Increasing Awareness of the Bestiary in Merton College Library, MS 249

Sebastian Dows-Miller

The bestiary genre is well known, both inside and outside of scholarship, for a very simple reason: its images. We are fascinated by the insights that these give into a different kind of scientific understanding, and the minds of the illuminators that created them.

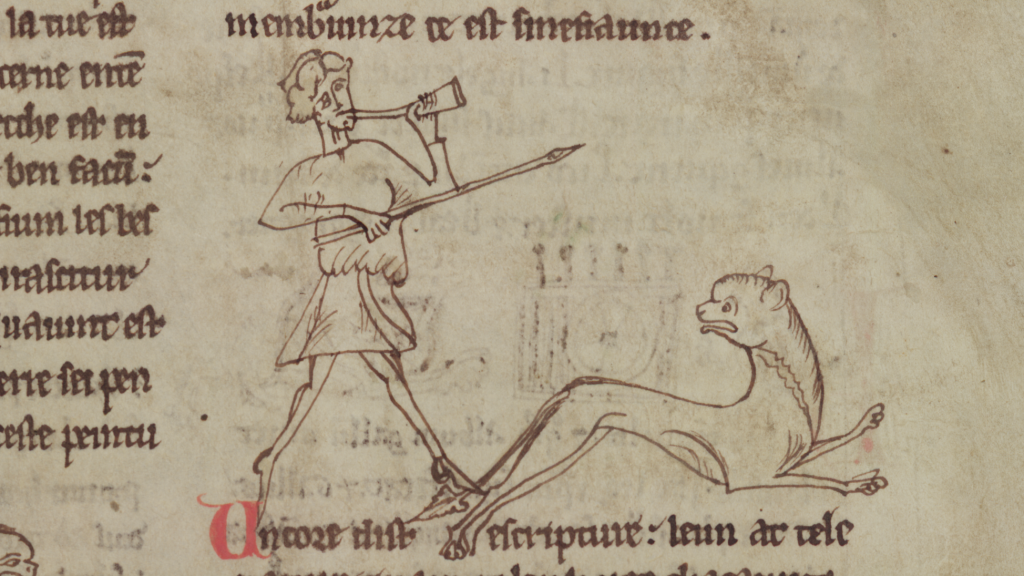

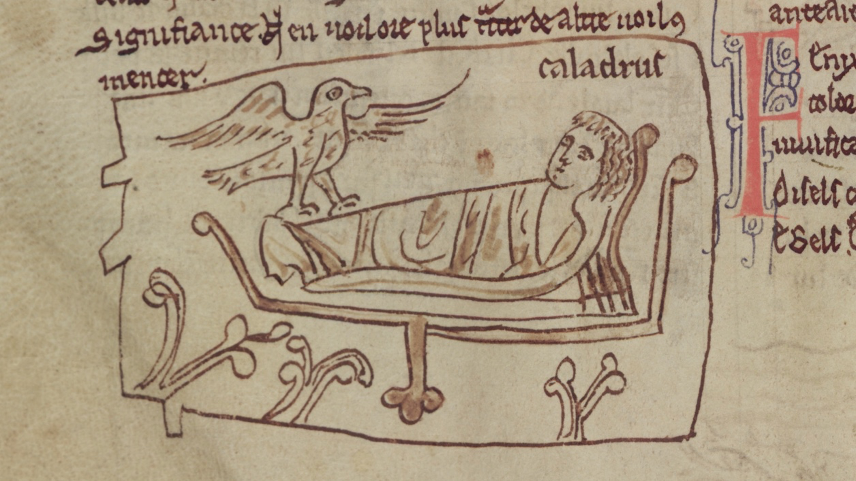

Oxford, Merton College Library, MS 249, a mostly thirteenth-century miscellany, which contains a copy of the animal sections of Phillipe de Thaon’s twelfth-century Bestiary, is hardly the most lavish such witness in existence; its illuminations (of which there are 46 depicting animals or people) are rudimentary line drawings, largely unframed, with very minimal use of colour.

The two other surviving manuscripts containing the text are, or would have been, much more ornate. Copenhagen, Kongelige biblioteket, GKS 3466 8°, for example, contains wonderfully vivid illuminations in a broad range of colours which, while not always very zoologically accurate (even for the non-mythical beasts!), are evidently the work of a talented individual.

London, British Library, Cotton MS Nero A V, meanwhile, was seemingly never completed, but the presence of some detailed, preliminary pencil sketches (see e.g. f. 42r and f. 62v), and the complex mise-en-page (see e.g. f. 43v), suggests that it would have looked much like KB GKS 3466 8°.

Both manuscripts are smaller in size than Merton College’s, and the text block consists of a single column as opposed to the two in Merton 249. They also make less sparing use of their available space, sticking to one line of verse per line of text in the Anglo-Norman sections, while Merton 249 concatenates lines one after the other, in an apparent attempt by the scribe to conserve parchment.

In a way it is this simplicity, presumably born of necessity, that makes Merton 249 an ideal tool for increasing public awareness of the medieval bestiary within manuscript culture, particularly in our age of lockdowns. How many crudely drawn images of lions, unicorns and other fantastic beasts must have arisen from home-schooling sessions in recent months? These drawings may not look much like the real thing, but they represent the artist’s idea of the animal represented, and thus give us a much greater insight into their world.

This is precisely why Merton 249 has much more to offer the public than has previously been acknowledged. Much like visiting a parish church as opposed to a cathedral, reading Merton 249’s Bestiary is somehow more personal, and — ironically in this book of beasts — more human.

How, then, to help Merton 249 burst back, almost like the phoenix on f. 8v, into greater public awareness? The answer to this, I believe, is twofold, and this has formed the basis of my project for the History of the Book course.

There have been a number of editions of Philipe de Thaon’s Bestiary in recent years,[1] but no truly digital editions, written in XML to allow parallel reading of the digital facsimile, transcription, and translation alongside detailed analyses of the text. This is a balance I wish to redress for Merton 249, since a bestiary, perhaps above all other medieval texts, lends itself to such a process of edition, allowing the text to be experienced almost as it is in the flesh, with image alongside text, in a way bested only by visiting the manuscript in person. This edition will provide a valuable resource for scholars wishing to consult the manuscript, as well as allowing those with a passing interest in it to experience the Bestiary for themselves.

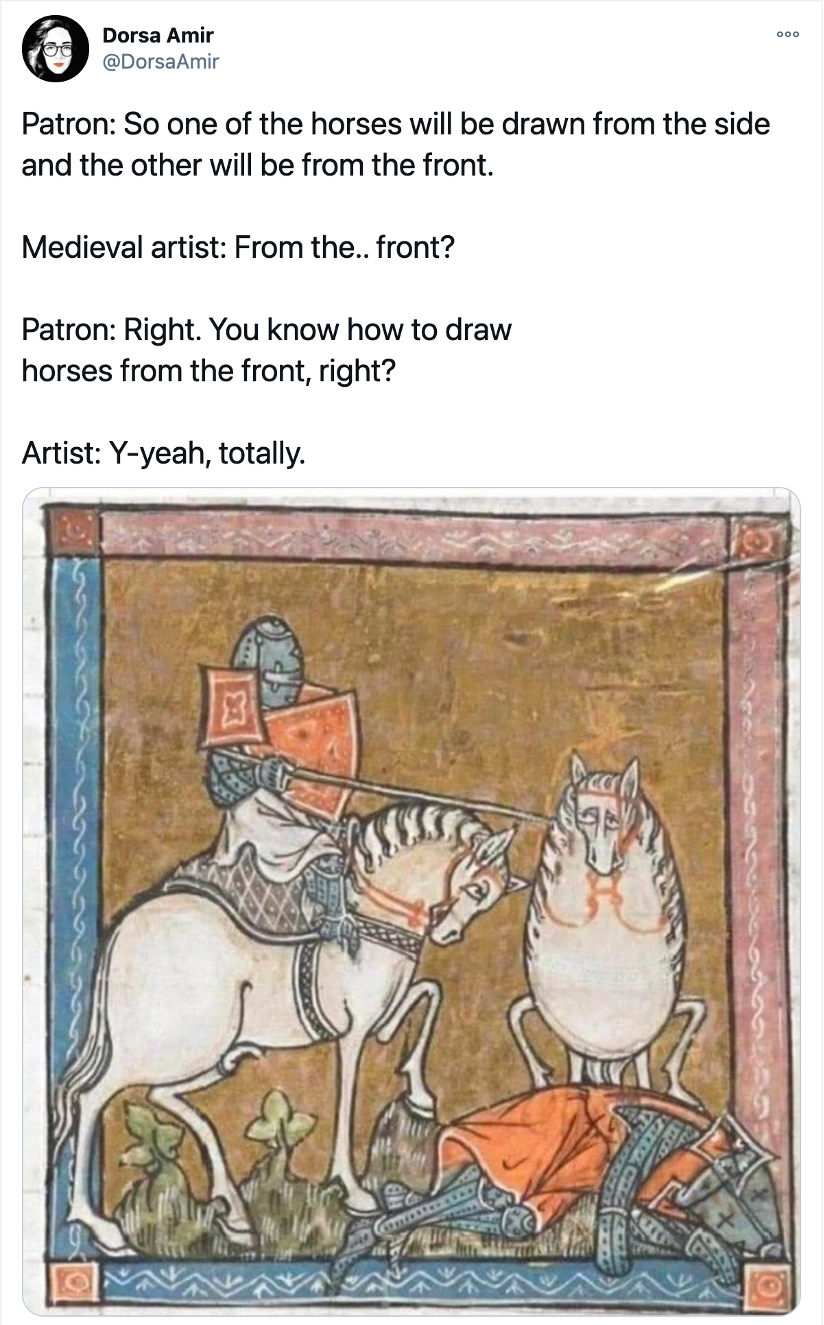

While the appeal of a digital edition to the public at large may be limited, there is no shortage of interest in medieval illuminations. In November 2020 one image, from London, British Library, Add. 10292, f. 213r, proved particularly entertaining for a modern audience in its depiction of a horse from the front. So popular was the image that it gained its tweeter, Dr Dorsa Amir of Boston College, over 5000 retweets.

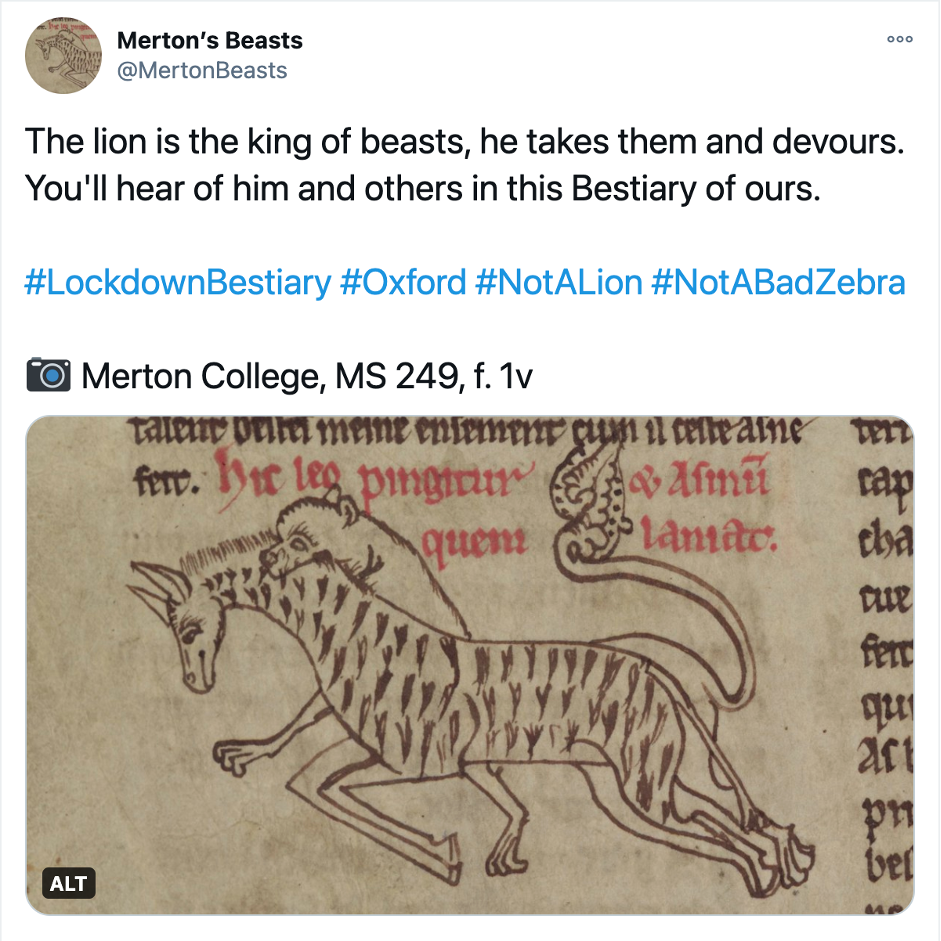

During the first national lockdown in spring 2020, Dr Kathryn Murphy (Oriel College, Oxford) and Prof Katherine Ibbett (Trinity College, Oxford) began a #LockdownBestiary project, which has expanded awareness of medieval bestiaries beyond medieval scholars, and it is this spirit which I am attempting to revive as we find ourselves in Lockdown 3.

Through regular tweets on the Twitter account @MertonBeasts, I am hoping to attract new audiences to this particular manuscript witness, and to the text more broadly, so that academics and non-academics alike will be drawn to read the text itself through the digital edition, once it is available.

By making the text more accessible, I also hope to encourage a broad range of readers to engage with its darker side. Not unusually for a twelfth-century text with a heavily Christian flavour, there are numerous diatribes directed at Jews, ‘pagans’, and women, which form an uncomfortable – and yet integral – part of the text.

That we may so greatly enjoy the illuminations and descriptions within this manuscript, and yet be troubled by many of its other themes, is indicative of a tension between our accepted cultural norms and those of the past, which has come to be as familiar to the general public as it is to historians. Such a tension is arguably manageable, even healthy, since it reminds us that we can appreciate medieval art and material culture without condoning views we recognise as incompatible with our values, and it has an essential role to play in informing our relationship with the past.

This medieval bestiary is a fantastical, material, troubling object, and it is only by addressing each of these characteristics, fully and in turn, that we are truly able to engage with it.

[1] The most recent edition is Philippe de Thaon. 2018. Bestiaire (MS BL Cotton Nero A. V), ed. by Ian Short (Oxford: Anglo-Norman Text Society).

Sebastian Dows-Miller is an MSt candidate at Merton College, Oxford. He has a particular interest in text transmission within manuscript culture, as well as short texts written in Old French, and is always very pleased when the two intersect. Follow him on Twitter here, or follow Merton Beasts directly.

This post is an adapted version of one that originally appeared on the Teaching the Codex blog. The author wishes to thank Dr Mary Boyle and Dr Tristan Franklinos for their helpful suggestions on the original post.

1 thought on “Reawakening Merton’s Beasts”