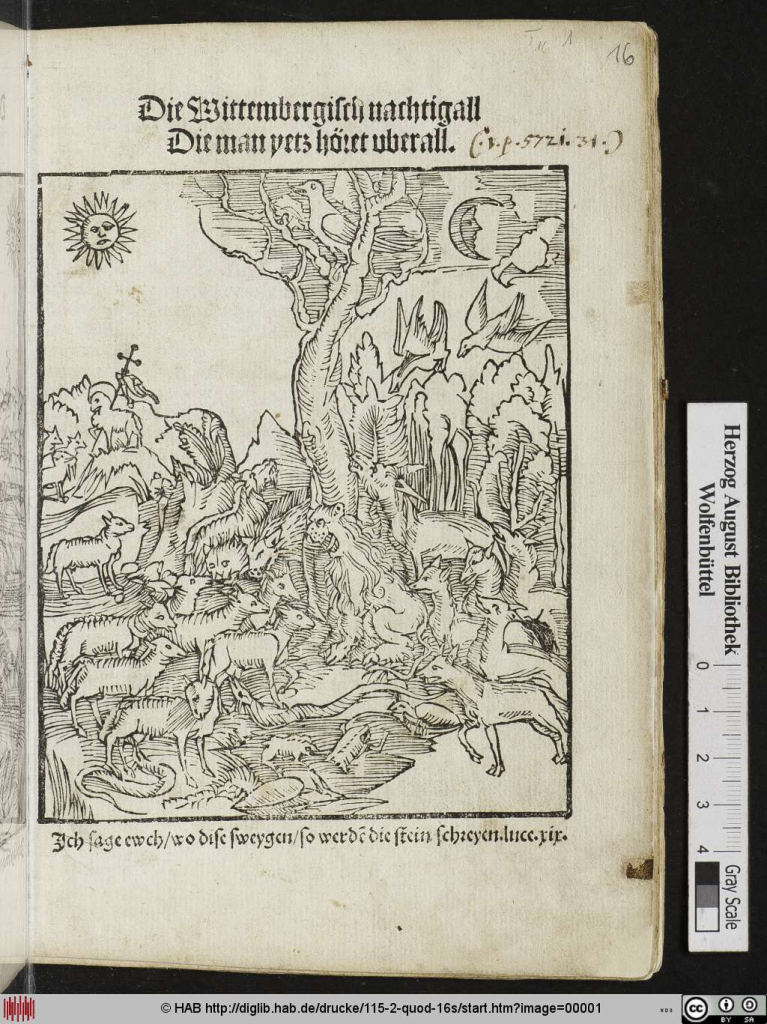

Foremost of these religious works was his 1523 poem written in Luther’s honour ‘The Wittenberg nightingale, now audible everywhere’ (Die Wittenbergisch Nachtigall, die man jetzt höret überall).

This new poetic voice for Lutheranism is perhaps the most famous artisan pamphlet of the German Reformation, both in terms of its contemporary reception and its historical legacy. In this piece Sachs encouraged his audience to ‘wake up’ and listen to the ‘joyous nightingale’ of Wittenberg who preached the truth to the German People. Indeed, Sachs accused the pope and his servants of using their powers to exploit and oppress simple Germans, depriving the laity of the gospel, and enacting a tyranny over both the conscience and pocketbooks of common folk. This blistering attack on the upper echelons of the Church was placed alongside a dramatic vision of Luther as a liberating figure who was not only in the right, but also simply could not be stopped. The work was as resonant as it was inflammatory, published as it was in the atmosphere of religious turbulence in Nuremberg.

A year later, Sachs published the four prose dialogues. Written and published as Nuremberg was escaping the yoke of the Imperial Diet, as the council clamped down on religious radicals, and in the time immediately preceding the religious debates of 1525, these dialogues are not only an expression of Sachs’s own religious views but also of the Reforming zeal that had gripped the free city. They concern themselves with many of the most important topics of religious debate in the 1520s such as the abuses of the Church’s power, monastic vows, the nature of salvation, Christian liberty, and lay access to and interpretation of scripture.

The first of these dialogues depicted a discussion between a shoemaker and a canon that ranges across many aspects of Luther’s theology. The character of the shoemaker, sharing his profession with Sachs, is able to deftly and consistently counter the arguments of the canon with his scriptural knowledge whilst praising the work of Luther. The customary format of the early modern dialogue is used to great effect here as the usual authoritative roles are inverted and the canon takes on the asking role of the student whilst the shoemaker takes on the answering role of the teacher. It on this final point that Sachs perhaps speaks in these dialogues to a prevailing school of thought amongst the people of Nuremberg, and it is perhaps unsurprising that the first dialogue’s focus on scripture would in many ways foreshadow the nature of the debates of 1525.

These debates were held in the Great Hall of Nuremberg’s city hall between the 3rd and 15th March 1525. The talks were led by Christoph Scheurl, and were inspired by the 1523 Zurich Disputations which had ultimately seen the council of Zurich adopt the Reformation. The Nuremberg council allowed only the Bible as evidence in these discussions, disallowing appeals to canon law or references to Church tradition, not unlike the shoemaker of Sachs’s fictional disputation published the year prior. This approach heavily favoured the sola scriptura approach of the Protestant faction who were foremostly represented by Andreas Osiander and Dominicus Sleupner. These leading figures of Nuremberg’s premier religious institutions took centre stage as advocates for the Lutherans alongside Wolfgang Volprecht, the last prior of Nuremberg’s Augustinian monastery, which had been an early adopter of Reformation ideas. Opposing them were a number of Catholic preachers, many with monastic backgrounds, notably the Franciscans Lienhard Ebner and Michael Fries. A victory for the Protestants in these debates was eventually proclaimed and on the 21st April Catholic Mass was banned in the city of Nuremberg. The council proceeded to institute Protestant preaching in all churches in the city and undertook a policy of closing all monasteries in and around the city. Some, like Volprecht’s Augustinians, dissolved themselves, others who, like the Poor Clares led by Caritas Pirckheimer as abbess, vigorously resisted the movement, were banned from accepting new members and were eventually dissolved once the last members of the community left or died.3 So came the end of Catholicism in Nuremberg, public opinion in the city having been swayed not just by the preaching of men like Osiander, but also by the popular publications of artisans like Hans Sachs whose works would go on to be exported across the rest of Christian Europe.

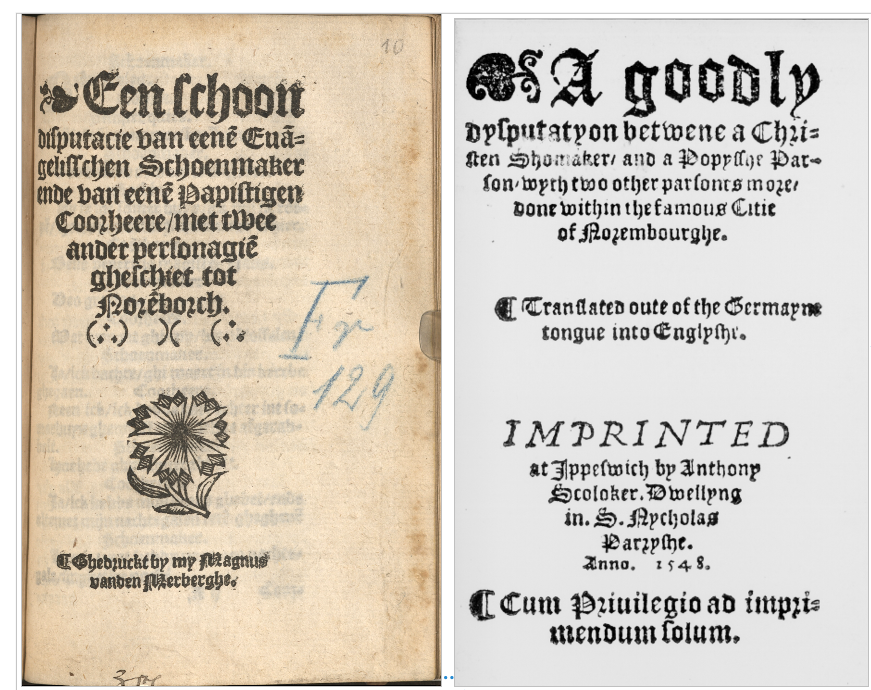

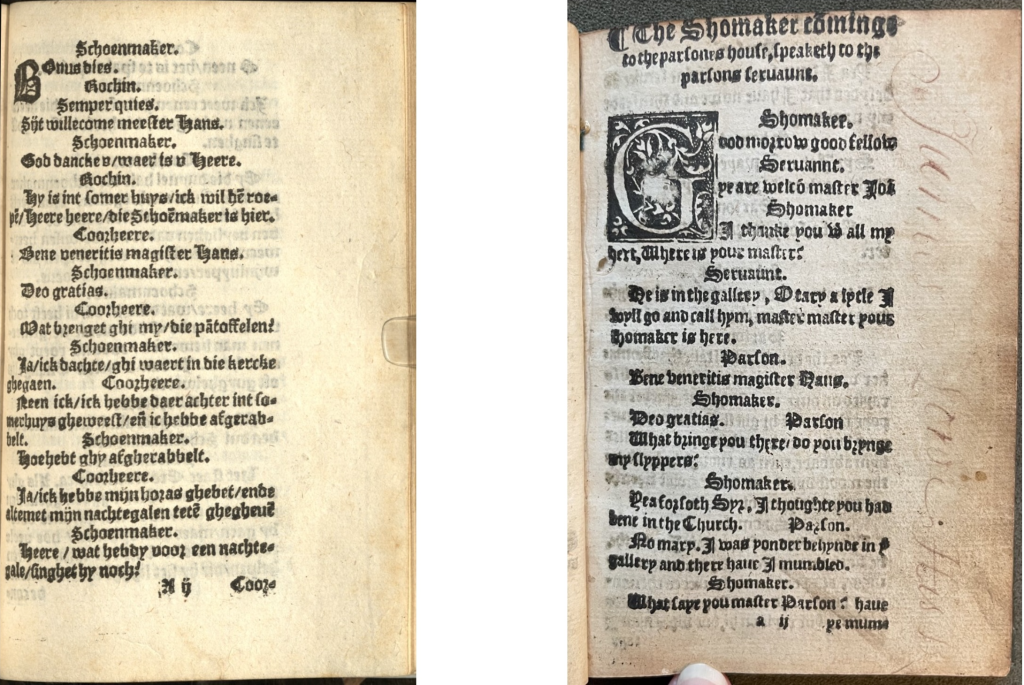

As far as we know, Sachs’s first dialogue is the only one that was translated, first into Dutch and published by one Magnus vanden Merberghe, a pseudonym that has come to be associated with Frans Freat (d. 1558).4 Our edition has no date, owing to one of Fraet’s practices of reprinting earlier works as well as the habit of Protestant Dutch printers to obscure the true authorship of their works (including printing false dates) in order to escape the censors.5 Though unclear as to who did the original Dutch translation that Merberghe printed, the Dutch version of Sachs’s dialogues follows the German closely (see footnotes in the edition on Germanisms). A few differences do arise such as the Dutch version being laid out differently with the speakers given their own clearly demarcated lines – a change that the English version would carry forward. The Dutch text then made its way into England at some point before 1546, owing to a thriving trade of printed materials between print centres like Antwerp and London.

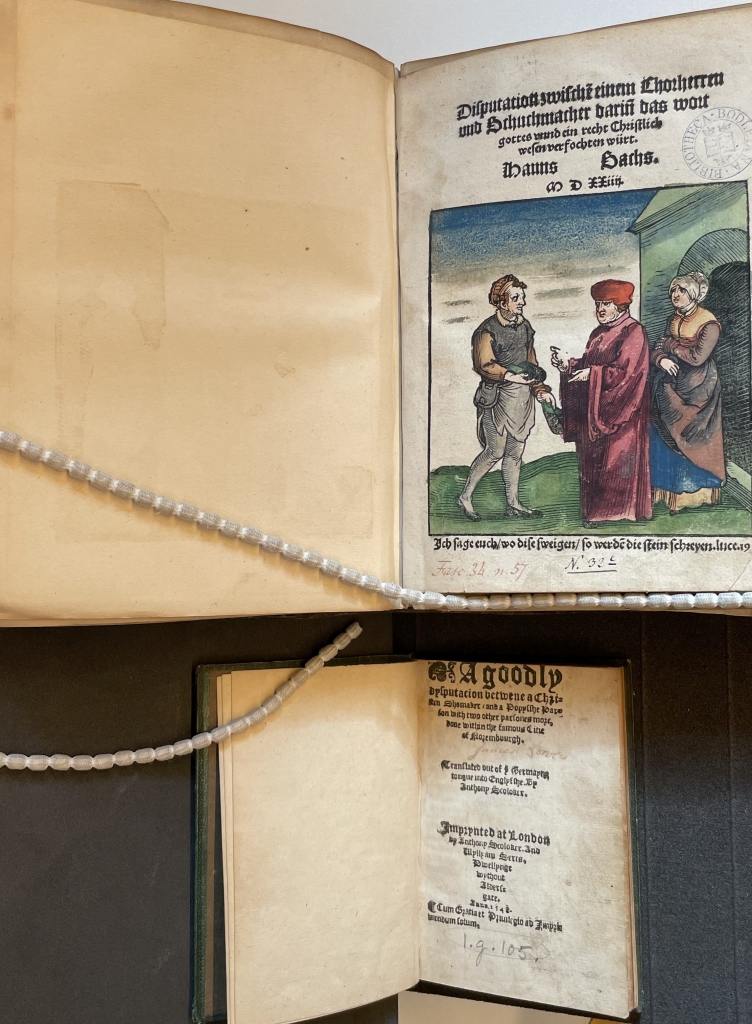

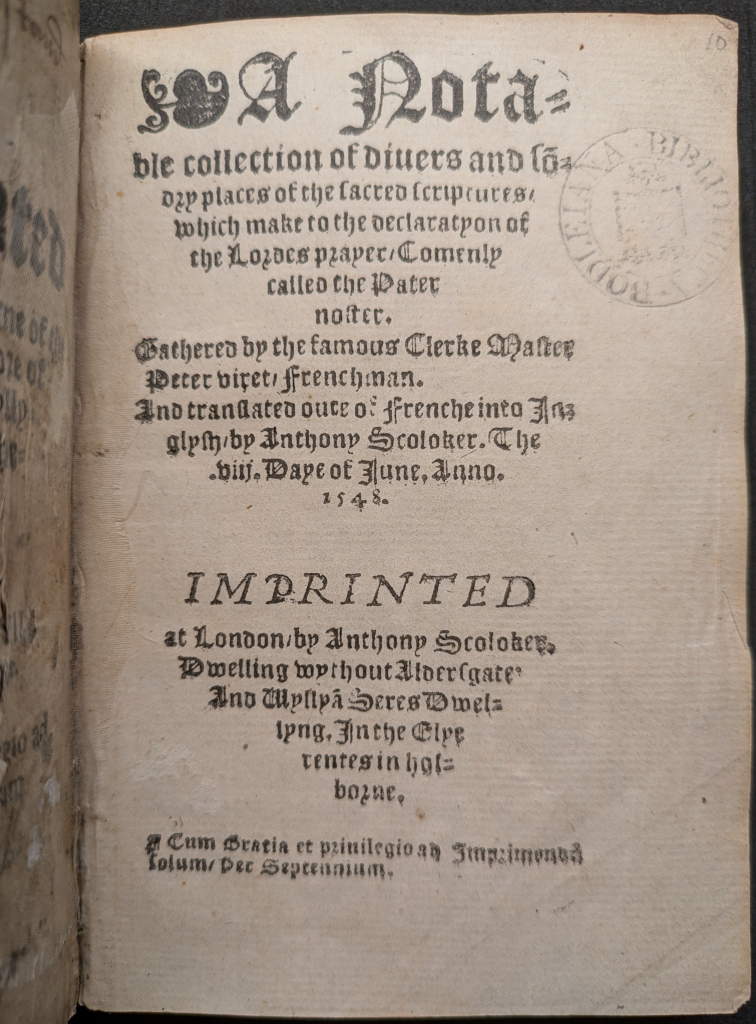

In any case, this Dutch edition was in turn translated into English; our edition is based on one of the editions from 1548 (see below) but it must have been in circulation earlier, since the same title was put on the index during the reign of Henry VIII: ‘A Godly disputation betwene a Chrysten Shomaker and a popish persone’ in 1546.6 The actual proclamation specifically bans works by ‘Frith, Tindall, Wicliff, Joy, Roie, Basile, Bale, Barnes, Couerdale, Turner, Tracy, nor any book contrary to the King’s ‘A necessary doctrine and erudition for any christen man’, or any book prohibited in that Parliament.’7 The 1548 English version, a new edition or reworking of this pre-1546 edition, is published twice, the first in Ipswich, the second later that same year in London, to which the two copies of the Bodleian belong. As usual for Dutch and English pamphlets, the size is octavo, while German pamphlets are usually printed as quartos. The other difference is that there are no woodcuts, only printer’s ornaments; the English editions clearly modelled on the Dutch choice of a floral leaf opening the title, with the Dutch adding in some punctuation types arranged as an ornamental line and a flower.

Both of these editions contain the same textual content and layout, though the type has been reset between the Ipswich and London printings, visible already in the title layout. They are, as most Dutch and English pamphlets, in octavo format, without a title woodcut, and they leave out the author’s name, only stating that it was written in Nuremberg. The Dutch claims at the end that this is an incident that happened in 1522 (D8r). While the German edition typesets the dialogue as running text, probably because in the quarto format it would waste too much space, the speakers get their own, indented lines in the Dutch and English.

Ill. 6: Above: The first edition Bamberg: Georg Erlinger, copy: Bodleian Tr. Luth. 34 (57). Below: The London edition of the English translation by Anthony Scoloker 1548, copy: Bodleian Library, Vet. A1 f. 237

The man responsible for bringing Sachs to England, Anthony Scoloker (d. 1593), was a printer who established Ipswich’s first printshop c.1547 and was active there and in London during 1548 before seemingly leaving the print trade. Not much is known of Scoloker’s life as scant bibliographic details about him have survived; he is therefore known to us only through the materials he published in this short period. Indeed, what he chose to publish were religiously pro-Reformist works, many by continental reformers like Martin Luther and Zwingli, suggesting a Protestant faith and understanding of continental print culture.8 Scoloker printed a number of these works at Ipswich, some in collaboration with Richard Argentine , before moving to London halfway through the year, after which John Oswen (fl. 1548) took over (it is unclear if Oswen worked at the same time as Scoloker or only came to Ipswich after Scoloker had left) before leaving Ipswich himself for Worcester the next January, leaving Ipswich without a printer until 1720. Ipswich had easy access to the continent as a thriving port town and it has been suggested Scoloker himself had strong ties to continental Europe, with signed translations from German, Dutch, and French.

A 1549 Middlesex Subsidy Roll counts him as an ‘Englysmen’ rather than a foreign visitor to the country, suggesting that his language expertise may have been a result of him having spent time on the continent, perhaps in religious exile under Henry VIII, or at least had significant ties to continental trade that passed through Ipswich and London. Scholars have suggested that, whether any such travels on the continent prior to his appearance in Ipswich were a religious exile, for mercantile purposes, or any other form of travel, he was possibly associated with the Ghent printer and typefounder Joos Lambrecht who may have given Scoloker his type and pictorial woodblocks.

All the books that mention Scoloker by name place him as active in Ipswich and London c.1547-48, or are otherwise undated (possibly being printed in 1549), making his life before this flurry of printing activity unclear and his life after his appearance in the Subsidy Roll of 1549 equally vague. References to his various addresses in London in his publications see him move across the city before his publications suddenly cease.9 Whatever his reasons, Scoloker does not seem to have printed again, at least under his own name, and his activities during the next two decades are unknown. He may have chosen to abandon the trade after censorship laws were re-scrutinised in 1549, left England as a religious exile after the accession of Mary I in 1553 as some other Protestant printers did, or simply changed profession and never returned to printing for personal or financial reasons. Indeed, a merchant Anthony Scoloker is named in the 1567–8 London Port Book as receiving shipments of small goods including lute strings whom historians have suggested, in no small part due to the uncommon nature of the surname, to be the same individual as the Ipswich printer.10 Given the profession of ‘milliner’, this Scoloker was importing goods from Antwerp suggesting that despite no longer operating as a printer he still maintained Dutch connections on the continent.

Scoloker seems to have died in 1593, an ‘Anthony Skolykers’ being mentioned in the burial registers of St Mary-le-Strand as being buried on 13th May 1593. The same register mentions several others who were likely part of Scoloker’s household though not all of their relations to him are perfectly clear. He was predeceased by individuals who could have been his children: one Judith Scoloker (possibly a daughter) buried 5th September 1563, and an ‘Anthony Scollinger sonne of Anthonie’ buried 12th May 1674. A servant of a ‘Jone Scollenger’ was buried only a few weeks later on 31st May 1574, perhaps giving a name to another member of the household though it is unclear as to who. A ‘Mistres Scoliker’ survived Anthony and was buried 21st August 1599. Following his death, Scoloker has previously been identified by scholars as the author of the burlesque Daiphantus, or the Passions of Love (1604).11 However, two references to Shakespeare’s Hamlet (composed between 1599 and 1601) which was written after Scoloker’s death, suggest a different author with Albert Pollard in his entry for Scoloker in the Dictionary of National Biography putting forward the idea of a relative of the same name as the printer being the true author of Daiphantus.12 Alternatively, given that the author’s name is simply written as ‘An. Sc.’ there may be no connection to Scoloker at all and modern attributions of Daiphantus to him in recent publications are simply repeating a scholarly mistake from 1807.

The London imprint of Scoloker’s translation of Sachs has an additional publisher, one William Seres (died c.1579) who was a Protestant printer known to have collaborated with several famous partners including John Day (c.1522-1584) who was most famous for publishing John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (1563). Seres specialised in the printing of religious works making him the ideal partner for Scoloker to print Sachs’s dialogue in London and they would collaborate on several works in 1548. Though Scoloker moved within a circle of notable Protestant printers that worked during the short rule of Edward VI (reigned 1547-1553), he seems to have operated only briefly and on the periphery of this group who sought to flood England with pro-Reformation materials.

Indeed, the Henrician restrictions on printing had been relaxed in November 1547 and those in favour of a more radical Reformation of the English Church took advantage of that fact to print swathes of both continental and domestically produced Protestant tracts. The generally pro-Reformation nature of Edward VI’s government meant that these materials could be officially produced and distributed alongside the changes to English religious practices that were rolled out in the Church of England. 1548 in particular saw a wave of Lutheran works translated into English including works such as Luther’s The chief and principal articles of the Christian Faith, Melanchthon’s The Confessions of Faith, and Osiander’s Conjectures of the end of the world. Zwingli, Bullinger, and Calvin also saw an array of their works published in English as, of course, did Hans Sachs.

These works proved popular, and men like William Seres were keen to get them into general circulation. Indeed, Scoloker’s Ipswich printing of the first disputation must have been popular enough to warrant him reprinting it in London later that same year. However, Sachs did not enjoy the great popularity in England that the meistersinger had experienced in his home city, despite many figures of the English Reformation such as Thomas Cranmer having spent time in Nuremberg. Scoloker’s extant translation of Sachs’s work therefore remains as one of the few dialogues by the meistersinger to gain some level of traction in England, despite Scoloker not necessarily having worked with the original.

Scoloker’s translation of Sachs’s dialogue was seemingly based on the Dutch edition rather than the original German. The similarities between the English and Dutch texts certainly suggest that Scoloker translated his English version solely from the Dutch copy he had access to. He even imitated the layout of the Dutch translation by indicating speakers on separate lines, though went somewhat further in his dramatization of the text by adding a cue for the opening speech. Like his Dutch predecessor, Scoloker seems to have translated Bible passages out of the work he was translating from, rather than copying them from any vernacular English version of the Bible. He also begins in a formal form of address but, in contrast to the original German and Dutch, later switches to the informal creating a more disrespectful tone. Scoloker also diverges from previous versions by creating additional domestic servants for the lead characters of his dialogue to interact instead of the female cook and servant boy of the original. These comprise a male servant whom the shoemaker initially interacts with instead of the cook, a maidservant named Katheryn who takes over the cook’s role in the rest of the dialogue, and finally a male cook named John who appears near the end of the dialogue in place of the servant boy.

Scoloker makes further minor changes to the text, sometimes to appeal to his English audience, other times due to misunderstandings during translation. However, the fact that Scoloker took the time to translate Sachs’ work and localise it for England, does speak volumes on the Protestant appeal of this dialogue. The themes of the abuses of the Church’s power, the nature of salvation, Christian liberty, and lay access to and interpretation of scripture, so artfully rendered by Sachs, resonated with the supporters of the Reformation whether they were in Nuremberg, Antwerp, Ipswich, London, or beyond.

Footnotes

For full titles and full bibliography, see the part 4 of the introduction

1 See Bubenheimer’s discussion of Lazarus Spengler in the ‘Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen’, Jones / Lähnemann (2022), p. xviii. Secondary literature is cited with the short titles in the bibliography, with the exception of specialist literature for the ‘English Reformation Dialogues’.̛

2 For more on Müntzer, his radical ideologies, and differences with Luther see Drummond (2024).

3 See Lähnemann/Schlotheuber (2024) and Gieseler / Lähnemann / Powell (2023) for the debate surrounding the forced dissolution of convents.

4 Valkema Blouw (1992),pp. 165-181; and pp. 245-272.

5 On the Dutch Reformation print trade see: Heijting (1994), pp.143-161.

6 John Foxe’s 1563 Actes and Monuments mentions it amongst a list of works that had been banned, p. 573 no.40. On the date of the ban see Beare (1958).

7 Steele (1910), pp. 30-31. See entry No. 294 8 July 1546.

8 Freeman (1990), pp. 476-496.

9 For a full account of Scoloker’s changing addresses in London see: Blayney (2013), pp. 646-649.

10 Page (2015), p. 68. Page provides a breakdown of everything Scoloker imported this year on p. 67. Full details of his imports can be found in the London Port Book (online).

11 The first to put this forward, and source of all later errors, was Francis Douce in his Illustrations of Shakespeare and Ancient Manners, Douce (1817), 2.265.

12 Pollard in DNB Vol. 51, pp. 4-5.

4 thoughts on “Hans Sachs in Oxford 1: Historical Context”