A palaeographic analysis of Bodleian Library MS. Germ. e. 5.

by Marlene Schilling

Report on a History of the Book project

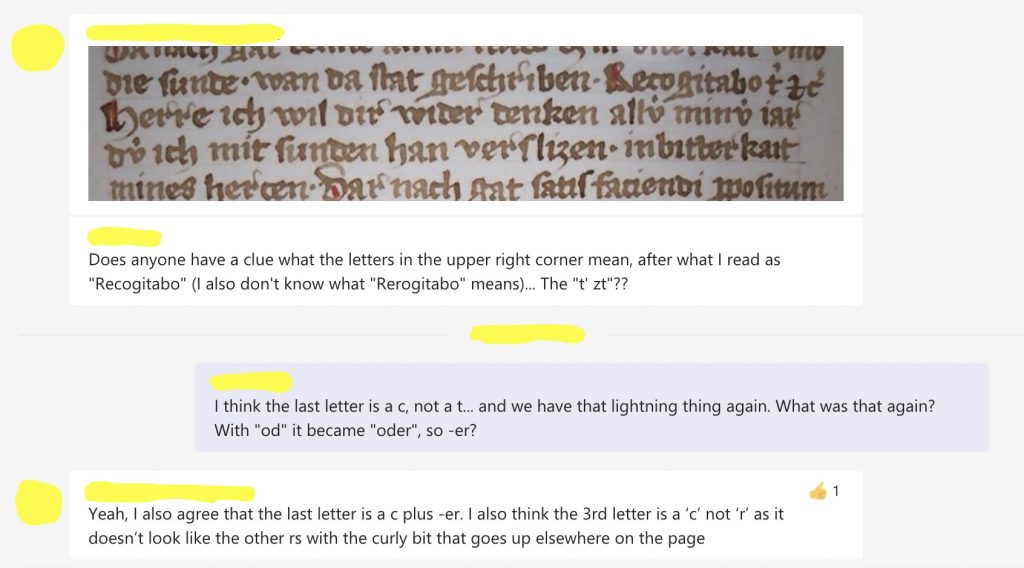

In the academic year 2020/21, six brave Germanists took up the challenge of a special group project: editing and understanding the newly digitised manuscript Bodleian Library MS. Germ. e. 5. (part of the Polonsky Foundation Digitization Project), without the possibility of consulting the manuscript in person. I was one of those students.

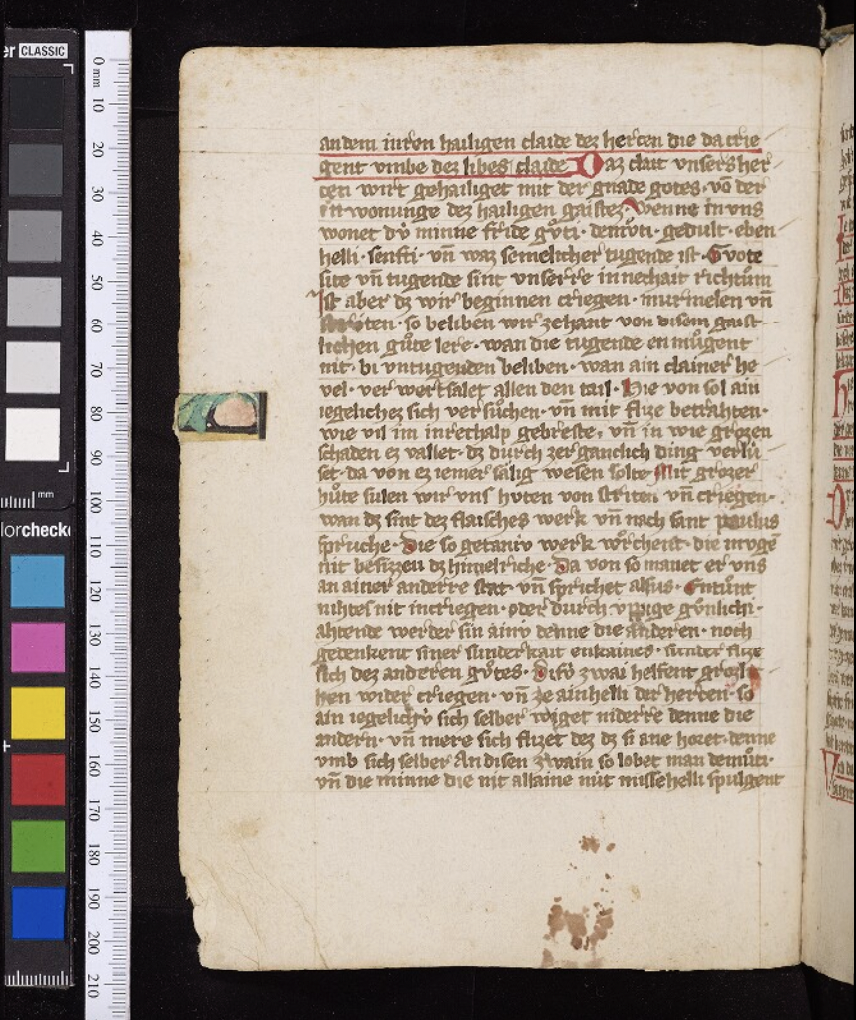

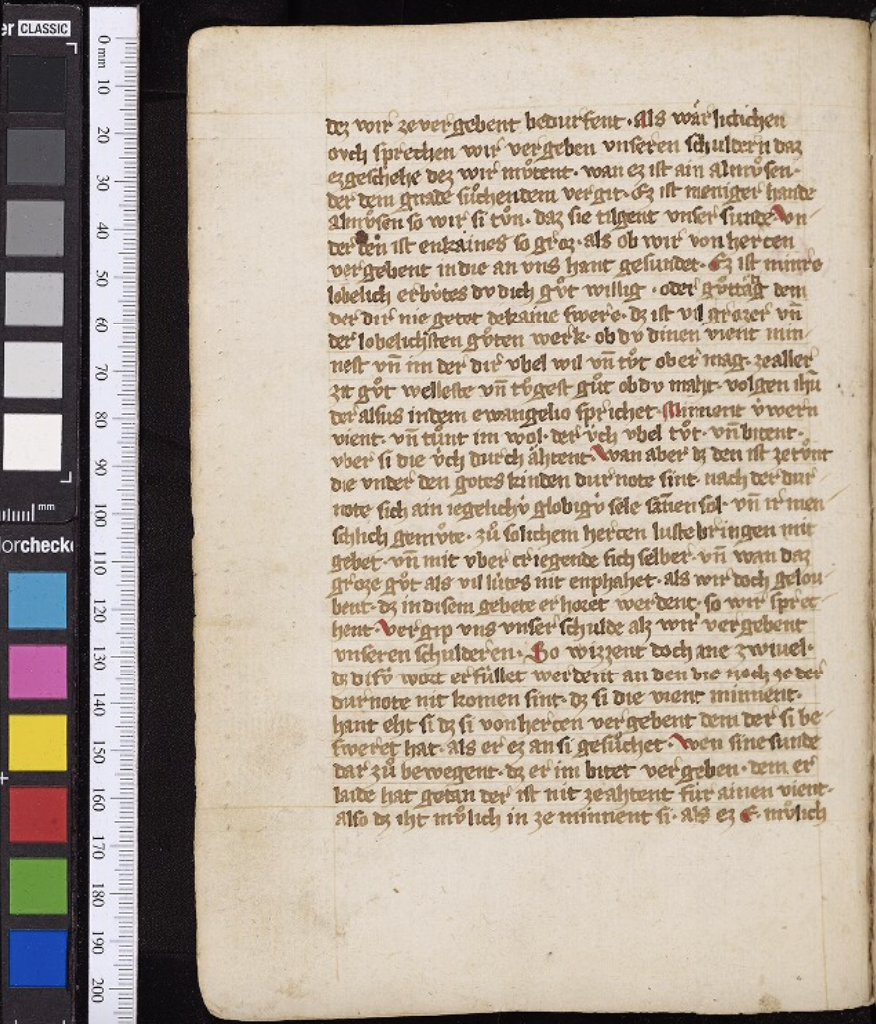

The manuscript is a late 14th century German paper manuscript, consisting of ten religious texts and prayers. In addition to transcribing and encoding five texts for our partial digital edition, each of us looked at a different aspect of the manuscript, such as the dialect or the materiality, to name just two examples. My task was a palaeographic analysis, or in other words, characterising the different “hands” that wrote the manuscript.

Scribal practice

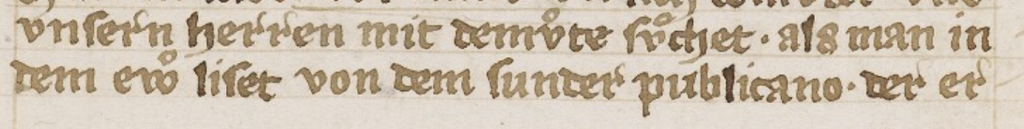

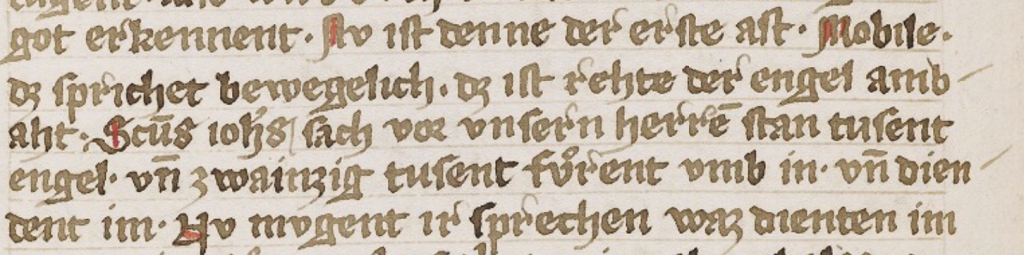

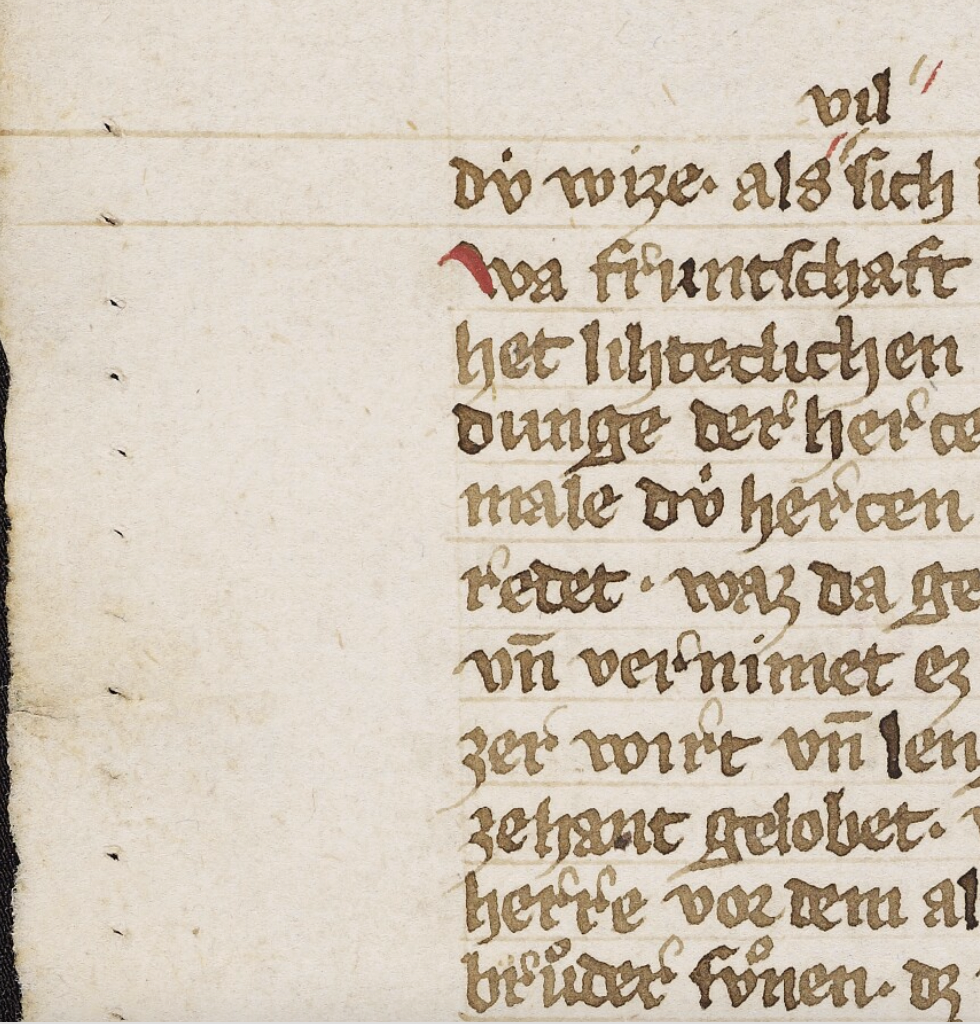

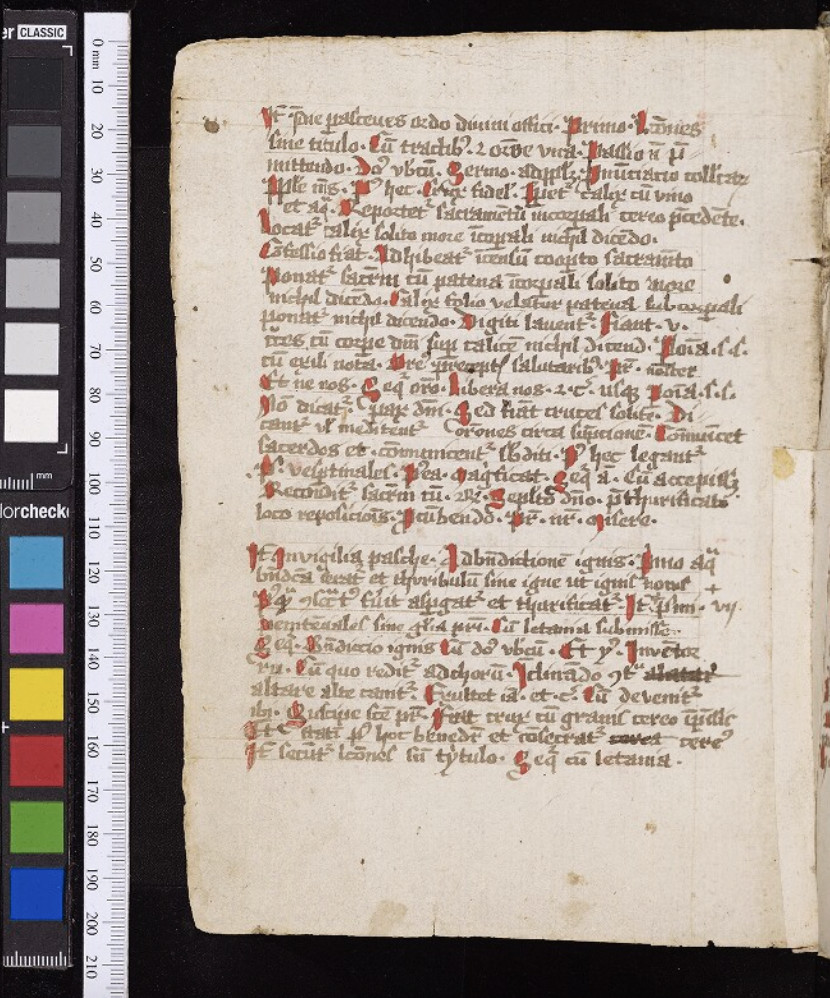

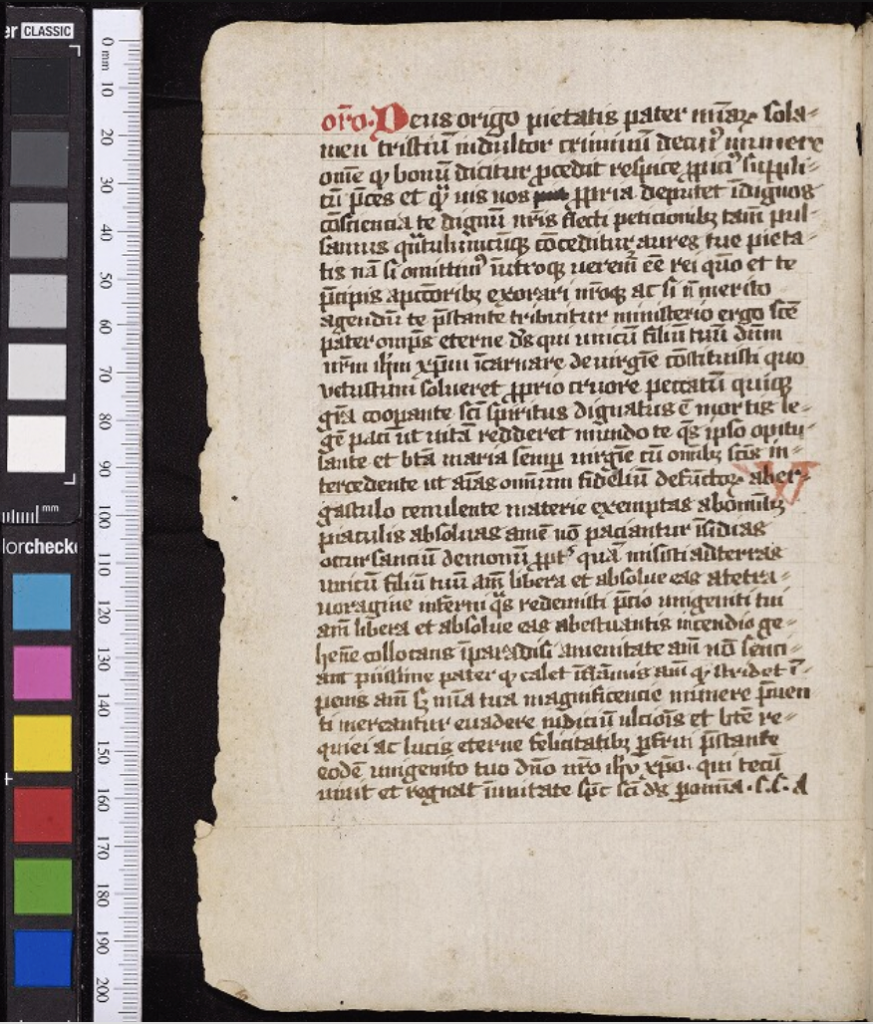

As a first step in my analysis, I examined the script by comparing the characteristics of particularly telling letters. The script used throughout most of the manuscript is the early Gothic Textualis, since it meets all of its central criteria:

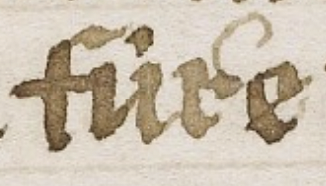

- The a is written as a two-compartment a. This also excludes the possibility of the script used being Bastarda – here the a is one-lobed.

- The ascenders of the letters b, h, k and l do not have loops.

- The long s (ſ) and f do not have descenders, meaning they are standing on the baseline.

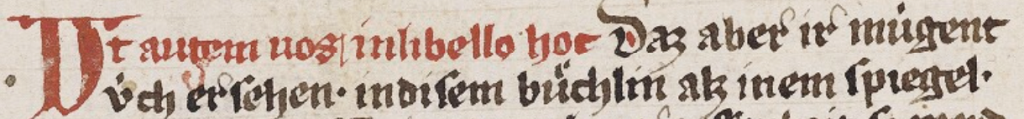

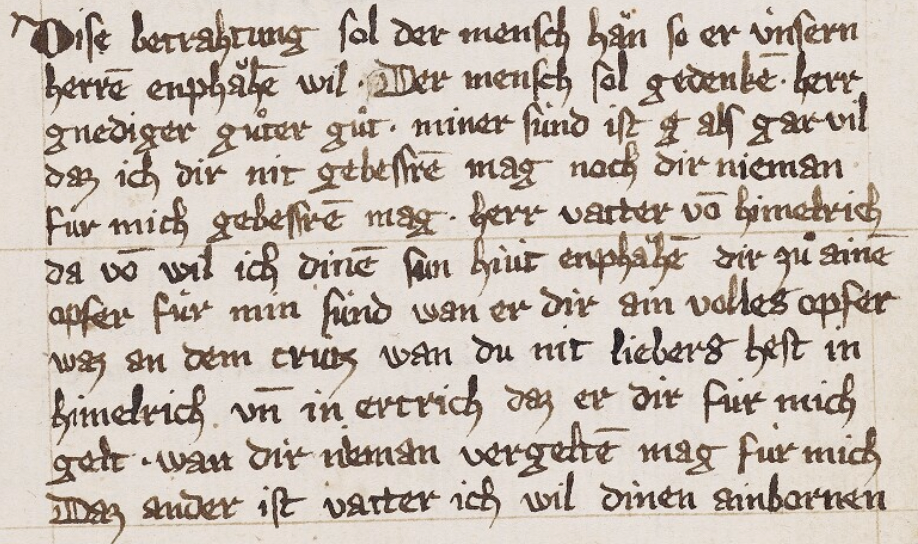

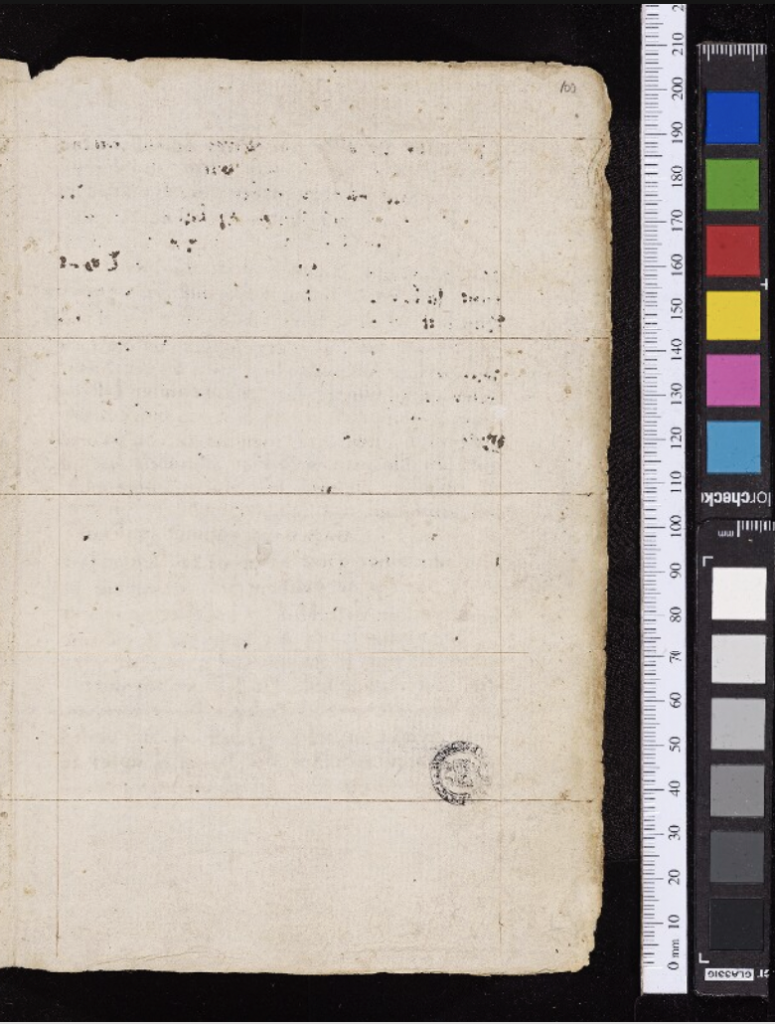

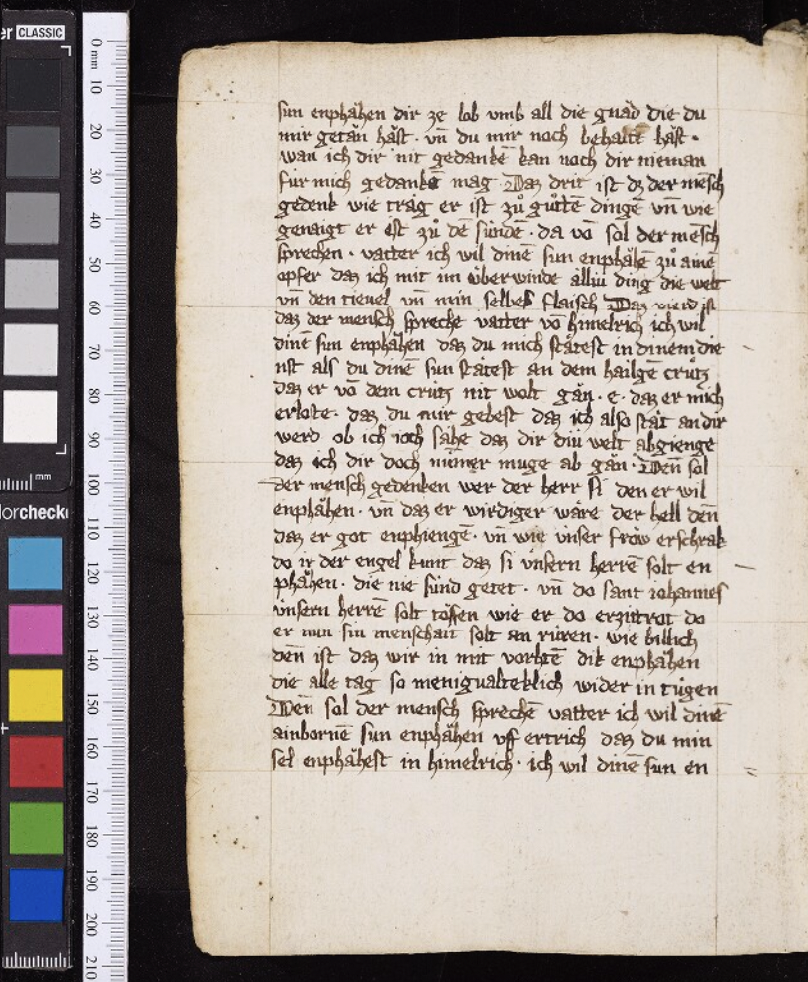

The last six folios are written in a far more cursive script in comparison to the earlier parts of the manuscript, which allowed a quicker writing process. With cursive scripts, the pen-strokes are more fluent and there are less strokes necessary to form a letter. However, this also creates the impression of a more informal and less neat text appearance.

Layout

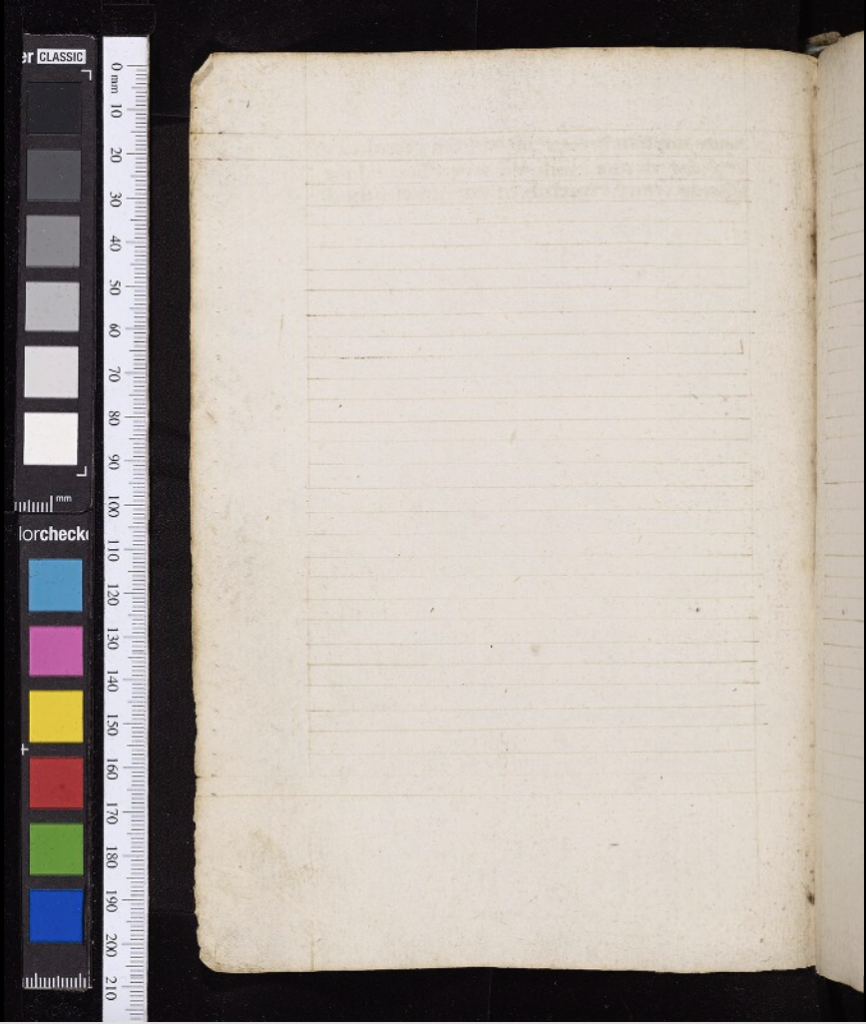

The layout of the manuscript is fairly consistent: Each page is divided into one text block marked by a frame of two horizontal and two vertical lines, with margins on all four sides. The text-space is ruled to form 30 lines, with pricking indicating the positions. The layout was done before the actual writing process as preparation, with empty pages showing the steps taken.

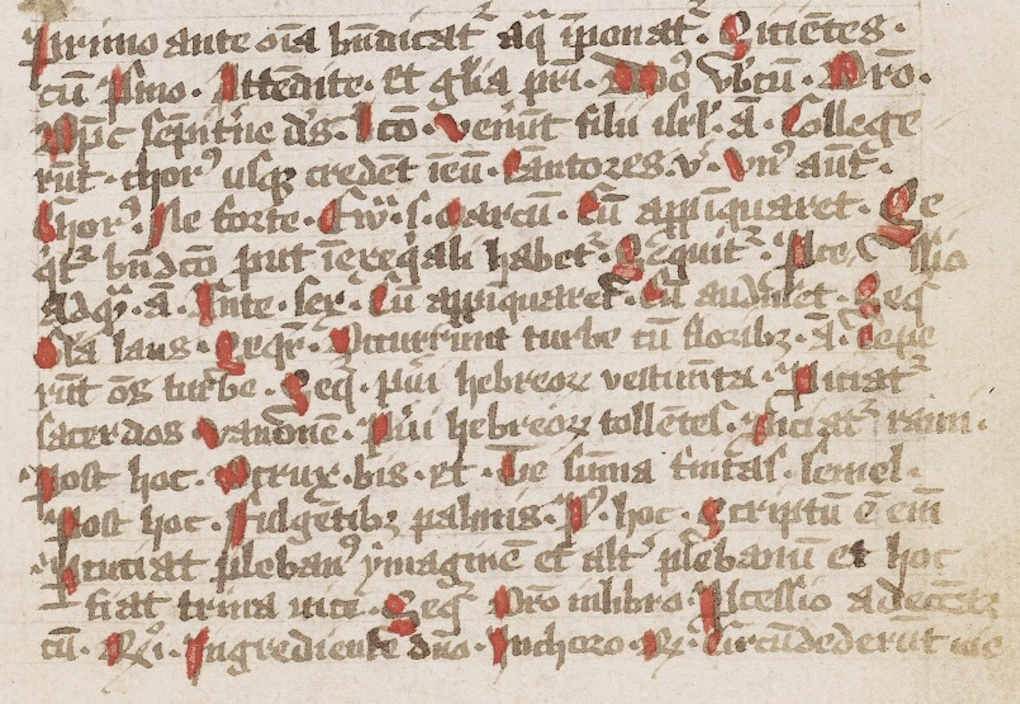

The last folios of the manuscript again show different characteristics, since they have a different layout: There are still the four lines dividing a text-space from the margins, laid out like the rest of the manuscript, but the 30 pre-drawn lines are missing. Here the writing space is divided into four equally sized blocks by three additional horizontal lines.

Two different forms of spelling

In the manuscript the scribe differentiates between ſ (long s) and s (short s). The usage of these different s-forms is linked to their position within a word: Short s is used in the final position and for capital letters, long ſ in all other instances.

The letters u and v are also used interchangeable, with no phonetic difference.

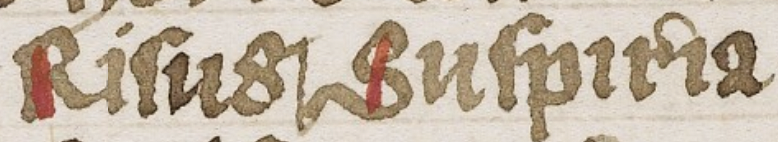

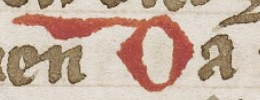

Capital letters

The spelling of uppercase and lowercase letters is not standardized in the manuscript. In most texts, the capital letters are highlighted in red. They have a mainly structuring purpose, like marking the beginning of a new paragraph. In rare cases they are also used to highlight a key word, mainly Latin terminology.

On the last six folios, capital letters are not highlighted in red, but with additional black ink decorative pen-strokes. They mainly mark the beginning of new paragraphs.

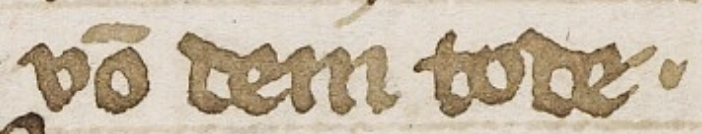

Diacritics

There are three main diacritics used in the manuscript:

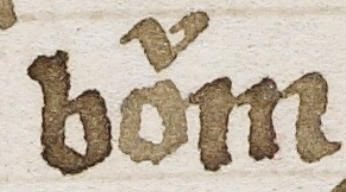

- Superscripted o: It appears with the u-sounds (v/u) forming the diphthong ‘v/uo’.

- The superscripted dot also appears with the u-sounds (v/u) forming the phonetic umlaut ‘ü/ue’.

- Superscript v: There are two possible functions for that diacritic. (1) It could be used to form the diphthong ‘ov/u’ in combination with the letter o. (2) It could be used as an indication of pronunciation with the letter a, marking the phonetic difference between a long a and a short a.

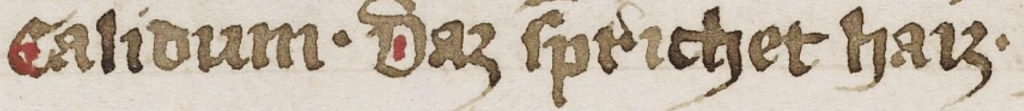

Punctuation

The main punctuation mark used in the manuscript is a punctus elevatus, which is used both as a comma and as a full stop. Therefore the respective usage in each case must be determined by the context, something we did for the normalised version of our texts in the digital edition. A new sentence is not necessarily highlighted by following a punctus elevatus, there are several examples where only a capital letter indicates the start of a new sentence.

Decorations and highlighting

The manuscript’s texts all have different forms of rather modest highlighting. It serves primarily a structuring purpose instead of a mere decorative one. The most used decoration are delicate red pen-strokes to highlight some of the initial letters. The second text uses this form the most: Here more or less every third word is highlighted in red.

In addition to these smaller red highlights, the first text presents original Latin phrases, which are then translated in the following, as written in red ink.

The forth and the fifth texts also include fully rubricated red initials, more or less only in relation to capital letters. Here the ‘simpler highlights’ are mostly used to mark Latin terms, the accompanying German translation as well as key words.

There are no red highlights in the last six folios of the manuscript, which are only written in dark ink.

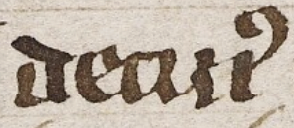

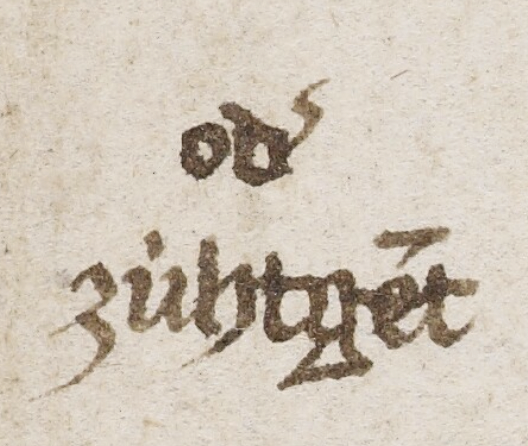

Abbreviations

Numerous abbreviations can be found in the manuscript both with or without an abbreviation mark, which were used to quicken and facilitate the writing process. Most abbreviation marks are Latin abbreviations, but are also applied on German words. The three main Latin abbreviation are the following:

- A bar above a letter indicates at least one missing letter, often an missing nasal.

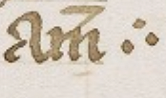

- The elevated ‘nine’-symbol indicates a missing us-suffix.

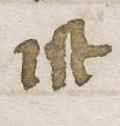

- A small elevated lightning-symbol indicates a missing er-suffix. This is especially used in the marginalia to maximize this even more limited space.

Hand

One of the bigger challenges of a palaeographic analysis is differentiating the different hands used in the manuscript. Different characteristics of key letters need to be carefully evaluated and analysed. These key letters however can vary from manuscript to manuscript. In the case of MS. Germ. e. 5. the letters included a, g, h and r, the normal r with a decorative hook as well as the round r of the ligature or. The online catalogue entry for MS. Germ. e. 5. identifies three different hands. However, after a careful analysis of more or less every folio of the manuscript I came to the conclusion, that there are actually four different hands in the running texts (even more in marginalia):

- The main hand of the manuscript is hand 1 (fols. 1r-7r, 9r-99r).

- Folios 7r-8r are written in hand 2 (fols. 7r-8r).

- The catalogue entry identifies hand 1 as the hand for folio 99v. However, this hand actually differs from hand 1, therefore I identified it as an additional hand, calling it hand 3 (fol. 99v).

- Hand 4 (fols. 100r-104v) can be identified for the last folios of the manuscript. Since it is a more cursive script it differs significantly from the first three hands.

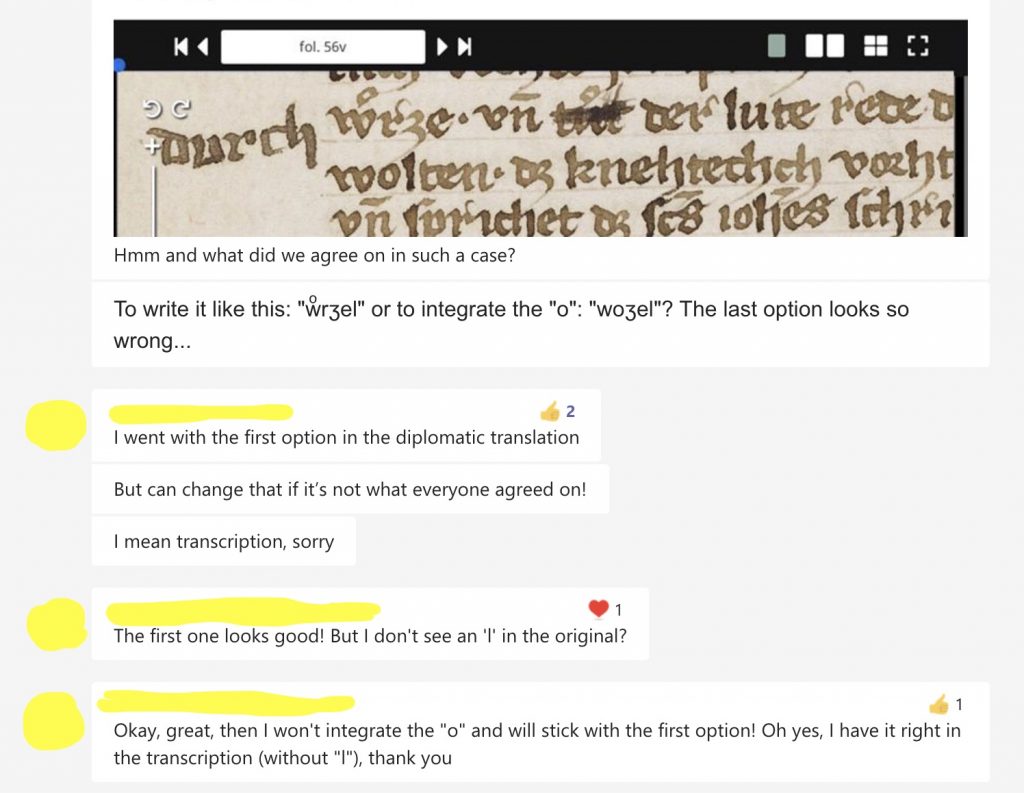

Working on a manuscript in times of lockdown

This palaeographic analysis was made without ever consulting the physical object in person, since the situation in Hilary term 2021 simply did not allow it. I relied completely on the digital images of the manuscript on the Digital Bodleian Website. And on a practical note: The functions of these images really facilitated my analysis, since they allowed an easier in-depth analysis of the texts’ characteristics. Key functions include zooming ‘into the manuscript’ or putting different folios side by side for a clearer, more telling comparison, which I found especially useful for identifying the different hands. It also made the communication within our group easier: Whenever there was a phenomenon or a word within the manuscript that we did not understand or simply could not decipher, we sent a quick message in our Microsoft Teams Chat with an attached screenshot from the digitized facsimile and just waited for the other’s expertise. And like that, we solved every mystery as a team ;)!

My experiences confirmed how important it is to digitize manuscripts in order to make them accessible (although I have to say: nothing ever comes close to seeing a manuscript in person for the first time) – not only in times of closed libraries, but also for scholars all around the globe, who might not be able to easily consult a specific manuscript, that is otherwise crucial to their research, without the digital facsimiles. Digitizing manuscripts certainly saved me, my analysis and my essay in this crazy year!

***

Marlene Schilling just finished her MSt in Modern Languages (German) at the University of Oxford in the academic year 2020/21. For her Method Option she took Prof. Henrike Lähnemann’s History of the Books course.

Featured Manuscript

Bodleian Library Oxford MS. Germ. e. 5.

Bibliography

MS. Germ. e. 5 in A catalogue of Western manuscripts at the Bodleian Libraries and selected Oxford colleges (Accessed 18.06.2021).

University of Nottingham (no date), Manuscripts and Special collection, Laying out the text (Accessed 18.06.2021).

Brown, Michelle P.: A Guide to Western Historical Scripts from Antiquity to 1600. London 1990.

Derolez, Albert: Palaeography of Gothic manuscript books. From the Twelfth to the Early Sixteenth Century. Cambridge 2003.

Parkes, M. B.: Pause and effect. An Introduction to the History of Punctuation in the West. Berkeley/Los Angeles 1993.

Schneider, Karin: Paläographie Und Handschriftenkunde Für Germanisten : Eine Einführung. Dritte, Durchgesehene Auflage [Sammlung Kurzer Grammatiken Germanischer Dialekte. B. Ergänzungsreihe Nr. 8]. Berlin/Boston, 2014.

Image Permission

Digital Bodleian (images from Bodleian Library MS. Germ. e. 5: Creative Commons non-commercial license, with attribution (CC-BY-NC 4.0)). Images © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford 2020.

1 thought on “Hands, ink and abbreviations”